CHAPTER ELEVEN

THE SOLE SUPERPOWER

THE 80s AND 90s: A TIME OF COMEBACK

The next two decades will be some of the best times for America in its four-century history. By and large the political squabbling between the Democrats and Republicans will settle down, despite a very brief but most unsuccessful effort of the Democrats to use the impeachment weapon against the Republican President Ronald Reagan in the mid-1980s, and a similarly unsuccessful effort of the Republicans to do the same against the Democrat President Bill Clinton at the end of the 1990s. Other than those two ill-advised political ventures, national politics will be quite peaceful during those two decades.

In the realm of foreign diplomacy, this will be a time of true greatness for America, the Cold War coming to an end, with China deciding to take up pro-Western economic ways, and the Russians attempting also to take a more West-like approach to their own politics. Both developments will actually make for quite pleasant East-West relations. There will be ugly political events abroad, which will always be the case. But in general, America will stay out of these matters, except on a few occasions when America was looked to, as – at that point – the world’s only superpower, to referee some of these painful events. And yes, there will be attacks on America, even at home as well as abroad. But the American response to them will be measured and thus quite well-respected globally.

Domestically, the economy will flourish greatly. And the government will be able not only to balance its budget but even to reduce the federal deficit a bit. Such wise government spending will take place in the later 1990s thanks to a strong Republican Congress under Newt Gingrich, and a Democrat presidency under Clinton, Clinton himself quite willing to go down the same economic path. Domestically, socially speaking, this will also be a time of relative tranquility.

Unfortunately, there will be tragic events that will take place in those years, but as individual incidents, and not as part of any kind of broader political trend. And the national crime rate will continue to be disturbingly high, a lot of it because younger and older Americans will have quite conflicting views on the matter of marijuana and recreational drug use. And changing social circumstances for Blacks will undermine some of the social disciplines needed to support local peace and social stability.

However, American society will, in general, present itself as an inviting social enterprise, women taking more active roles in the nation’s economy and politics, and numerous Blacks now moving into that realm. And Middle America, based on a very strong locally-based family system, will also continue to occupy a place of honor in the general scheme of things.

And Christianity will seem to experience a bit of a spiritual revival, particularly in the form of the popular evangelical preaching presented on the nation’s televisions, although there will be those voices (as always) critical of such a social-moral development. And some mishaps along the way will play into the hands of the critics. But in general, things will settle down into a more familiar moral-spiritual pattern for American society and culture.

In short, America will find itself prospering greatly on a number of fronts during those two decades.

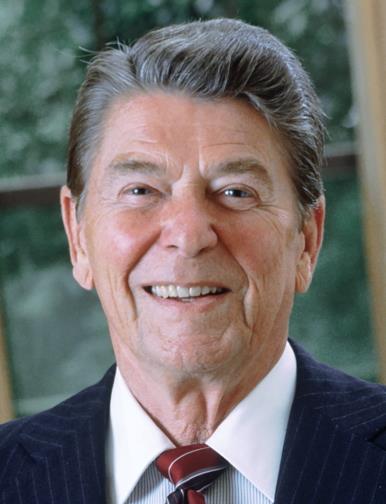

RONALD REAGAN

Reagan the man

Reagan, in so many ways, summed up Middle America’s idea of success. He entered adulthood as a strong Christian (though mostly privately so), starred in his first Hollywood movie Knute Rockne in 1940, and because of poor eyesight was activated from the Reserves only into the army’s Public Relations operations during World War Two. Then after the war he became a strong Democrat, combining his ongoing movie career with his interest in political fairness, serving as president of the Screen Actors Guild (1947-1952), during some of the toughest times for Hollywood when America was experiencing an intense Communist scare.

Reagan, in so many ways, summed up Middle America’s idea of success. He entered adulthood as a strong Christian (though mostly privately so), starred in his first Hollywood movie Knute Rockne in 1940, and because of poor eyesight was activated from the Reserves only into the army’s Public Relations operations during World War Two. Then after the war he became a strong Democrat, combining his ongoing movie career with his interest in political fairness, serving as president of the Screen Actors Guild (1947-1952), during some of the toughest times for Hollywood when America was experiencing an intense Communist scare.

But gradually his interest in the world of politics pulled him over in the direction of the Republican Party, as he became a strong Eisenhower and Nixon supporter. Then in 1964 he was called on to address the Republican National Convention (which nominated the quite Conservative Barry Goldwater as its presidential candidate that year), which led the California Republican Party to ask him to run as governor in 1966 against the two-term Democrat incumbent Pat Brown. Winning that race, as California governor he was careful to restrict excessive government spending, pleasing the California electorate enough to re-elect him four years later in 1970.

As his second term came to a close, he began preparations to run for the U.S. presidency, although the Republicans ultimately chose Ford to run for them in the 1976 race. Reagan would try again four years later in 1980, except this time he would not only gain the Republican nomination, he would win the U.S. presidency.

Reagan as a “tough” president

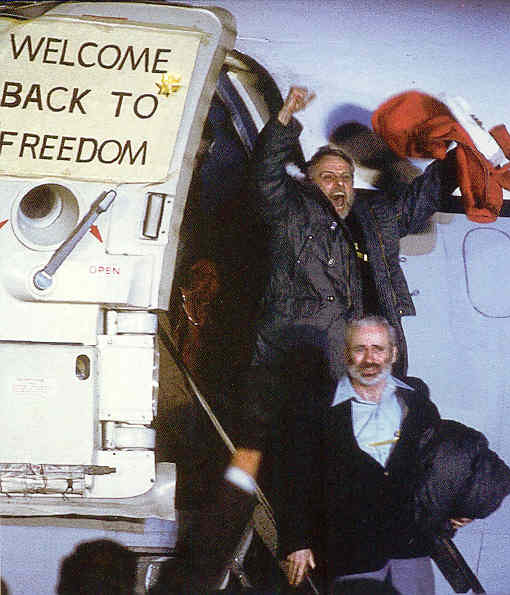

Most interesting, symbolizing a new era in American political life, the very day that he was sworn in as president, the Iranians finally released the American embassy hostages they had been holding for well over a year, although actually it was Carter that had negotiated the release. But visual credit would play most positively to the new Reagan presidency, people finding it easy to believe that the Iranians were rather nervous about having to deal with Reagan over the matter.

Reagan’s near assassination. A “tough” Reagan would also quickly present itself to the American public, and the world, when, in March of his first months in office, a crazed assassin shot and wounded both Reagan and his press secretary James Brady. Reagan would come back quickly from a punctured lung, though Brady would remain permanently paralyzed. Most interestingly, this event increased Reagan’s national popularity rating greatly, to nearly 75%.

The air traffic controllers strike. And the public would stand strongly with him when he mobilized the military to take over air traffic control when in August of that same year (1981) the national air traffic controllers union went on strike, attempting to shut down air travel in order to negotiate a stronger labor contract. The union was humiliated, air traffic continued, though reduced in volume until the 11,000 fired air traffic controllers could be replaced. And the nation stood strongly with Reagan in the matter. Lesson learned: do not mess with American national security with Reagan in the White House!

Grenada. In the realm of foreign affairs, Reagan showed this same toughness, although it was accompanied by a very wise sense of political calculation. In October of 1983 Reagan sent American troops to intervene in political developments in the tiny Caribbean Island of Grenada, when Marxists conducted a military coup to take over the island. Reagan did so because Grenada lay most strategically along the naval route leading to the Panama Canal, and Reagan did not want to see any further loss to America of its position in the region. But he did so also with the strong support of the leaders of other islands in the region. But broader world opinion stood against Reagan, when the U.N. General Assembly protested strongly against Reagan’s move. But Reagan proved to be so unmoved by “world public opinion” that the world found good cause to get over its feelings quickly on the matter.

Lebanon. But Reagan could also be cautious, when caution was required. When a horrible civil war broke out in Lebanon, the U.N. in June of 1982 asked for support in sending a peacekeeping force to separate the various Muslim-Christian factions going at each other. Reagan responded by sending 800 American troops to be part of that U.N. force, which included French and Italian troops. But the situation was so complicated by the fact that the Lebanese factions were scattered broadly around the country, so that there was really no way to separate them from each other, even by military intervention. And then Syria jumped into the matter, making things even more complicated. Thus the peacekeeping forces found themselves mostly posted to their own barracks. Then in October of 1983, a well-planned bomb attack on the U.N. barracks killed 241 American and 58 French soldiers.

Thus the U.N. intervention was proving to Reagan to be merely pointless and dangerous. Consequently, by February of the following year (1984) Reagan acknowledged American involvement to be a sad mistake and pulled the American troops out of the operation. But America saw this retreat not as failure, but as great wisdom on the part of a president willing to take his losses in order to prevent an even greater catastrophe, something not seen often on the part of those in power.

Ongoing economic problems on the domestic front

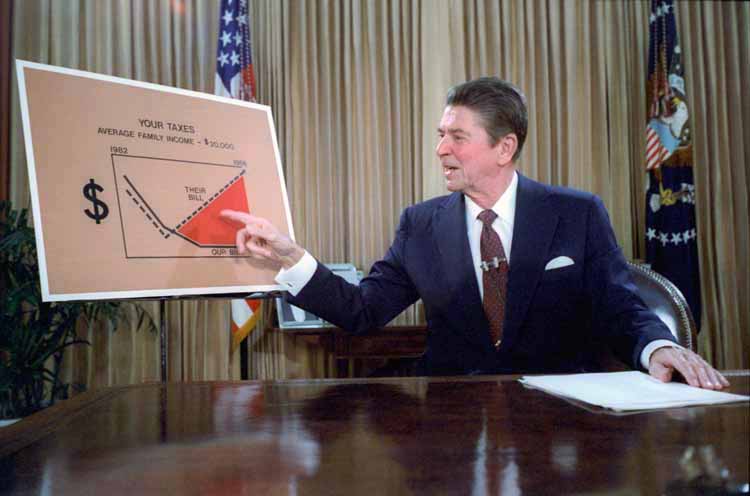

A sad economy. Reagan campaigned strongly about the state of the economy, and the need for what soon came to be popularly termed “Reaganomics,” or in classic economic terms, supply-side economics. The idea was simply that to bring down inflation, production needed to be increased, lowering the price of each item being offered on the market. But how was production actually to be increased? With Volcker’s high-interest-rate strategy and with very high energy costs, how was production supposed to take off on its own?

The answer came in two forms. First of all, Congress was tiring of the financial game that Volcker was playing and threatened to take away some of the authority of his Federal Reserve banking system if he did not lower the discount (interest) rates. He ultimately had no choice but to back down.

Secondly, the economic recession that hit the world ultimately also hit Russia … although Russia − as a huge oil exporter − should have been enjoying the fruits of the massive energy price rise. But other parts of Russian industry were in deep trouble … inspiring the Russian decision to increase even further its oil exports – by offering its oil at a slightly lower price. But OPEC members were not stupid, and realized that to keep up their own sales, they dared not let Russia undercut them. So they too lowered their prices. Now a price war found itself going on in the energy field as producers lowered their prices ever further to stay in the game. Soon the outrageous cost of energy dropped down to a more normal range. Industrial economies could now take off again.

A rising government debt. But Reagan’s wisdom did not seem to extend to the matter of governmental financing, despite his success in this matter as California governor. Taxes were lowered in order to help pick up the economy. But this merely increased tremendously the federal deficit (the difference between what it spends and what it has by way of its own income), from a trillion dollars at the beginning of his presidency to three times that amount at the end of his presidency eight years later.

Reagan outlines on TV his plan for Tax Reduction Legislation – July 1981

Sadly, to cover that deficit, the government had to borrow from various investors, many of them foreign governments, but also the Social Security Trust Fund. Once again, the connecting of the monies of the Trust Fund with the federal debt was a very bad idea, as all such Ponzi schemes happen to be. People understood this danger, but dismissed it because supposedly the American economy, even in the face of governmental financial mismanagement, was considered to be the soundest economy in the world. At this point, no one was willing to challenge this unquestioned belief that the American economy, the dollar itself, and the financial foundations of the federal government were most unshakeable.

America’s moral-spiritual division deepens

Trying to make prayer “constitutional.” In May of 1982 Reagan, in a speech to Congress proposed an amendment to the constitution, reading:

Nothing in this Constitution shall be construed to prohibit individual or group prayer in public schools or other public institutions. No person shall be required by the United States or by any state to participate in prayer.

In this it was soon revealed that some 80 percent of all Americans supported this amendment. But Secular groups opposed the amendment strongly, and again even the leadership of mainline Christian denominations felt that it was not necessary. Ultimately (1984) it failed to receive the necessary two-thirds vote in the Senate, only 56 supporting the amendment (37 Republicans and 19 Democrats) with 44 opposing (26 Democrats and 18 Republicans). Reagan would try again the next year, with no better luck in the process. So prayer would remain officially forbidden in America’s public schools.

The continuing decline of America’s older Christian denominations. Meanwhile, older Americans continued to maintain their church-going habits over these years. But those of the younger Boomer generation were much less inspired to get involved in such a Christian lifestyle. Consequently, as the older Vet generation aged (and began to die off) so also did church attendance continue to evidence a slow but steady decline.

Sadly, the older Protestant denominations (Methodist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Episcopal, etc.) that had been at the heart of America culture since its founding, attempted to answer the obvious cultural challenge facing them by taking up “peace and social justice” causes and a strong support of feminism − cultural shifts that they hoped would interest the ever-crusading Boomers. It did a little. But ultimately it pulled these denominations away from what constituted their true and well-proven strengths … their deep dedication to the Biblical view of society and its rules and regulations.

Televangelist Jerry Falwell and his teleministry team (the “Moral Majority”) trying to create something of a Hollywood-style “New Awakening”

Tragically, the American church, in order to bring itself “up to date,” thus found itself once again wandering from its original spiritual foundations.

Another very big part of this cultural shift resulted from the deadly AIDS virus which, by the mid-1980s, had spread quickly among practicing homosexuals. Instead of promoting restraint in homosexual activity, it all served the Liberal world as an example of where the older social rules against homosexuality had to be put aside, and more sympathetic hearts needed to see these individuals as victims of a cruel world, the cruelty somehow the fault of those unsupportive of the rights of homosexuals to freely engage in homosexual activities. Even Christian groups now came out in support of the idea that homosexuality and Christianity did not stand in opposition to each other, and that those who held onto Christianity’s long-standing opposition to such practice were themselves most “un-Christian.”

Most tragically, as with all such ideological arguments, at this point there was no rational path that America, getting ever more deeply divided on this matter, could follow in order to get the country back together morally and spiritually. Ideological war was on, and on fully.

Memorial quilts laid out on the DC Mall in memory of “AIDS victims” – 1987

Once again, the Supreme Court gets in the game. Helping the Liberal cause greatly was another Supreme Court decision, the 1987 Edwards v. Aguillard case. Here the Court, in a 7-2 vote that June, set aside as “unconstitutional” a Louisiana directive that public education was to include the discussion of Christian “creationism” alongside the Secular idea of a purely material creation. The Court claimed that this directive promoted “religion,” instead of standing (as per the 1971 Lemon v. Kurtzman case) exclusively with only a Secular approach to education, the Court once again deciding which worldview (religion) American youth were to be taught. The Christian worldview, long America’s foundational worldview, was not to be passed on to future generations, by Supreme Court decree. Thus the First Amendment was not to be read as the freedom of religion, but as the freedom from religion. And the same amendment’s declaration that “Congress” (meaning federal authority) was also not to “establish” any form of religion had just been dismissed again by the Supreme Court, in favoring Secularism over Christianity. Not the people’s choice exactly.

1987 – the Rehnquist court

Only Justice Antonin Scalia (back right) and Chief Justice William Rehnquist (center) dissented from the Edwards v. Aguillard decision

Reagan in trouble: The Iran-Contra Affair

In November of 1986, halfway through Reagan’s second term as president, a newspaper story that first appeared in Lebanon made its way to the American press, revealing high-level political activity that potentially could have made Nixon’s Watergate scandal puny by comparison. It revealed that America had sold weapons to Iran in exchange for the release of American hostages held in Lebanon, the funds from that sale used then to support a CIA-backed military group of “Contras,” attempting to overthrow the Leftist Sandinista government of Nicaragua.

True, by political standards, these made great sense. But by U.S. law, all of this was highly illegal. It was long standing that no money was ever to be paid for the release of hostages, lest it encouraged the practice of kidnapping. And a Democrat-Party-controlled Congress had recently responded to the problem of spreading Communist insurgency in Central America by passing a law making it impossible for America to get involved in the matter, in any form or other.

The secrecy of the Contra operation thus was truly a shocker, one that the press loved deeply (the press always loves scandal!). And the Democrats were also very pleased in that they had the grounds by which to degrade, possibly even bring down, another popular Republican president,* through the party’s new weapon, impeachment by the House of Representatives, even though they did not most likely have the two-thirds majority in the Senate necessary to convict him and remove him from office. Thus a grand political party time was expected by both the Liberal press and Congress’s Democrat majority.

Reagan quickly turned the matter over to a three-man commission to look into exactly how all this transpired. But things did not turn out exactly as the Democrats had expected, when the commission announced (February 1987) that it could find little involving Reagan directly. And Reagan then apologized for not being on top of things, but also explained the importance of setting hostages free and of working to improve relations with Iran. Then also, public hearings (June-August) by both the House and the Senate really could not connect Reagan to events. Ultimately Congress issued a joint report in November also concluding that there was nothing in all this to charge Reagan with. That was wise of Congress, because even in the midst of the hearings, Reagan’s approval rating had dropped no lower than to just slightly under 50 percent, and then soon thereafter rose again quite quickly. Impeaching Reagan would not have been a wise thing to do.

New developments abroad

The reason that Reagan’s approval rating jumped back up so quickly was because of the way that it was becoming increasingly apparent that the Cold War was finally coming to a close, with clearly an American victory in the process. Thus there was much to celebrate.

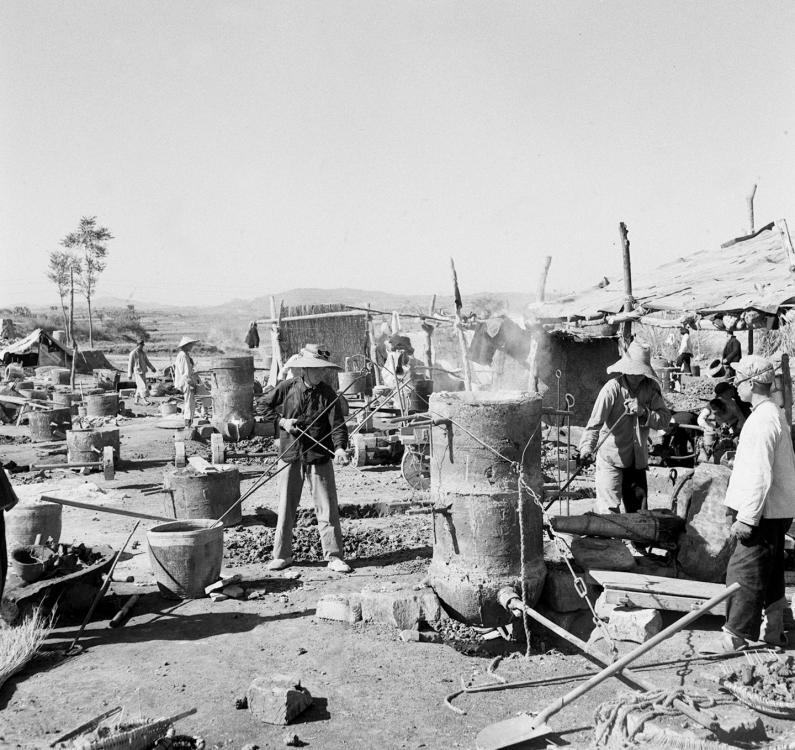

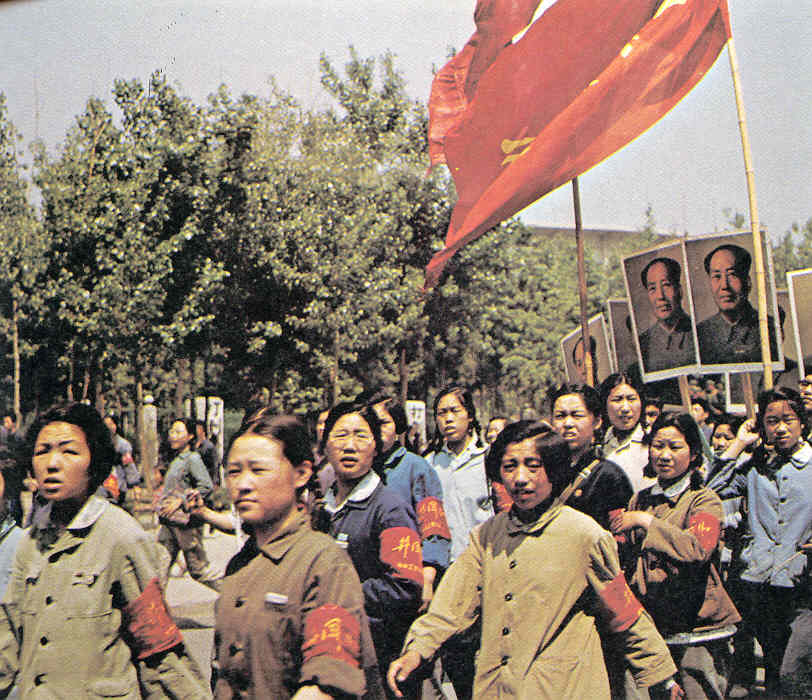

China moves away from Maoism. Since the Communist dictator Mao Zedong (formerly written as Mao Tse-tung) took control of China in 1949, America had largely avoided any dealings with China. America watched at a distance as Mao wrecked the Chinese economy in the late 1950s with his “Great Leap Forward,” taking the peasant farms away from their owners and then forcing farmers to work part-time in building village iron works, supposedly to show the world a distinctive Chinese way to become a great industrial power.

All he achieved in the process was to kill by starvation and exhaustion millions of Chinese, and his brief demotion from party leadership. But he made a political comeback in the mid-1960s when he caught Chinese youth up in a new Maoist ardor, the young instructed to oppose the conservatism of their Chinese elders, in order to put China on a path of true “Cultural Revolution.”

But once again, all this achieved was to throw China into chaos, and result also in countless deaths. But this time he survived a political reaction from the Chinese Communist Party, having previously removed his opponents, and because the party was so closely identified with the personality of Mao himself. But clearly Mao was losing his grip as China entered the 1970s.

Certainly Nixon’s visit to China in 1972 helped give Maoism a “new look,” a recognition of sorts that the Chinese-American portion of the Cold War was over, or at least coming to a truce of sorts. This certainly gave Mao a bit more respect both at home and abroad.

But Mao was aging rapidly, and clearly his close associate Zhou Enlai was having to take on much of China’s active leadership, though cautiously, because Mao’s very ambitious wife, former actress Jiang Qing, wanted to keep up China’s revolutionary fervor. And also Zhou, as well as Mao himself, were clearly developing health problems.

Ultimately, first Zhou, then Mao, died in 1976, and leadership was thus up for grabs. But party leaders were quick to put in place as leader the relatively mild Hua Guofeng, and arrest Jiang and the rest of her “Gang of Four.”

But actually, behind the scenes, power was increasingly found in the hands of Deng Xiaoping, who had survived Mao’s political purges, and was now moving to direct China in a more traditional way. China had not lost its instincts as an industrial society, especially in rapidly growing urban China. And Deng realized that Chinese strength was to be found in encouraging industrial entrepreneurship, rather than through revolutionary fervor. In short, he planned to open China to the huge international industrial realm of capitalism, as a fellow producer, not as its enemy.

But actually, behind the scenes, power was increasingly found in the hands of Deng Xiaoping, who had survived Mao’s political purges, and was now moving to direct China in a more traditional way. China had not lost its instincts as an industrial society, especially in rapidly growing urban China. And Deng realized that Chinese strength was to be found in encouraging industrial entrepreneurship, rather than through revolutionary fervor. In short, he planned to open China to the huge international industrial realm of capitalism, as a fellow producer, not as its enemy.

Consequently, by the mid-1980s, with Deng in full command of China, it was clear to the world that China was now an open society, quite able to participate most capably in the international production and commerce game. Under Deng’s direction, the Chinese economy was growing rapidly, at an average of 10 percent a year, an astonishing growth rate! And the world, including Reagan’s America, was more than willing to now work with China in that development, for it also helped their own economies to link their production with China’s growing production.

Clearly, there was no longer any “Cold War” going on between China and the West. In fact, such relations were now quite warm in character.

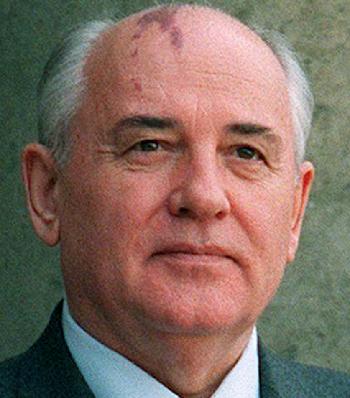

Russia attempts to go down a similar path. When Soviet Russian leader Brezhnev died in late 1982, his place was grabbed by Soviet hard-liner Yuri Andropov, former KGB head. It looked as if the Cold War might be starting up in Russia again. But only a little over a year later he too died, and was replaced by the aged party bureaucrat Konstantin Chernenko. But Chernenko himself only served a little over a year before he too died (1985). He was then replaced by the young party professional, Mikhail Gorbachev.

But Gorbachev felt strongly that it was time for Russia to rethink its entire social strategy. Certainly the grand success of China, quite apparent to all at this point, had something to do with his interest in moving Russia down a more strongly industrial path. And he hoped to do so by inviting the Russian labor force to take a more active role in supporting such development. Gorbachev believed strongly that too much bureaucratic management had been the cause of the stalling Russian economy.

But Gorbachev felt strongly that it was time for Russia to rethink its entire social strategy. Certainly the grand success of China, quite apparent to all at this point, had something to do with his interest in moving Russia down a more strongly industrial path. And he hoped to do so by inviting the Russian labor force to take a more active role in supporting such development. Gorbachev believed strongly that too much bureaucratic management had been the cause of the stalling Russian economy.

It would take only a year (1985-1986) of removing opponents and replacing them with supporters for Gorbachev to find himself ready to put his perestroika (reform) program into full operation. Although he had no interest in putting Russia in the capitalist camp, he did free up some of the restrictions against local private enterprise. Then hoping to enlist a more supportive Russian workforce, he introduced the policy of glasnost, allowing an “openness” in public matters, in political affairs, in the press, even in the streets and homes. Interestingly, this tended to divide quite strongly the “hardliners” who were quite alarmed by these reforms and the “liberals” who felt that they did not go far enough in freeing up Russian society.

A Russian practicing glasnost on a Russian street

Of course America, and in particular Reagan, was delighted to see Russia go down this path of reform. Indeed, in his several meetings with Gorbachev, Reagan wanted to make clear the extent of support that America felt for what Gorbachev was trying to achieve, even though it never seemed to go fast enough.

Reagan and Gorbachev at their first summit – Geneva – 1985

Indeed at one point (June 1987), as Reagan stood before a crowd gathered at the Berlin Wall, Reagan offered this challenge:

. . . if you truly want peace and liberalization, Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

BUSH Sr. TAKES COMMAND

George H. W. Bush

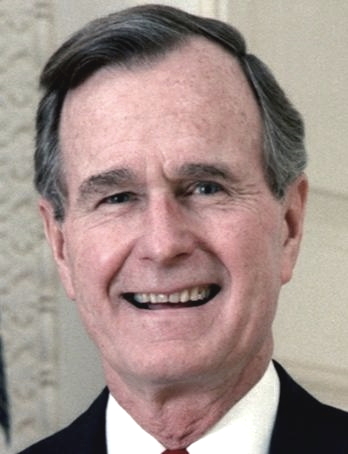

But it would be Reagan’s Vice President, George Bush, that would get to see that challenge finally come to success, when Bush himself took the helm as U.S. president in 1989. Bush was born and raised as something of a New England aristocrat (attending Phillips Academy), shot down in the Pacific as a navy pilot during World War Two, graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Yale in 1948, and then moved to Texas, there to prosper greatly in the rising oil industry. When his father was elected to the U.S. Senate, his political world opened greatly, though he would not himself attempt to get into that world directly until the mid-1960s, when after a failed attempt in 1964 he was elected as a Texas representative to Congress in 1966. A failed attempt to run as a senator in 1970 led instead to his being appointed by Nixon as America’s U.N. ambassador, during the height of the Vietnam crisis. Then Nixon promoted Bush as chairman of the Republican National Committee, putting him at the center of Republican Party politics.

But it would be Reagan’s Vice President, George Bush, that would get to see that challenge finally come to success, when Bush himself took the helm as U.S. president in 1989. Bush was born and raised as something of a New England aristocrat (attending Phillips Academy), shot down in the Pacific as a navy pilot during World War Two, graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Yale in 1948, and then moved to Texas, there to prosper greatly in the rising oil industry. When his father was elected to the U.S. Senate, his political world opened greatly, though he would not himself attempt to get into that world directly until the mid-1960s, when after a failed attempt in 1964 he was elected as a Texas representative to Congress in 1966. A failed attempt to run as a senator in 1970 led instead to his being appointed by Nixon as America’s U.N. ambassador, during the height of the Vietnam crisis. Then Nixon promoted Bush as chairman of the Republican National Committee, putting him at the center of Republican Party politics.

With Ford becoming president in 1974, Bush was then sent to China as something of an American ambassador (not yet fully recognized), where he developed further his Realist understanding of the dynamics of politics, national as well as international, namely, that it is vital to be strong but not domineering in the use of power. Then after a year in China, he was returned to the States to head up the CIA, though with Carter’s election in 1976 he was soon replaced in that role.

He thus returned to the business world in Houston, but kept his eye on Washington, deciding to make a run for the Republican presidential nomination in 1980. He backed out of the race when it became clear that Reagan was likely to be the winner, but accepted the offer to run as Reagan’s vice president (designed to strengthen the support of the more moderate wing of the Republican Party). And for the next eight years he would serve Reagan and America quietly and loyally in that role. And now, winning most handily in the 1988 elections,* it was his turn at national leadership.

The collapse of the Soviet world

What suddenly began to unroll in the Soviet East at this point had little to do with American politics or diplomacy directly, but instead was simply the unintended results of Gorbachev’s efforts to free up the heavy hand of Soviet authority. And the dynamic of this new glasnost was watched very closely not only in America and across the world, but also in Soviet-controlled East Europe.

The Soviet Empire crumbles (1989). Actually, Poland had begun its own effort to move in this “freeing” direction some nine years earlier when Polish dockworkers and their “Solidarity” organization shut down Polish imports and exports in a move to improve their economic status. Polish authorities were able to bring such independent action back under control − before a much-feared Russian intervention should occur. But the spirit still was alive in Polish hearts nonetheless.

And thus in mid-1989, Poland got the ball rolling when Solidarity won Poland’s national elections and formed the first non-Communist government in the Soviet bloc. And Gorbachev let the matter rest as such.

This was then the signal for other countries in the Soviet bloc to move in that same direction, Communist leaders resigning when public demonstrations made it quite clear of their lack of popular support, and even their support from Gorbachev’s Moscow. And quite dramatic was the general assault on the Berlin wall by masses of young Berliners, demanding that the wall should come down, their actions going unopposed by failing East German Communist authority.

And that December (1989), Romania arrested, quickly tried, convicted, and executed Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu (and his wife) – with no response from Moscow.

The Soviet Union itself crumbles (1989-1990). But the crumbling of Soviet authority did not end there. Various non-Russian republics within the Soviet Union began to announce their own withdrawal from the Soviet system. In late 1989, the three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania pulled out. Then in early 1990, Ukraine, Georgia, and others followed suit. Even in Moscow and other Russian cities, people were gathering in massive numbers to support Moscow mayor Boris Yeltsin’s desire to withdraw even Russia from the Soviet Union, to set it up as an independent republic – but in union with other newly freed republics as the Russian Federation.

Yeltsin addressing the multitudes in Moscow – 1991

Communist hardliners were furious about these developments and in August of 1991 attempted a military coup against Gorbachev. But they got trapped in the Russian Parliamentary Building when soldiers fired on them rather than on the crowds, the crowds being led by Yeltsin. But at this point Gorbachev found himself without support anywhere, and in December resigned as “President.” The Soviet Union no longer existed.

China and the Tiananmen Square tragedy (1989). None of this seemed to be lost on young Chinese, when in April of 1989 thousands gathered in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, demanding similar freedoms from Chinese Communist Party rule. At first Deng simply ignored the gathering. But as the weeks went by the number of students encamped there numbered perhaps as many as a million. And similar protests were now underway elsewhere in China.

Finally Deng made his move on the night of June 3-4, having a massive number of troops move in on the protesters, to completely clear the square. And the next morning they were gone, along with the lives of countless youths who resisted the attack. But as far as the protest went, it was all over.

The West, and Bush in particular, were quite critical of the Tiananmen putdown, Congress even voting to cut off all further military sales to China. But Bush soon backed down in his opposition, trying to keep things positive between China and America. Anyway, life went on in China as before, except that Deng himself stepped back from leadership, turning things over to Jiang Zemin, Jiang actually part of the reformist group.

But Jiang also chose to govern directly, unlike Deng, who had done so indirectly, in a way that shared power with others.* Thus once again, the Communist party and the Chinese state had come under the command of a single individual. This phase of Chinese liberalization was thus now at an end. More traditional Chinese political instincts were reviving in China.

The Gulf War or “Desert Storm”

Oil had been a huge motivator in the way the Ottoman Empire was carved up at the end of World War One. For instance, the country of Iraq was set up under British supervision in a way that combined the oil fields in the South of old Mesopotamia, where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers flow into the Persian Gulf, and where the Arab population there is highly Shi’ite in its Muslim loyalties, with the oil fields way to the north in the region inhabited by the non-Arab but quite Sunni Muslim Kurds. In between those two areas lay the Sunni Arab world.* Connecting these three regions as the single country of “Iraq” was done so in order to make access to the larger realm of Iraqi oil north and south so much easier for the British.

But also, given the deep animosity existing among these divergent ethnic and social groups, it was little wonder that Iraq would soon find that it needed a very tough hand, virtually a military dictator, to hold the whole thing together, once the British withdrew their political support. Eventually, in 1979, it was Saddam Hussein that would take up that role.

But also, given the deep animosity existing among these divergent ethnic and social groups, it was little wonder that Iraq would soon find that it needed a very tough hand, virtually a military dictator, to hold the whole thing together, once the British withdrew their political support. Eventually, in 1979, it was Saddam Hussein that would take up that role.

During the Reagan era, Saddam had actually been something of an American ally, at least to the extent that he found himself at war with neighboring Iran. Anything to humiliate Iranian authority after the Iranian Ayatollah Khomeini had declared “Death to America” seemingly served American interests quite well. And thus America was very generous in its financial and weapons support of Saddam’s mission to incorporate the oil-rich Arab-speaking, not Iranian or Persian speaking, portion of Southwestern Iran into Iraqi territory.

But things did not go well for Saddam. Part of the problem was that he did not get the fellow Arabs of that Iranian region to support his effort to “liberate” them from Persian domination, because Saddam and his governing Baathist (Resurrection) Party were Sunni and those Arabs inside Iran were strongly Shi’ite, like the rest of Iran. And those Shi’ite affiliations with the Iranians seemed to weigh more importantly in the hearts of those people than the Arab culture that they shared with the Iraqis. Consequently, after eight years (1980-1988), Saddam’s nearly bankrupt Iraq had to give up the effort.

Iraq’s poor showing in that war was a big part of the reason that Saddam then got the idea to take over the tiny, but oil-rich, neighbor to the south, Kuwait. To Saddam’s thinking, the area had always been a part of Iraq’s Mesopotamian world. And setting up Kuwait as a fully independent country apart from the Iraqi (and Saudi) world after World War One had been done largely to serve British oil interests.

But the British imperial role in the region had been replaced largely by the American hand, and Saddam believed that he would get no resistance from his American ally in simply taking over Kuwait, at least that is what he read from the American ambassador’s reaction when he proposed the idea to her in 1989.

But that was not Bush’s idea, or much of the rest of the world’s, that grew outraged when in August of 1990 Iraqi troops suddenly invaded and quickly took control of Kuwait. In November, the U.N., with American support, issued an ultimatum to Iraq, ordering Iraqi troops out of Kuwait.

Saddam now found himself in a bind. He hoped the world was simply bluffing, because to pull his troops out of Kuwait would constitute for him a major humiliation. Consequently, the matter dragged on, as Bush and others tried to get him to back down.

Finally, in early 1991, American troops, joined by other European and Arab troops, launched their own invasion of Kuwait from neighboring Saudi Arabia.

And in quick order, the Iraqi troops were driven back into Iraq, or simply surrendered.

So furious was Saddam that he ordered that all Kuwaiti oil pumping stations (700 of them) should be set ablaze as his troops pulled back, not realizing how quickly Red Adair and his Texas boys (and others) were able to put those fires out and cap the wells!

Also, with only four days’ effort and allied troops well within Iraq, all action ceased. Kuwait had been liberated. No further action was required.

Several years later (1994), when being interviewed at the American Enterprise Institute, Bush’s former Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney was asked why, with Saddam in clear defeat, American troops halted before capturing Baghdad, why Saddam was not simply finished off as a dictator. He explained in detail why it was a “quagmire” for America to fall in, if it should try to take over Iraq.

Wise words. Too bad they had no lasting quality, even for Cheney. But more on that later.

Some domestic issues

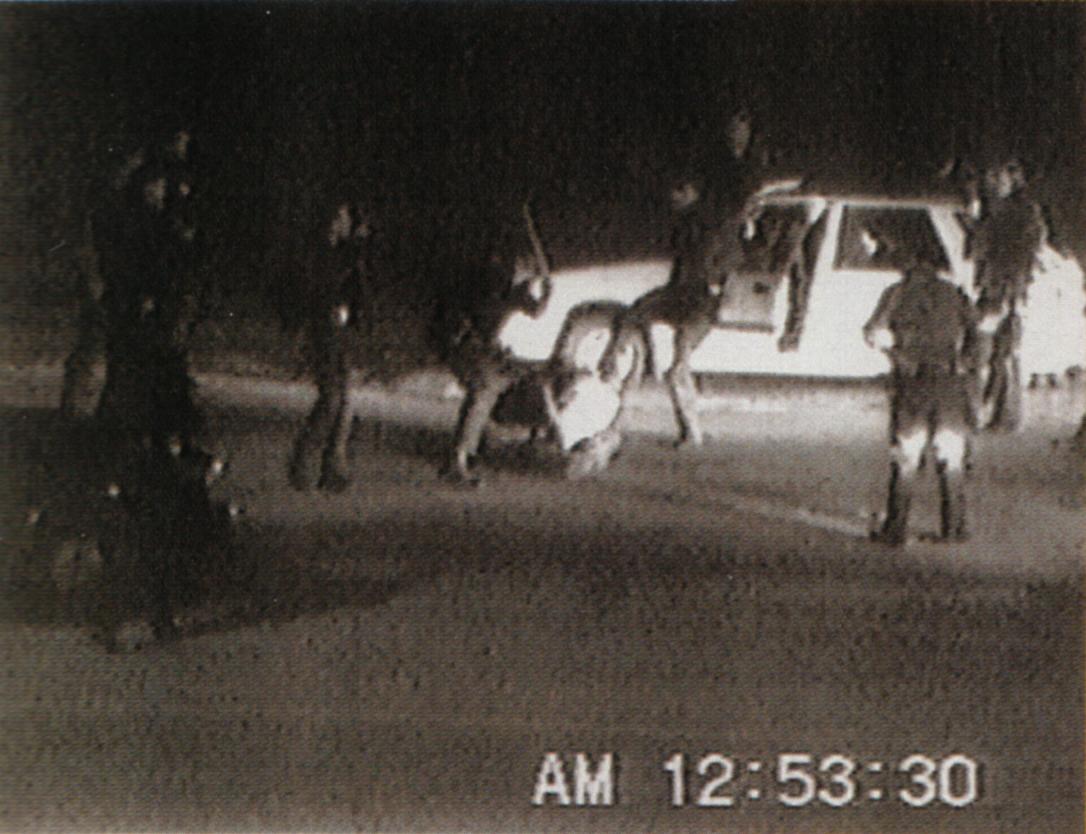

The Rodney King incident. An event in early 1991 that was to shake a fairly content America to the core was the most unexpected outbreak of racial violence … that broke out over the arrest – and beating − of a Black, Rodney King, by Los Angeles police officers. What set off the incident was the video filming by an observer of the event − and the broadcast of portions of the event by a local TV station − a presentation that quickly went national.

What the broadcast portion did not show was the events leading up to that moment: the police car and helicopter chase of an alcohol and marijuana high King and two companions across the L.A. Freeway and into a residential neighborhood … King at one point hitting 117 mph in the chase. He was finally cornered and stopped. He was ordered to the ground and handcuffed. But the full video (not part of the TV presentation) also shows King appearing to get up and charge one of the officers involved at that point … before being tasered, brought down, and then beaten by some of the other officers when he tried to get up again. But the beatings continued (the part shown publicly) … and King suffered a broken ankle and numerous cuts and bruises as a result.

The nation was so shocked – and long-serving (1973-1993) Black L.A. mayor Tom Bradly so outraged − that King was subsequently not tried for any of the offences of that night … but the officers were. But a jury, a year later, able to see the full extent of the encounter between King and the officers subsequently found the officers not guilty of any crime.

But this was not what the Black community wanted to see happen, and protests broke out locally, then spread quickly across L.A. (May 1992). After six days of rioting, state and federal troops were brought in to end the explosive violence. In those six days, 63 people had been killed, over 2,000 were injured, and 12,000 arrested. Also, thousands of buildings were looted and burned, with as many as 1,600 (or 45 percent of them) being owned by Korean shopkeepers, who were specifically targeted by the rioters. Estimates of the value of property-loss totaled over $1 billion.

Los Angeles on fire

Eventually, the officers were tried and convicted under new charges. And King sued the city of Los Angeles and was subsequently awarded $3.8 million for his pain and suffering, plus $1.7 million for his lawyers. Thus American justice was supposedly served somehow. King would continue to drink and take drugs, was arrested eleven more times, and finally drowned in his own swimming pool years later.

The fight over Supreme Court nominations. Most normally, presidential Supreme Court nominations received the scrutiny of the Senate largely only along professional qualification lines (the American Bar Association offering importantly its views on that matter) … with unanimous or near-unanimous approval typical of the results. But since Reagan’s nomination in 1987 of the conservative Robert Bork, political alignment now came into play on this matter (Bork was rejected for simply various political reasons). In 1990, Bush Sr.’s nomination of David Souter was fought strongly by feminists, the NAACP, and senators Kennedy and Kerry … Souter adjudged to be not sufficiently “progressive” as a future justice. Nonetheless he was finally approved by the Senate in a 90-9 vote.

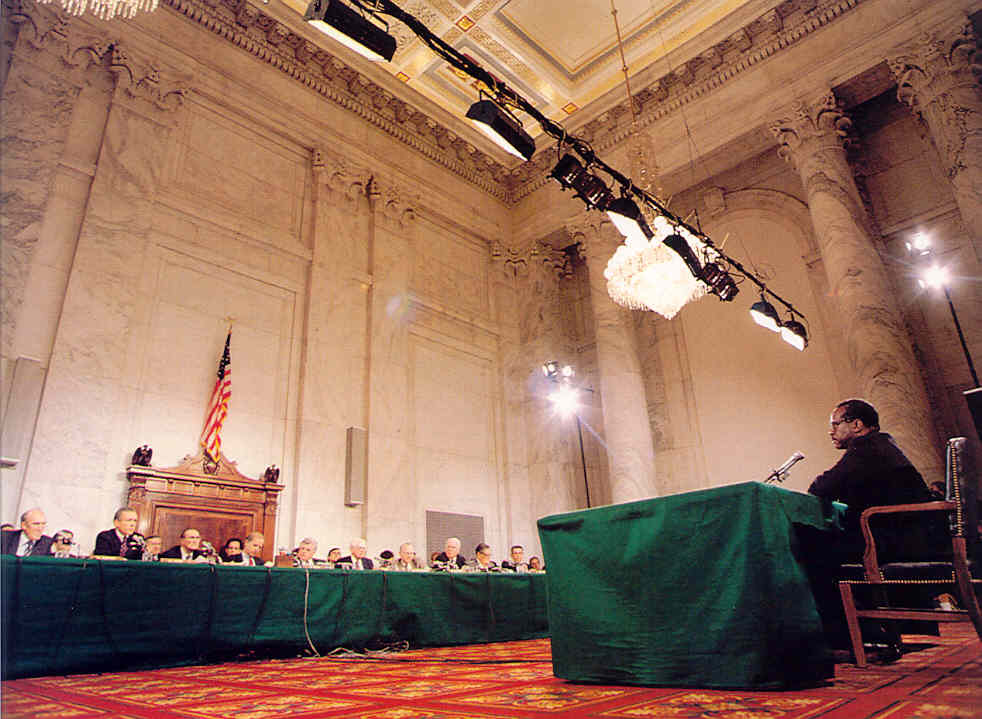

But the Liberal world would fight even more fiercely over Bush’s Supreme Court nomination the following year (1991) of Clarence Thomas … a Black Conservative! Being conservative seemed to be quite the betrayal of the Black civil rights movement … and the Liberals were determined to kill the nomination. It was well-known that Thomas considered government welfare to have crippled, not advanced, the wellbeing of the Black family and Black world … making Blacks even more dependent on government handouts – and less able to lift themselves out of their social predicaments.

But the Liberal world would fight even more fiercely over Bush’s Supreme Court nomination the following year (1991) of Clarence Thomas … a Black Conservative! Being conservative seemed to be quite the betrayal of the Black civil rights movement … and the Liberals were determined to kill the nomination. It was well-known that Thomas considered government welfare to have crippled, not advanced, the wellbeing of the Black family and Black world … making Blacks even more dependent on government handouts – and less able to lift themselves out of their social predicaments.

But such a view was considered to be dangerous heresy (even though independent studies clearly confirmed this to be the case) … and there was no way the Liberal world was going to let such an attitude finds its way into the all-important Supreme Court.

To kill the nomination, they eventually brought forward Anita Hill, who had worked for Thomas at the Department of Education … and then followed him when he was appointed as Chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). She claimed that his behavior to her was at times “inappropriate” … and called some fellow workers to testify on her behalf. But unfortunately for the Liberals, an even greater number of former Thomas employees pointed out that the behavior Hill described in no ways fit Thomas, it was Hill – in following Thomas from job to job – that was always the one pushing the relationship, and that Hill was a very ambitious individual well able to use political opportunism to get where and what she wanted.

To kill the nomination, they eventually brought forward Anita Hill, who had worked for Thomas at the Department of Education … and then followed him when he was appointed as Chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). She claimed that his behavior to her was at times “inappropriate” … and called some fellow workers to testify on her behalf. But unfortunately for the Liberals, an even greater number of former Thomas employees pointed out that the behavior Hill described in no ways fit Thomas, it was Hill – in following Thomas from job to job – that was always the one pushing the relationship, and that Hill was a very ambitious individual well able to use political opportunism to get where and what she wanted.

Thus the decision came down to the matter of which version of Thomas and Hill one was to believe … with the media and various political organizations taking exactly the positions on the matter that would have been expected of them. Finally, a deeply divided Senate approved Thomas’s appointment, 52-48, but only because 11 Democrats broke from the party ranks to approve Thomas. Interestingly, 2 Republicans opposed him.

But in any case, it was now clear that future Supreme Court appointments would be determined not on the professional qualifications of the nominees as judges, but on their most likely ideological loyalties in the midst of a political world dividing deeply. And of course this would only deepen further those very divisions.

CLINTON INTRODUCES THE BOOMER ERA

The 1992 election

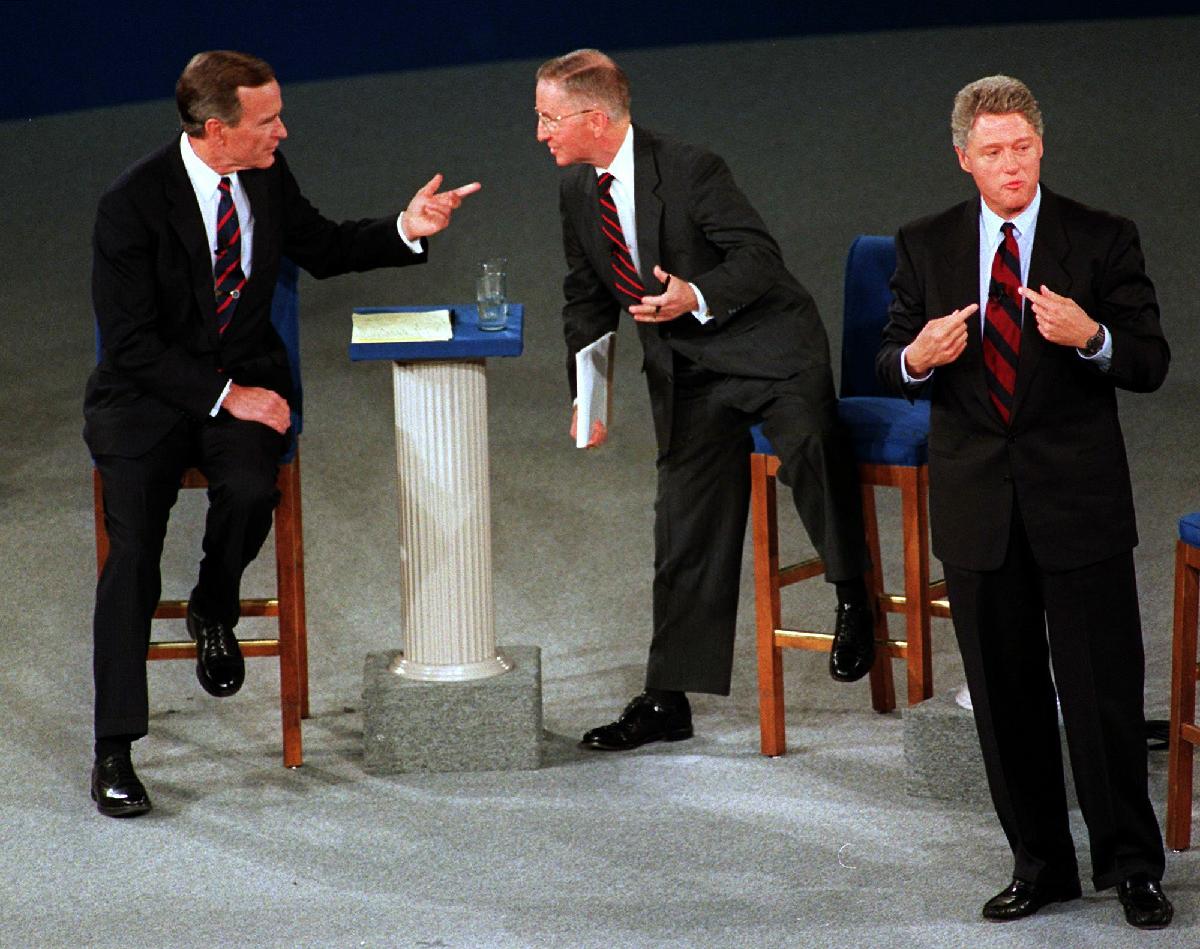

The three-way race. Although Bush certainly had proved himself as an internationally respected American president, the American economy had lost a lot of its luster, and Bush knew he had to raise the tax rate in order to keep the federal budget in balance, something that did not go over well with American voters. Actually, at the time of the election, the economy was already reviving, and about to head off in one of its longest and strongest growth periods ever. But the American voter did not yet know this.

Then too, a third-party candidate, the very successful Texas businessman Ross Perot, came on the scene with lots of ideas about how he was going to improve America. So wealthy was he that he was able to cover most of his presidential campaign expenses himself, allowing him all sorts of freedom to present himself however he wished. And he was proving to be quite popular, in June of 1992 polls showing him supported by 39 percent of the voters, ahead of Bush, with only 31 percent in support. And his Democratic rival, the young Bill Clinton (leading the Democratic Party nomination contest at the time) was registering at 25 percent.

But as of the election that November, Perot’s figure had dropped to 19 percent, Clinton’s finally totaled at 43 percent, and Bush’s at 37.5 percent. But the Clinton majority was spread so widely that Bush received only 168 Electoral College votes to Clinton’s 370 votes, a clear Clinton victory (Perot winning no particular state). Would Perot’s not having been part of the contest have enabled Bush to take the lead? In other words, did Perot steal votes largely from the Republican side of the picture? There really is no way to answer that question.

In any case, America was about to experience (actually only briefly at this point) what it would be like finally to come under Boomer Idealism.

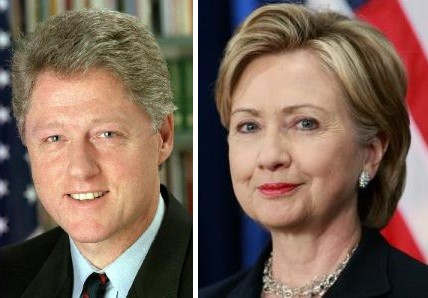

As Clinton liked to boast, “Two presidents for the price of one,” Clinton began his presidency with his wife Hillary, not merely filling the expected role of First Lady, but in fact as someone expected to preside jointly with him from the White House.

Indeed, what seemed to be his legislative priority, getting America under a national health insurance program, was assigned to Hillary to get the program put in place.

Hillary announcing her new health insurance program – 1993

Both Bill and Hillary came out of very strong educational backgrounds, Bill was a 1968 graduate of Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, even class president during his first two years, though he lost the race for the presidency his senior year because in this age of rebellion (1967-1968) he was judged to be too “pro-Establishment,” an amazing cultural trend at a university known for its strong political “Realism.” The next year (1968-1969) he lived abroad in Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, then returned to the States to attend Yale Law School, where he met and dated Hillary.

Hillary had graduated from Wellesley College in 1969 (at the time still a women-only college), when Hillary was the first student to deliver the commencement address, and received a seven-minute standing ovation, and also getting considerable national attention in the process.

Most interestingly, they both were strongly Christian in identity, Bill from an early age (only 9) taking himself to a Baptist church, in part to escape the brutality of an unhappy home life, and in part seriously to look higher to God for guidance. He would grow very close to the church’s pastor, W.O. Vaught, all the way up until Vaught’s death in 1989. And Bill would hold a lifetime admiration for the evangelist Billy Graham, when Graham came to town (Hot Springs, Arkansas) and refused to conduct his crusade on a segregated basis. Hillary grew up as a Methodist, and in Bill and Hillary’s earlier years together in Little Rock, Arkansas, taught Sunday School at the Methodist Church they attended.

And they were both deeply political in professional interest. Even as a youth, Bill worked very hard to be the very best in whatever field he was involved in (music, scholastics, social), to win whatever award there was to win, to be a leader. After completing law school, he returned to Arkansas to start up a law practice, and to teach law at the University of Arkansas. Hillary agreed to join him in both enterprises, even though she finally agreed to marriage only several years later.

Their wedding – 1975

Almost immediately (1974) Bill decided to run for the position as Democratic candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives, though he was defeated. Then he ran unopposed as the State’s attorney general, and two years after that (1978) he ran for the governorship, and won. He would be the nation’s youngest governor.

Unfortunately for him, his use of taxes to strengthen the state’s finances angered voters, who turned him out of office in 1980. But he, as the “Comeback Kid” (his own terms) learned the lesson (like Carter had to) of undertaking compromise in order to be effective to any degree, and was returned to the governorship in 1982. He would remain in that position for ten more years, until he became U.S. president.

Hillary, meanwhile, while active as a lawyer, also took up the task of overseeing the family’s finances, which ultimately led them somewhat blindly into the controversial Whitewater Development Corporation venture, which would later blow up as a huge political scandal when the Clintons were in the White House. Otherwise they prospered greatly.

And when in 1988 Bill delivered a (long) address to the Democratic National Convention, he found the political spotlight turned strongly on him when it was time, four years later, for the Democrats to pick a new candidate. And thus finally, the Clintons found themselves in the White House.

Compromise

Setbacks with their Boomer Idealism. Hillary would soon discover the power of the medical industry, which was hotly opposed to government management of the healthcare industry (the industry’s profits were immense!) and threw a full body block against her efforts to move even a Democrat-controlled Congress down her national healthcare path. Finally, she simply had to give up the matter.

The Clintons had also hoped, as most Boomers did at the time, that it was time to support open homosexuality in public life, in particular in the U.S. military. But, also at that time, Boomers were way ahead ideologically of the older members of American society, who were outraged at the idea. No way they would allow this to become public law. Finally a “compromise” was reached, requiring homosexuals to practice a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy of remaining discreet about their lifestyle. But this pleased neither side, although that would be where things would have to stand for a while. But by no means did this put the matter to rest.

Clinton also had a strong interest in seeing federal spending and federal income come into balance, by increasing taxes. In 1993, he succeeded in getting Congress to agree to support his effort to reduce the federal deficit, but only by the narrowest of margins, some Democrats even joining the minority Republicans in trying to oppose the measure. This victory, like the similar Arkansas effort, would end up costing him politically, though he himself would not lose office. But a lot of Congressional Democrats would.

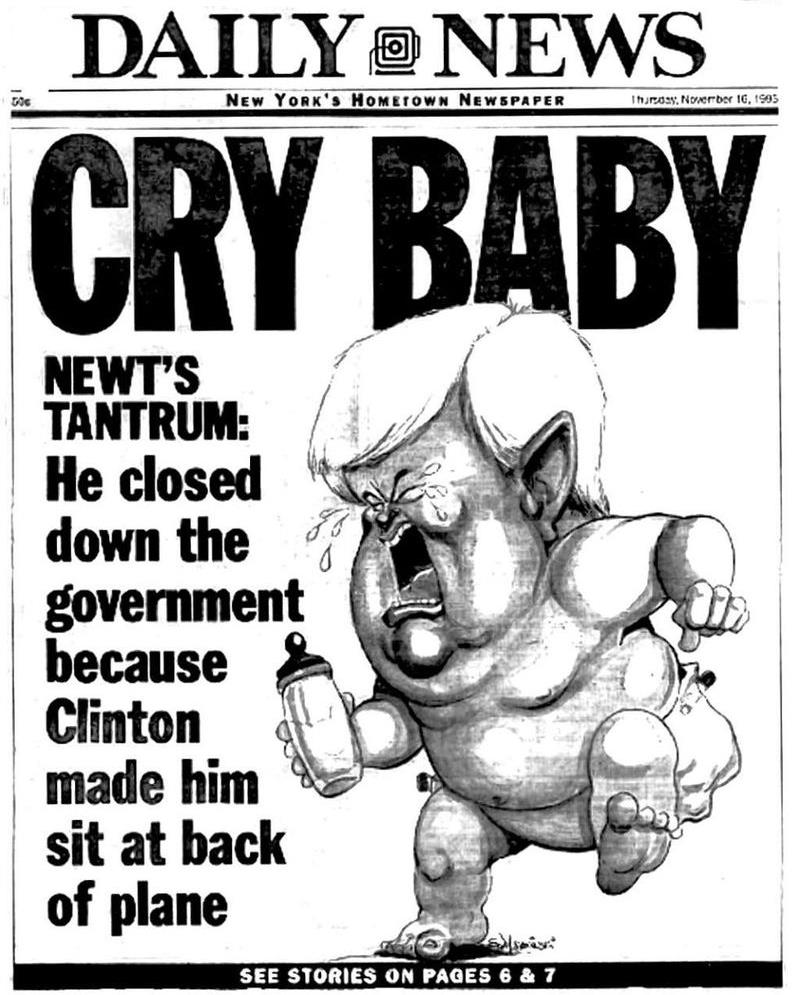

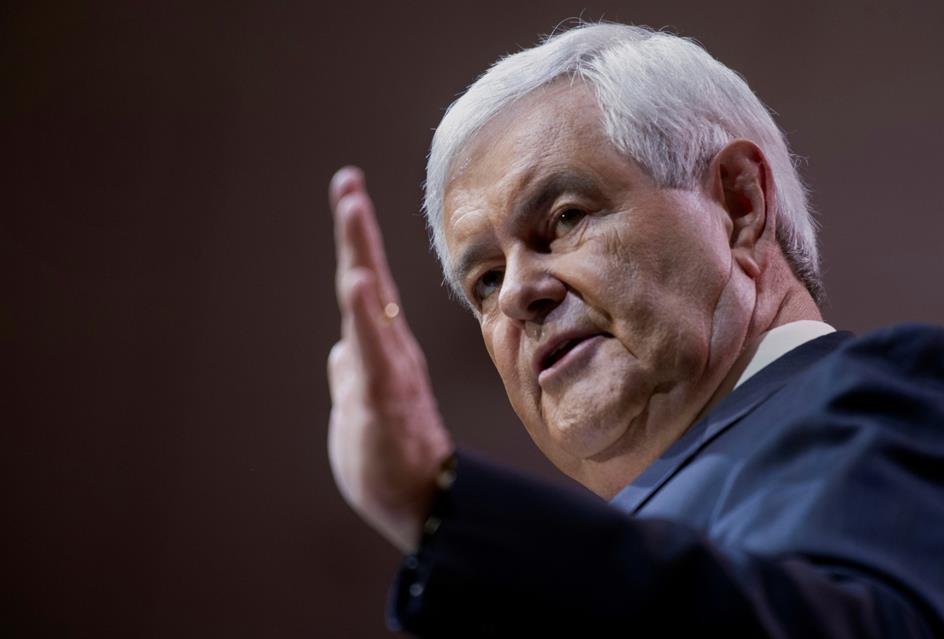

Gingrich and the 1994 Republican “revolution.” In the Congressional election of the next year, House Republican leader Newt Gingrich, in great part due to his vigorous campaigning, and the book he co-authored, Contract with America, was able to push forward a major Republican “revolution,” ending the Democrats’ 40-year control of the House, and 8-year control of the Senate.

Somehow this also brought Republican victories to numerous gubernatorial contests that year. What Gingrich did was to tap into the widespread concern across the country about how a rising Boomer generation (which included their president Clinton) was moving things in directions the majority of the country was not willing to go down.

The result was the passage of a number of pieces of legislation in the House (not always well-supported in the Senate and even vetoed by Clinton) which finally became law. Gingrich’s Republicans were dedicated to reducing the size of the federal government, and Clinton to vetoing those efforts, so that a stalemate resulted in 1995 and the shutdown of the government for a brief period, the Liberal press (as usual) depicting Gingrich as the villain in this standoff.

The result was the passage of a number of pieces of legislation in the House (not always well-supported in the Senate and even vetoed by Clinton) which finally became law. Gingrich’s Republicans were dedicated to reducing the size of the federal government, and Clinton to vetoing those efforts, so that a stalemate resulted in 1995 and the shutdown of the government for a brief period, the Liberal press (as usual) depicting Gingrich as the villain in this standoff.

Undoubtedly the most important legislation socially-culturally pushed by Gingrich was the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) refusing federal recognition of same-sex marriages, which even a majority of Democrats felt compelled to support. This included Clinton, who was not exactly happy about signing it into law, but smart enough to know not to veto it either. Besides, it had received the support of one of Congress’s largest majorities ever: 342-65 in the House and 85-14 in the Senate.

Clinton signing the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) – September 1996

Ultimately, Clinton found it wise to step away from his party’s Leftist instincts and move to the political center, stealing a good portion of the “revolution” from Gingrich by taking some of it into his own hands. For instance, he worked with Gingrich in supporting the deregulation of the banking industry, and in trying to bring the government deficit under control.

And he even finally (through compromise) supported Gingrich’s legislation, ultimately requiring 50% of federal welfare funding to the states to go to “workfare,” supporting the job training and placement of welfare recipients (mostly women) rather than just giving out money, in order to help them get on their own feet and thus end the state of total dependency that welfare payments typically produced. This did not make a number of Democrats happy. But it did make quite happy a huge number of welfare women, glad to be able to stand on their own (although, sadly, this did not work out as planned for some of them). And most interestingly, eventually Clinton went on to take as much personal credit as possible for this new “breakthrough” in welfare programming!*

Clinton and the world

America being at this point the world’s sole superpower, the world most naturally looked to Clinton to “referee” some of the nastier conflicts going on at the time, just as it had looked to Bush to bring the Kuwaiti crisis to an end. And most thankfully, in this realm Clinton would truly stand out, perhaps because of his Georgetown training, causing him to go at foreign challenges from a purely “Realist” rather than an “Idealist” position.

Somalia. In 1993, the U.N. looked to Clinton to help protect food donations to the Somali citizenry, starving from the horrible strife going on among various Somali political groups. But when he tried to land (via helicopter) U.S. troops in Somalia, and found the civilian population unwilling to endanger themselves by cooperating with their American protectors, he wisely pulled those troops out.

There was no point in getting involved in a situation where the locals were not going to be supportive, for whatever reason. Here too, like with Reagan in his pullout from Lebanon, Clinton found Americans deeply appreciative of his caution.

The Oslo Accords. That same year (1993) Clinton was able to follow up on Carter’s Arab-Israeli diplomacy, in getting Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat to come to an agreement on Palestine’s future. Sadly however, the agreement was brought to nothing when in 1995 an angry Jew killed Rabin over this matter, thus returning the Arab-Israeli status “back to normal.”

Haiti. In 1994 a military junta overthrew Haiti’s first popularly-elected president, Jean Bertrand Aristide, sending thousands of Haitians fleeing the country, many dying at sea trying to sail to America. Clinton sent Carter and General Colin Powell (Bush’s commander in Kuwait) to Haiti to warn the junta to return the country to democracy, or America would intervene. The junta believed that he was just posturing as a strong president, until Clinton actually got 20,000 American troops headed to Haiti. At this point the junta realized that Clinton had not been just bluffing, and stepped down, returning rule to Aristide. The world applauded!

Rwanda. That same year (1994), the U.N. looked to America to do something about the slaughter going on in Rwanda between the Hutu and the Tutsi tribes, with possibly as many as a million killed and many more forced to live as refugees. But Clinton refused, realizing that this problem was, like Somalia, way bigger than anything America would be able to handle. The killing of American soldiers trying to separate the two tribes would prove nothing, until the Hutu and Tutsi themselves cooled off. And they were thus going to have to do this themselves. The U.N. was disappointed, but the Americans were quite approving of Clinton’s refusal to get caught in a situation that offered nothing but pain for America.

Bosnia. But the situation in the former Yugoslavia proved to be quite a different matter. Since the death in 1980 of the one person holding this multi-ethnic society together, Josip Tito, the country had slipped step by step into a vicious rivalry among these various ethnic groups as they tried to establish the borders of their newly independent countries. The worst situation by the 1990s was the province of Bosnia, the population divided among Sunni Muslim Slavs (the largest group), Serbian Orthodox Christians, and Croatian Catholic Christians. The worst violence was between the Serbs and the Muslims, the Bosnian Serbs supported strongly by the new neighboring nation of Serbia, Serbia looking to expand its isolated country by extending its borders across Bosnia to the Adriatic Sea. Thus the Serbs of Bosnia had full backing of the Serbs of Serbia to drive the Muslims out of their country, mass slaughter involved in the program.

Civilians caught in the cross-fire between ethnic militants in Bosnia’s capital city Sarajevo

Here too, the U.N. looked to America to do something. But so did Europe, especially America’s close NATO allies, for this crisis had all the dangerous possibility of spilling over into the rest of Europe. Thus, in 1995, Clinton decided to act, through American airstrikes on Serbian troops, and with ground assistance coming from Muslim nations and from the Croatian military.

U.S. airstrike on a Serbian ammunition depot in Bosnia

Finally, toward the end of that year Serbia yielded (the Dayton Accords) with a 60,000-troop NATO monitoring force (20,000 of them American) put in place to enforce the accords by which Serbia agreed to recognize Bosnian independence. Things then quickly settled down in Bosnia.

The signing in Ohio of the Dayton Accords by the presidents of Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia – November 1995

Kosovo. But a similar situation heated up in 1999 in the former Yugoslavian province of Kosovo, vastly Muslim in religion and Albanian in language, but with significant Serbian minorities scattered here and there across that province, especially in the area bordering Serbia. Once again, Serbian president Milosevich sent troops into Kosovo to join local Serbs in what was turning into a civil war as bloody as the Bosnian mess. This time Clinton took the lead in responding to the situation, even bombing the Serbian capital Belgrade. This forced the Serbs to back off, and Kosovo ultimately to come under the protection of 50,000 NATO-staffed U.N. troops (7,000 American). Then Milosevich was arrested as a war criminal, and deported to The Hague (Netherlands), where he died in prison awaiting his trial. And Clinton received the great appreciation of the Kosovars, when they erected an 11-foot statue of him, atop an even higher pedestal, in their capital city, Priština!

Russia. With post-Soviet Russia now under Yeltsin, Russian-American relations became quite warm, just as the personal relations between Yeltsin and Clinton reflected that same warmth.

Yeltsin and Clinton having a good laugh together during Yeltsin’s visit to the U.S. in 1995

But beneath these appearances, Russia was in deep trouble. The Russians truly had no idea of how to do democracy. A number of younger Russians had the entrepreneurial spirit, and were thus able to make themselves quite rich. But the general population was raised with a dependency on higher authority, and did not do well economically under their perestroika/freedom. Economic depression thus hit hard, as did also a lowering life expectancy among the Russians, a formula for deep social-political problems to soon head their way. But for the time being this all stayed out of the limelight.

Iraq. Bush had allowed Saddam to stay in power in Iraq. But America kept a close eye on him because of a concern that he would attempt some kind of political comeback through military means. Americans were particularly concerned about the possibility of his resuming nuclear weapons development, ever since his nuclear reactor had been destroyed in an Israeli air attack back in 1981. Saddam was required to allow U.N. inspectors to check regularly on his energy programs, which by the 1990s America and Britain were growing concerned that Saddam was obstructing in order to conduct secret nuclear development. This then led Clinton to the decision in 1998 to join the British in conducting four days of aerial attacks (Operation Desert Fox) on various Iraqi sites, to degrade his ability to develop WMDs (Weapons of Mass Destruction), and even bring him down from power if possible. But this effort proved not to get the international support Clinton was used to, not only other Arab nations, but also Russia, China, and France proving opposed to the venture, even calling on the U.N. to end the boycott of Iraqi oil sales.

Broader Muslim problems. Why did Clinton do something that was quite likely to bring only reproach from the rest of the world? It seemed so out of character. Cynics stated that he did this only to distract American attention from the growing scandal about his behavior with a pretty White House intern. But in part it certainly developed from a growing concern Clinton and others had about the mounting hostility of the Muslim world (led in part by America-hating Iran), shockingly registered when in 1993 Muslim fanatics tried to take down the New York Twin Towers, succeeding instead in destroying only 6 floors of the parking garage, but coming close to succeeding in their venture.

And only a couple of months prior to the 1998 Operation Desert Fox venture in Iraq, Muslims had blown up huge sections of the American embassies located in Nairobi (Kenya) and Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), killing hundreds of mostly local employees and wounding thousands.

The bombing of the American embassy in Nairobi, Kenya

In any case, was Saddam involved in any of this? He had plenty of reasons, because of Kuwait, to want to see America brought down. But then so did other Arab groups, al Qaeda being one group under great suspicion. But at the time, all this posed itself simply as a huge mystery.

The Clinton era ends in scandal

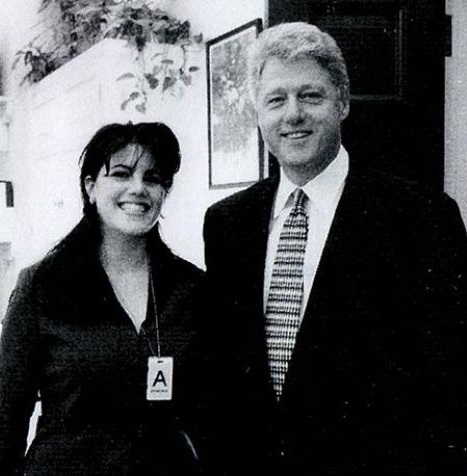

At the beginning of 1998 the press began to cover a growing scandal about sexual behavior between Clinton and a White House intern, Monica Lewinsky, certainly not the first time that such behavior occurred in Washington, where status, money and sex were quite often the underlying dynamic driving D.C. politics.

However, traditionally such matters were considered none of the press’s business. Look at how Ted Kennedy’s action at the Chappaquiddick bridge seemed to have little impact on his political career. But the media, not to mention politicians looking for a cause to advance their careers by taking down opponents, found that such a scandal was too profitable a matter to be passed over. “Monicagate,” as it was called in the way it paralleled Nixon’s “Watergate,” became quite the spectacle as 1998 and 1999 rolled along.

The Republicans try the impeachment maneuver. And the Republicans foolishly took up the tool of impeachment that the Democrats had previously found so useful in advancing their party’s career … well, at least in the case of Nixon, for impeachment did not go so well for the Democrats in the case of Reagan. And so now the Republicans would attempt the trick, except that it also would not go all that well for them.

Despite their huge majority in the House, the House voted impeachment only very narrowly, to then pass the matter on to the Senate for conviction, except here, most unsurprisingly, the Senate failed to gain the two-thirds conviction vote, in fact registering only a 50-50 tie vote.

Moving on. And somehow all this failed to bring the American public along in the matter. It actually led to the creation of an online organization, moveon.com, which minimized the matter as much as possible, and then went on to be a very effective voice for the Democrats in future controversies and elections. And the Clintons themselves (with important counsel from Christian evangelist Billy Graham) decided to “move on” as well, saving the marriage, and the political status of both Bill and Hillary.

Gingrich goes down. But ironically, the Republican voice of Gingrich was what came down in all this, Gingrich already in trouble himself when an affair in the mid-1990s with a woman (who would become his third wife)* while married to his second wife was brought to public attention.

In January of 1997, Democrats, sensing a grand opportunity, had brought some 84 ethics charges against Gingrich, ultimately convincing the House Republicans to join them (395-28) in at least one charge, reprimanding him for the use of a tax-exempt college course, Renewing American Civilization, for “political purposes.”* And with Gingrich now leading the attack against Clinton, this all smacked of highly public hypocrisy.

When in November of 1998 the Republicans lost a number of House seats in the Congressional elections, it finally led Gingrich to resign, not only his leadership position in the party but even his seat in the House representing his home district in Georgia. Gingrich was simply quitting.

Go on to the next section:

America Wanders off Course