CHAPTER TEN

AMERICA DIVIDES

MAJOR SOCIAL-POLITICAL ISSUES AT HOME

“A wall of separation between church and state”

In the early 1960s the Supreme Court took the amazing steps to outlaw both prayer and Bible reading in America’s public schools, doing so in accordance with the principle of the separation of church and state.

It all started innocently enough with a Supreme Court decision in 1947 in the Everson v. Board of Education case, supposedly at that time actually authorizing public support of school busing for children attending private schools, because it did not violate a constitutional “wall of separation between church and state.” That decision supposedly therefore supported the role of religion in American education.

But what was this principle concerning “a wall of separation between church and state”? That was a Jeffersonian concept, not a constitutional principle. Supposedly this was drawn from the First Amendment which reads:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Certainly something like Jefferson’s “wall of separation” can be interpreted as being implied in that First Amendment. But such a wall was intended to keep the state out of religion, stated very clearly in the second part of that statement about the act of “prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Keeping the state out of American religion was as important (even first on the list!) as it was to do the same in the realm of speech, press, public assembly and political petition. It was not supposed to be blocking any of those rights from being practiced by the people.

But having used this Jeffersonian term in its 1947 decision, in 1962, in the Engle v. Vitale case, the Supreme Court came to the 7-1 decision that a simple prayer, authorized by the New York Regents, violated the “constitutional wall of separation” between church and state and thus was forbidden.

The Warren Court – 1962

The prayer was fairly broad in definition:

Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our country. Amen

Several Jewish plaintiffs and two Secularists got the ACLU to back them in trying to get the prayer outlawed in 1959, but had failed in the lower courts. But now they got Warren’s Supreme Court to decide in their favor. This would be the beginning of the Supreme Court’s new role in building a wall of separation “preventing the free exercises thereof” in this matter of church and state − the exact opposite of what the First Amendment intended. In fact, it went against everything that had guided America forward, even to greatness, since its founding three centuries earlier: God’s guidance and protection. Because of this Supreme Court decision, American children were now to be directed away from just such dependence on God – freed to go at life the Secular-Humanist way.

At this point the Christian community found itself deeply divided over the Court’s action. On the one hand were much of the clergy of the mainline Protestant churches and their large religious alliance, the National Council of Churches, which saw no anti-religious bias in the Court’s decision. Their viewpoint was that this decision did not actually forbid prayer in public schooling, only official prayers. On the other hand were the Catholic and Evangelical clergy, who knew that preventing Christian public education was indeed being instituted by the Supreme Court. Time would soon prove which of the two had things right.

Then two years later in another case, Abington Township School District v. Schempp (1963), one brought by Unitarian parents and again the ACLU, the Supreme Court decided also that the reading of the Bible in public schools was forbidden by the First Amendment. At this point it was very clear that the Supreme Court was indeed preventing the free exercise of religion in the nation’s public schools.

But for most Americans, their understanding was that their rights came from God, rights protected by the Constitution, not from some state agency such as the Supreme Court, extended through the Constitution. There was a huge difference between those two ideas!

Sadly, this would be merely the beginning of the Supreme Court’s decision to begin to reshape the nation’s personal freedoms and its constitutional laws along political lines supporting the religious instincts of the Secular Humanists, lines which were, as clearly demonstrated in their 1933 Humanist Manifesto, quite opposed to America’s long-standing Christian religious traditions and social foundations.

This was hardly the Supreme Court’s right to re-legislate America’s moral-religious-spiritual foundations. But from this point on that is exactly the role the Supreme Court took for itself. In fact, it would even act in such a way that it, not Congress, would become America’s supreme legislative body.

But it all happened so gradually, in such small steps, that it caught much of the country unaware of what was happening.

Actually, in Congress in 1963, in reaction to this court decision, Representative Frank Becker was quick to propose a constitutional amendment to make clear that voluntary prayer and Bible reading could not be prevented by any state agency. The “Becker Amendment” had wide support in Congress, but could not get past the actions of the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, Emanuel Celler, a Liberal-Democrat Jew who had no intention of letting the legislation get out of his committee. Becker then came only one vote short of forcing the bill’s release before the full House. From that point on, the matter just dragged on, until Celler was able to make it just die as an issue. The Secular Humanists had again won the battle.

Actually, in Congress in 1963, in reaction to this court decision, Representative Frank Becker was quick to propose a constitutional amendment to make clear that voluntary prayer and Bible reading could not be prevented by any state agency. The “Becker Amendment” had wide support in Congress, but could not get past the actions of the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, Emanuel Celler, a Liberal-Democrat Jew who had no intention of letting the legislation get out of his committee. Becker then came only one vote short of forcing the bill’s release before the full House. From that point on, the matter just dragged on, until Celler was able to make it just die as an issue. The Secular Humanists had again won the battle.

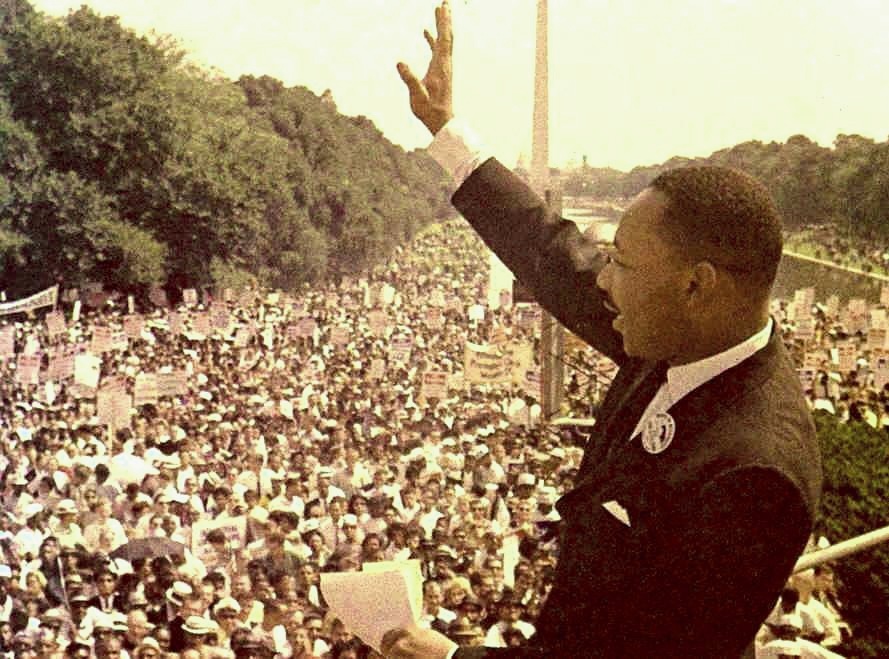

Martin Luther King, and the March on Washington (August 1963)

Another event that was to have a huge impact on America – actually highly integrative rather than divisive – was when Alabama pastor Dr. King organized a massive march on Washington in the summer of 1963, his desire to make it clear to America (and the world) that the discriminatory treatment of American Blacks (particularly virulent in the South, and most notably Alabama) had to stop. He gave America a dream to pursue, namely that the day was coming when Blacks and Whites would work together as a single people.

And indeed, he well planted that dream among Americans, which then set off a huge round of civil rights legislation making such racial discrimination fully illegal. However, through his efforts, America would have full racial equality not only through Congressional legislation, but also through the change in human hearts.

Kennedy’s assassination (November 22, 1963)

But then America was soon shocked to hear the news that Kennedy had been shot and killed in an open-car procession through the streets of Dallas, Texas.

The presumed assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, who had apparently fired a long range shot from a distant building, was himself soon apprehended. But he too was shot during a police prisoner exchange by an individual with his own deep emotional problems, Jack Ruby. As a consequence, an effort to discover the whats and whys of the Kennedy assassination would never be clear, despite a 10-month inquiry into the matter by a committee headed by Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren. Rumors would thus abound, the truth never really known.

THE WORLD OF LYNDON JOHNSON

The transition. However, other than the shock of seeing their president Kennedy killed and then his vice president Johnson legally take his place, the general expectation was that America would simply carry on as before. Other than some annoying international developments (in Cuba and Vietnam, for example), there seemingly were no great international issues confronting America. And aside from the Black civil rights issue, which Americans felt that they were finally dealing with through changes in the hearts of White America, there was little of urgent political character to be dealt with domestically either.

Johnson being sworn in as U.S. president on the flight back from Dallas

Anyway, at the time, “government” was still considered to be simply that of the American people themselves, what they did and decided to do. Washington was merely representative of that domestic governmental force, not the actual government itself. True, the Great Depression and World War Two had led to a very activist Washington administration. But that was considered merely a matter of the huge urgency of the times, and only a temporary matter. And indeed, after World War Two, things went quietly back to normal in Washington

But under their new president, Johnson supposedly just a rather “good old boy” Texas Democrat politician of whom little out of the ordinary was expected, things would change in Washington, and do so dramatically.

Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ). Johnson grew up in relative poverty at a farm in rural Texas. He went to college with the idea of becoming a teacher, taking a year off to teach Hispanic children, which touched his heart deeply. But in 1930, a job teaching in Houston opened the door for him to Texas politics, when in 1931 he worked in a congressional campaign and ended up following Congressman Kleberg to Washington as an aide. There his instinct for fellowship widened his social circle considerably, including staff working for Roosevelt. Ultimately, he became close friends of fellow Texans Vice President Garner and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn.

Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ). Johnson grew up in relative poverty at a farm in rural Texas. He went to college with the idea of becoming a teacher, taking a year off to teach Hispanic children, which touched his heart deeply. But in 1930, a job teaching in Houston opened the door for him to Texas politics, when in 1931 he worked in a congressional campaign and ended up following Congressman Kleberg to Washington as an aide. There his instinct for fellowship widened his social circle considerably, including staff working for Roosevelt. Ultimately, he became close friends of fellow Texans Vice President Garner and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn.

In 1934 he married Claudia (“Lady Bird”) Taylor of Texas, touched with an aristocratic Southern background based in Alabama, the two forming a blend of Southern cultures that would shape deeply Johnson’s understanding of his role as U.S. president.

He would become a major New Deal Program administrator, training unemployed Texas youth, adding considerably to his understanding that those in power should take particular care for those dependent on their leadership. And finally running successfully for Congress himself in 1937, he would now have the opportunity to put his political philosophy to work. However, in joining the Naval Reserve in 1940 he would soon be called to service as a congressional investigator into navy contracts, similar to Truman’s work in the Senate.

In 1948 he won Texas’s Democratic Party nomination for the Senate (under questionable circumstances), and thus rather automatically the Senate seat itself in Texas’s still highly “Dixiecrat” (Southern Democrat) society. This would be the beginning of a career in the U.S. Senate that would have him become Democratic Party minority leader in 1953, and then majority leader with the Democratic Party victory in the Senate in 1954. And with this, the office of U.S. presidency came into view for Johnson.

But, as we have seen, he lost out to Kennedy in the 1960 Democratic Party presidential nomination but was willing to accept the passive position as Kennedy’s Vice President – where he ultimately had little political importance during those brief Kennedy years. But now, as of November 1963, he was finally U.S. President.

And what America was about to receive was a Johnson, not very glamorous, but bent on proving himself as a champion of the poor and oppressed, both at home and abroad. And that champion would be the U.S. government in Washington, not the U.S. government in the hearts of the American citizenry. Unlike Kennedy, or even Martin Luther King, Jr., Johnson did not have the confidence that the American people were up to the challenges facing the nation. For instance, he had seen how American Southerners dug in deeply in opposition to the call to end the horrible discrimination against American Blacks. He thus did not see the political potential in just a popular appeal, in a call to the Americans to do the right thing. In rather aristocratic style, Johnson believed that Washington was going to have to do that for them.

Johnson’s “Great Society”

In May of 1964, in a speech delivered at the University of Michigan, Johnson announced his new Great Society Program, one that would build on American wealth and success to further the progress against poverty and social injustice still lingering in America, most notably in urban America. He also stressed the need to protect America’s environment against overcrowding and pollution, and the need to improve American education.

At the time, he proposed calling working groups to work together on these matters, giving some appearance of building his program on the thoughts of the Americans themselves.

Democrats become the party of “Let Washington take the lead” (“Progressivism”). But ultimately, he would simply rely on a Democratic-Party-controlled Congress to pass the legislation that would allow him to expand the bureaucratic programming in Washington that he personally felt was needed to put his program into operation.

And indeed, overnight, the Washington bureaucracy expanded greatly in size and impact on America. A massive bureaucracy composed of technical professionals would now govern in the area of poverty, injustice, environmental matters, and American education. Thus America came under the governance of what the French call “technocracy”: government by the technical experts, or what I like to call “democracy from above.” This, of course, is no democracy at all, just simply Socialism. Socialism is where those in authority promise to take care of the people under their “care,” at the expense of others outside that realm. It certainly has its appeals, if the costs involved are not carefully explained as well.

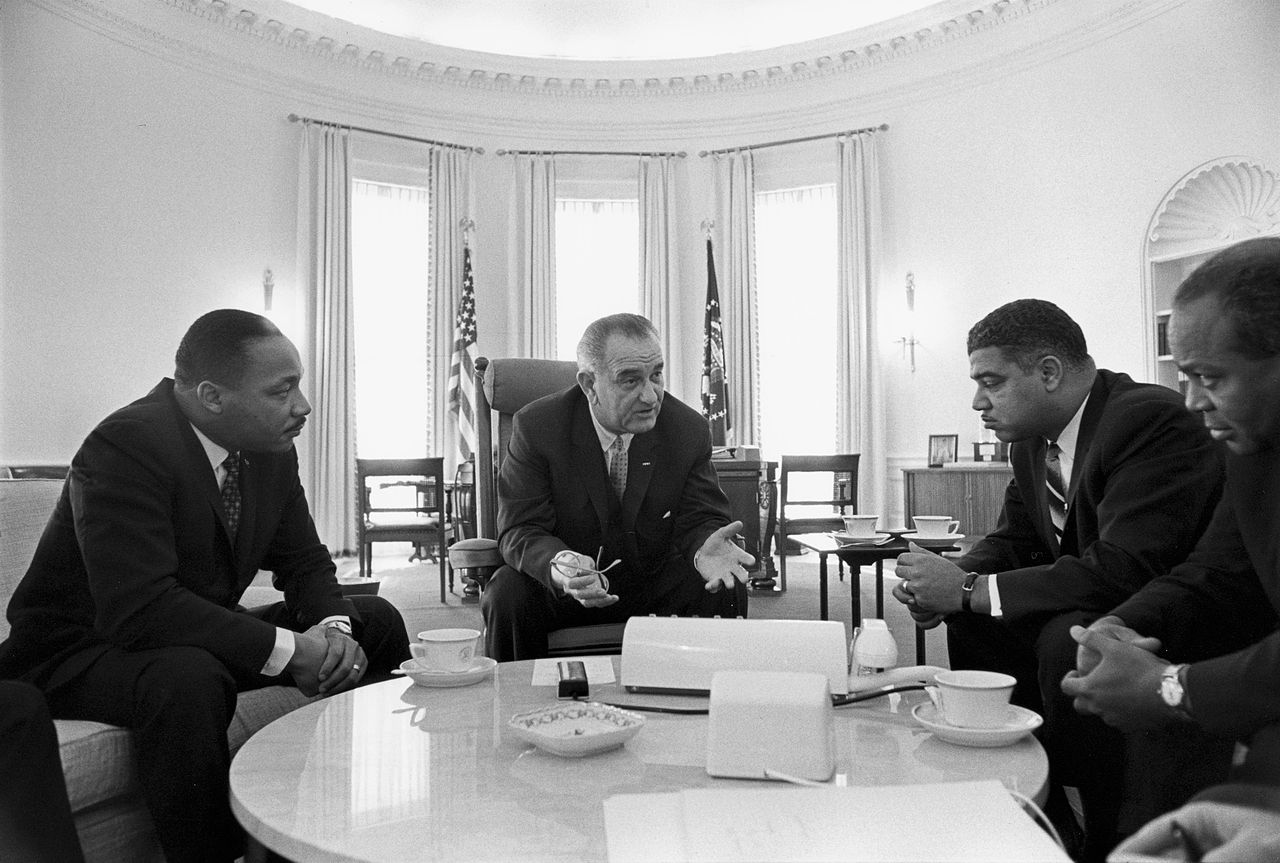

Johnson discussing with King and others the way Black living standard can be improved through Congressional legislation

And thus the Democratic Party, already strongly influenced by Roosevelt’s New Deal, became the party of “democracy from above,” running up a huge government debt in the process.

Massive federal spending. For Americans, this was when Johnson would have Congress cover the rising federal budget deficit by adding to the overall budget figures the rather large surplus in the Social Security Trust Fund. But the Fund was supposed to stand quite independent of the federal government and its spending. But Johnson insisted on now making it part of federal operations. But even then, including the very positive Trust Fund figures, this would not balance the budget. And worse, the Fund would then be required to “lend” its financial assets to the federal government to help cover the shortfall of the massively increasing federal budget, leaving the Fund only with federal IOUs instead of real wealth. The Fund was thus eventually to become nothing more than another Ponzi scheme, which paid out retired investors not on the basis of supposed interest earnings, but in reality simply on the basis of money coming in from workers still contributing to the Fund. Otherwise, there would soon be nothing of real value, except federal debt, left in the Fund.

Adding to this Washington aggrandizement was Lady Bird’s strong desire to see the city of Washington change from being something resembling that of a mere state capital, to the kind of impressive quality one should expect of the governing city of a great society or empire. Washington needed to be “beautified,” and beautified greatly. Thus Washington set itself not only to grow in size but also to do so in grandeur.

LBJ and Lady Bird Johnson

Vietnam

Johnson felt he had the answer to the mounting problem of Vietnam: a limited “police action” designed to end the Communist insurgency in the southern half of the country.

A Buddhist monk burning himself in Saigon, South Vietnam’s capital, in protest against communism? (actually against Western intervention in Vietnamese affairs)

But to justify such military intervention, he was going to need Congressional backing, and that would have to come from some kind of “cause,” which Johnson carefully set up so it would appear that North Vietnam had acted aggressively (twice even) against innocent American involvement in the region. It was rather phony, but worked in getting congressional authorization for his “police action.”

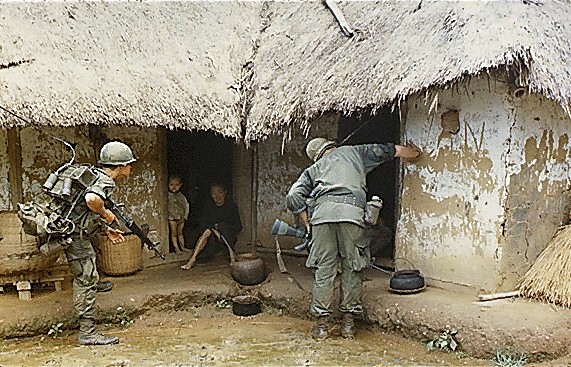

Vietnam is a long but very thin line of territory that runs along the west coast of the South China Sea. Johnson’s plan was simply to unload American troops at various points along that shore line (the South ‘Vietnam portion anyway) and then move them quickly inland in order to bring various sections of the country quickly under American control.

But he really hadn’t thought things through, or just had no idea of what it was that was most likely to happen in the actual operation itself. It looked so clear on a map. But in fact, once ashore, American troops could not distinguish between the Vietnamese they were there to save and the Vietnamese that would be opposing the American invasion. They all dressed and acted alike. Consequently, in passing through a village and freeing it from Communist control, they would soon find themselves being attacked from behind by some of those same villagers.

Searching for the enemy – 1966

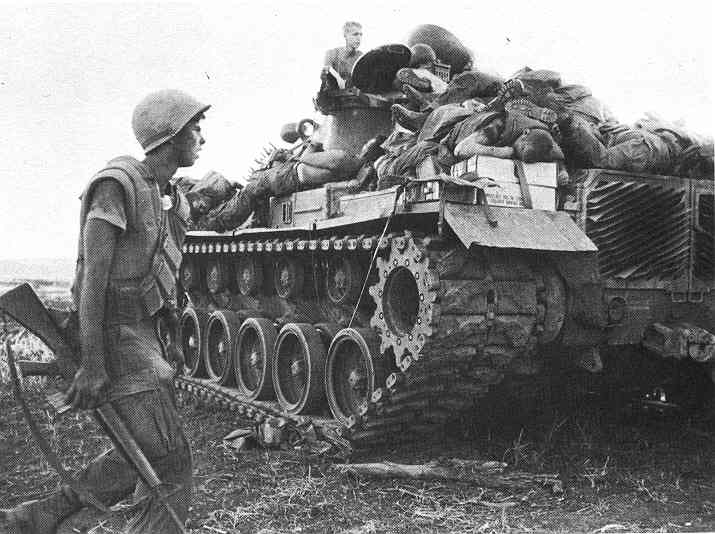

Johnson would send more and more troops (American boys now drafted in huge numbers into military service) to deal with the problem, a problem that remained unchanged no matter how many troops (over a half a million serving there towards the end of his presidency) he sent to Vietnam. Ultimately the best these troops could do, aside from shooting up suspicious villages and using Agent Orange gas to strip the countryside of its woodlands where the Vietnamese fighters (the Viet Cong) could hide out, was to simply stay within the bounds of their own military camps and hold on to those as their “gains” in this war. There were no front lines, no colored areas on military maps that showed any gain against the enemy, because the enemy was everywhere, mixed in with a population that basically just wanted to be left alone so that it could go about the business of just living quietly and peacefully.

Dead marines being transported back to base camp – 1967

The 1968 blowup at home

By 1968, on two fronts, one concerning Johnson’s social “progress” at home and the other concerning his Vietnam War abroad, Johnson found himself facing a very upset American citizenry. The Vietnam issue was a pretty straightforward matter: Americans were very tired of this war, and of the lives of young American soldiers it was costing. Anti-war protests were building in number and size, especially among the draft age youth, but girls protesting as well as draft-eligible boys.

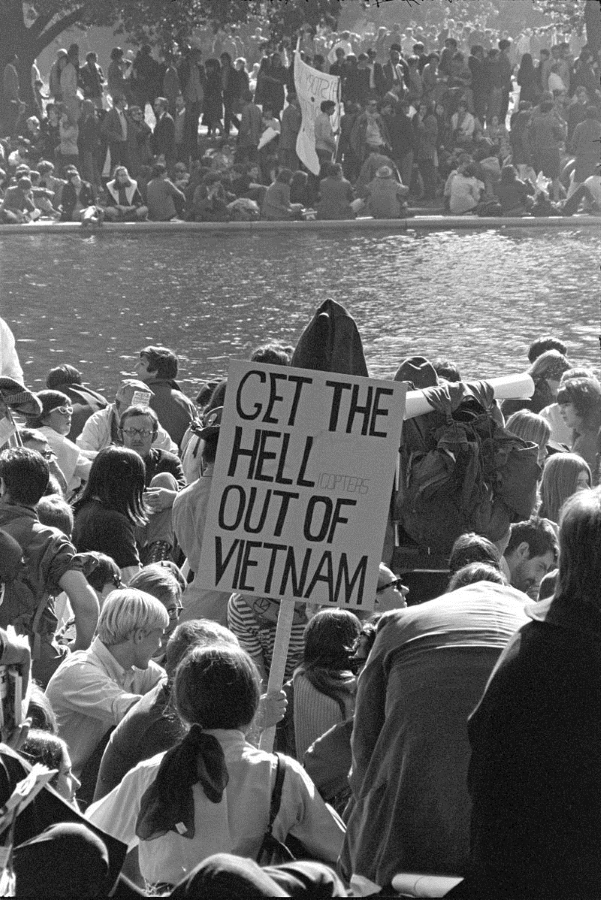

Anti-war protest in Washington – 1967

And in January of 1968, Viet Cong fighters were able to attack massively American troops, even in South Vietnam’s capital city of Saigon … and even kill the marines stationed at the American embassy there. Americans were shocked. But Johnson clearly had no exit plan for Vietnam.

As far as the matter of social progress at home, in particular the matter of race relations, anti-White militancy among Blacks rather than Black appreciation for changes underway in American society seemed to be the visible result.

Black Panther leaders Bobby Seale and Huey Newton

The rapid growth of the militant Black Panther movement, and the urban violence that grew quickly in Black neighborhoods (something rather typical of morally-unrestrained “revolutionary” behavior), was not what Johnson had expected.

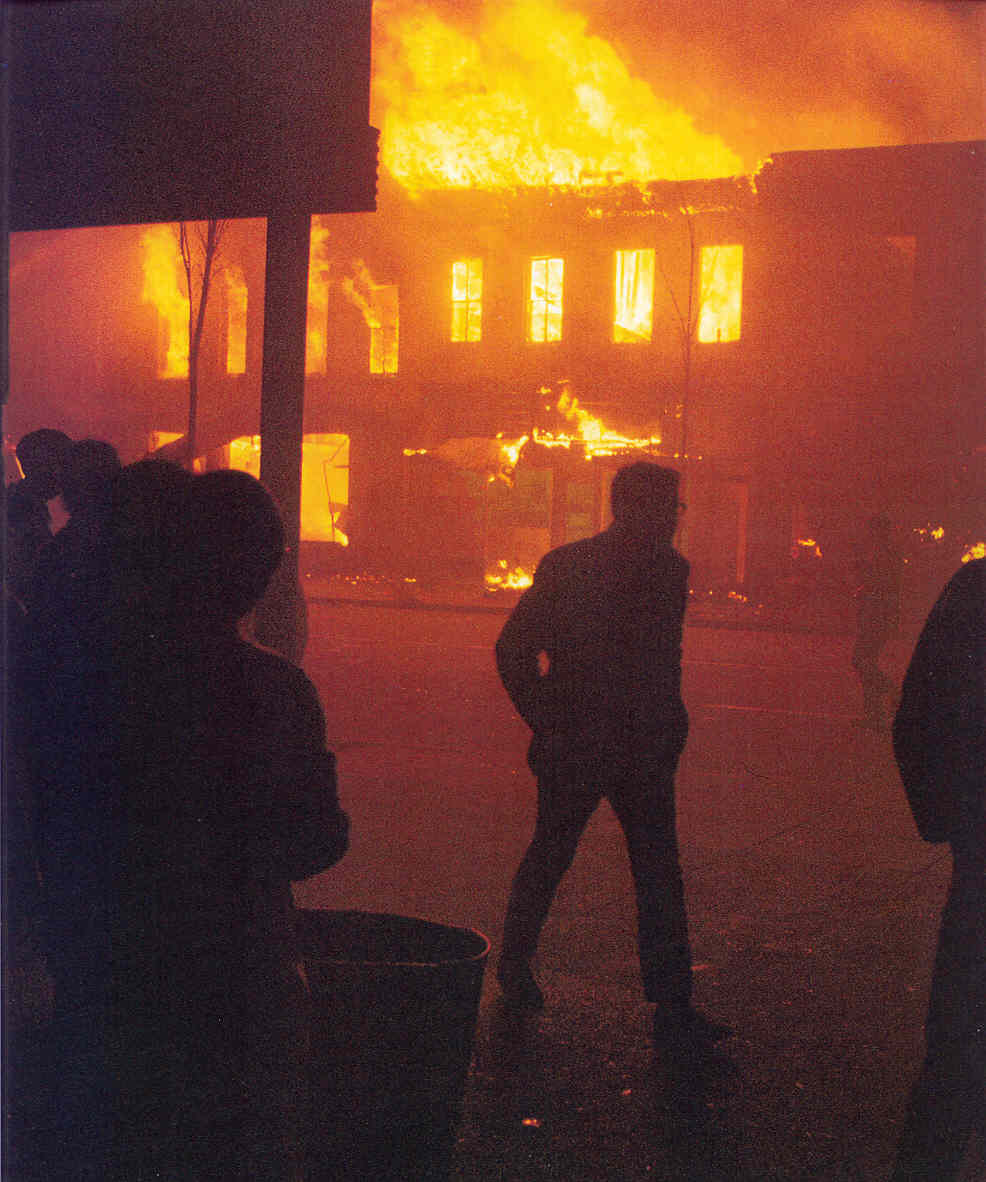

Detroit burning – 1967

Here too, Johnson had no idea of what to do next, except in March of 1968, at the end of a speech, he added the announcement that he would not be running for re-election in the coming November’s national elections. He would be leaving the White House in January of the coming year. All of this turmoil would be someone else’s to deal with. That was his only plan.

Johnson announcing his retirement

But the following months would only see things get worse − much worse. In April, Dr. King, who had switched his program from Black civil rights to civil rights of all the poor − White as well as Black − was shot and killed by a White, apparently therefore authorizing Blacks to begin to burn American cities in protest (not exactly what King himself would have wanted to see happen). This included huge sections of Washington, D.C.

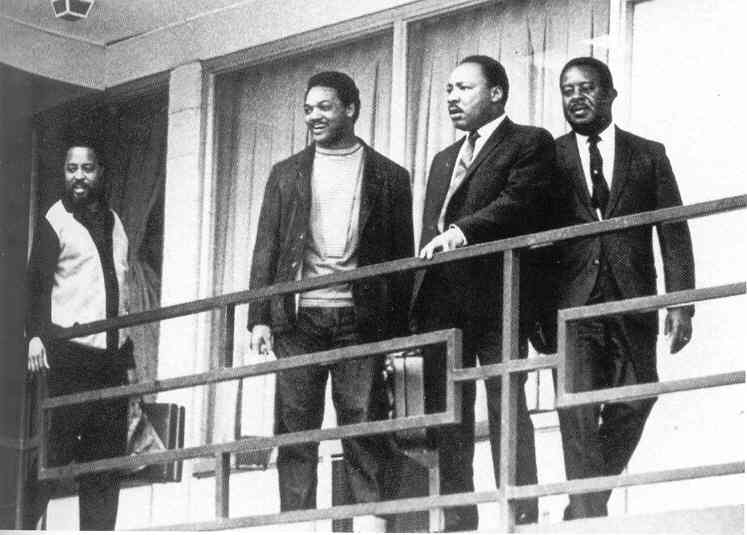

Dr. King on the same balcony where he would be shot the next day

Washington burning

As a follow-up, White students at Columbia University in New York City shut down the university in protest against the “racism” of the university executives with their decision to build on property owned by the university, but used by locals (Blacks mostly) to plant gardens. Things then got violent when students anticipating graduating that June themselves came up against these protesters.

Then in early June, Bobby Kennedy – who was clearly in line to be the Democratic Party nominee … and most likely the next American president – was also shot and killed.

Also, a campaign of Dr. King to bring massive numbers of America’s poor to Washington in June in support of anti-poverty programming was held despite Dr. King’s death, now to honor King. But it rained almost every day, turning the Washington mall into a soggy, muddy tent city, which finally disbanded in July, without any significant congressional action taken on the matter of poverty. It was all very depressing.

Then at the Democratic Party nominating convention in Chicago in August, chaos reigned, especially with the gathering of masses of Boomer youth protesting the convention (protesting what exactly?), and the Chicago police answering in kind.

Boomer “Yippies” in Chicago protesting against everything imaginable

The world goes on without American involvement

So preoccupied was America with the Vietnam War and the American social program at home that, during the Johnson era, it seemed to have simply stepped off the world stage, to let the world find its own way forward without any other American superpower involvement.

De Gaulle’s France. Taking advantage of this American distraction was French president de Gaulle, ever-hostile to the Anglo-Saxon world. He had long resented the English-speaking world – especially as it took the lead in matters during World War Two (France was not in an honorable position at the time).

In 1959 he pulled his Mediterranean fleet out from under NATO command, and ordered all American nuclear weapons removed from France − presuming that this would then put continental Europe under only France’s nuclear protection. Then in 1963 he struck a blow against the British when he vetoed their application to finally join the EEC. That same year he withdrew his more strategic Atlantic Fleet from NATO command, hoping other European NATO members would do so. None did. The following year he undertook visits abroad (Moscow and Latin America) and transferred French political recognition from Taiwan to Mao’s China … in order to present France as something of a “neutral” in the Cold War … and to encourage others to move in the same direction − particularly America’s friends in Latin America (they did not take the bait however).

Then in 1965, he sent ships to America to collect American gold reserves in exchange of the dollar reserves held by France − hoping to create a global gold rush on America, which would ruin the American economy. Here too, none followed his lead. But it still hurt the federal treasury greatly.

Then in 1966, he ordered all NATO troops out of France − to which Johnson’s Secretary of State sarcastically responded by asking if that was also to include the 50,000 American soldiers buried in France during World War Two! But the whole of NATO command, and not just the troops, then decided also to join the move north into Belgium.

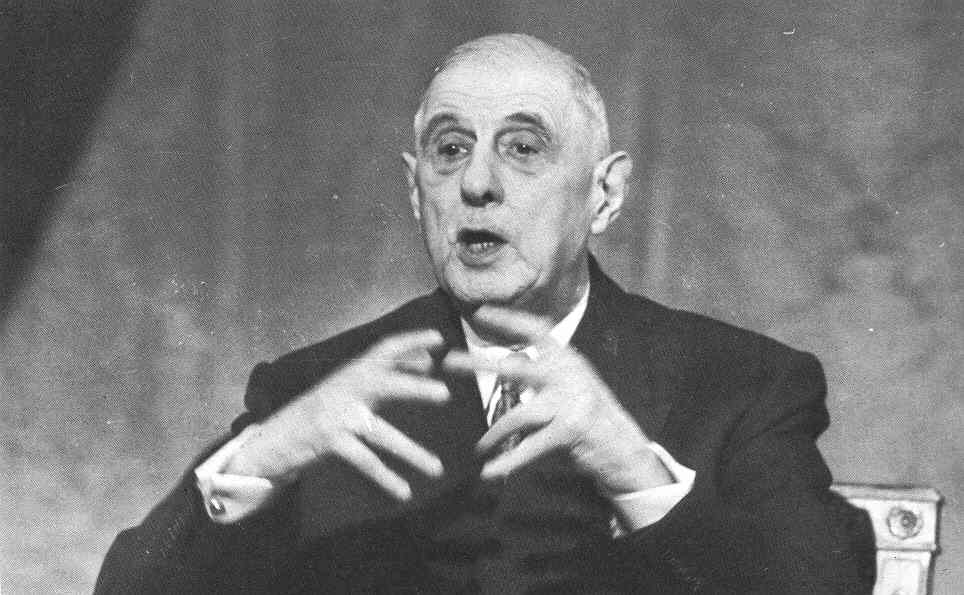

De Gaulle at a press conference – 1968

Finally, the French themselves had enough of De Gaulle, when in 1968 he demanded that the French amend their 5th Republic constitution according to some measures he wanted to see put in place, threatening to resign if they did not approve his proposal in a national plebiscite. Much to his shock they did not fall under the threat and refused to go along with him in this matter. He then in 1969 resigned, expecting France to fall apart, and the French to come pleading for him to return to power. But none of this proved to be the case.

And with de Gaulle out of power, Britain finally was able to join the EEC, and America was able to get on with its role as leader of the West, with France and America once again on quite friendly terms. And de Gaulle would die the following year (1970).

The Arab-Israeli Six-Day War of 1967. America had stayed rather neutral on the matter of millions of European Jews moving into the Arab world of Palestine, not sure which of the two groups America should be supporting. Both sides had strong moral cases for themselves, the Jews needing to get away from a hostile Europe, and the Arabs certainly being entitled to live freely in their own lands. Perhaps also some Americans in strategic political positions were aware of the huge percentage of that Arab population that was in fact Christian, and had no desire to see fellow Christians chased from their homes by invading Jews. But in general, this was not something that the American media (certainly more Jewish than Palestinian in makeup!) felt that America needed to be aware of.

The Arabs, not only in Palestine but in the much larger surrounding Arab world, remained incensed about the Israeli treatment of the Palestinian Arabs, a matter that Arab politicians played to their own advantage. Notable in that regard was Nasser of Egypt, who once again was playing big on this matter. It seemed even at one point that he was willing to attack Israel to drive home his point. But Israel decided not to wait to see what he was up to, and instead themselves did the attacking. Without warning, in June of 1967, Israeli airpower destroyed Egypt’s airpower, still on the ground. This allowed Israel then to easily destroy a defenseless Egyptian army and move Israeli troops into Egypt all the way up to the Suez Canal.

Israeli troops celebrating their quick victory – 1967

Most foolishly, Arab allies, Jordan to the East and Syria to the north, decided to come to the aid of their Egyptian friends, and themselves were then smashed by Israeli countermoves. Very quickly (thus the term “Six Day War”), the war was over.

It was at this point that America came all-out on the Israeli side, at least on the part of the media − with Johnson himself still being quite cautious on the matter. The media portrayed the Palestinian groups still trying to defend Palestinian rights, principally the Palestinian Liberation Organization or PLO, as true villains, villains that America must oppose at all costs. Again, American officialdom was not yet there in that position. But complements of the way the media shaped the narrative, from that point on, it became quite instinctive for Americans themselves to see this matter entirely from the Jewish perspective.

The “Prague Spring” of 1968. Then there was the strategic matter of the Czechs attempting to break free from the Soviet Russian grip, with their “Prague Spring” in 1968. Normally America would have played some kind of role in this development, for it was on just such anti-Communist activity that America had long focused so much of its diplomatic effort. But that focus had been so completely directed to the single event of Vietnam that Johnson (who at this point had just announced his coming retirement from the presidency) had absolutely no support to offer the Czech freedom fighters.

Actually it was the Czech Communist leader himself, Alexander Dubček, who started this freedom momentum, by trying to liberalize the struggling Czech economy with open-market reforms, terming it all “Socialism with a human face.” At first, a shocked Moscow, now under the party leadership of Leonid Brezhnev, did not seem to react, except to try to get Dubček to back down on his reforms.

Dubček Brezhnev

But when it became apparent that Dubček had no such intention, and that American opposition was apparently not going to be any kind of a problem, Brezhnev announced his “Brezhnev Doctrine,” promising all-out defense of “Socialism,” and called on his Warsaw Pact “allies” (or subjects) to join Russia in putting an end to the foolishness going on in Czechoslovakia. Thus on the night of 20-21 August, he sent hundreds of thousands of troops and 1200 tanks (Russian, Bulgarian, Polish, and Hungarian) to take control of Czechoslovakia.

A Czech challenging a Soviet tank

Dubček saw that he had no choice but to advise his people of the pointlessness of trying to fight against the invaders, although of course there was just such action that took place here and there. But for the Czechs, it was all over very quickly.

Some noise about the matter was made at the U.N., with America joining with others to “look into the matter.” But little else resulted from this tragedy. And the world quickly moved on to other matters.

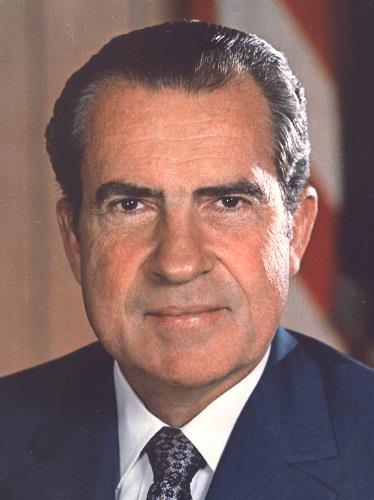

THE NIXON-FORD YEARS

The November 1968 elections turned out to be quite interesting, in that the Republican Party candidate (once again) Richard Nixon won only 43.4% of the popular vote, only slightly ahead of the Democratic Party candidate (and Johnson’s Vice President) Hubert Humphrey with 42.7% of the vote, the remaining 13.5% of the vote having gone to the Alabama Governor George Wallace, running as an Independent, taking a large number of Southern Democrat votes with him. But in the end, it is the vote of the Electoral College that counts, and Nixon won big there, 301 votes to Humphrey’s 191 votes, and Wallace’s 46 votes.

But at the same time, the Democrats held their position of control of both Houses of Congress. Thus a Republican president and a Democrat Congress were going to have to find some way to work together. But that was just not going to happen. In fact quite the opposite would characterize the coming Nixon years. Indeed, some very bad developments would hit America because of this deep political division within the country.

But at the same time, the Democrats held their position of control of both Houses of Congress. Thus a Republican president and a Democrat Congress were going to have to find some way to work together. But that was just not going to happen. In fact quite the opposite would characterize the coming Nixon years. Indeed, some very bad developments would hit America because of this deep political division within the country.

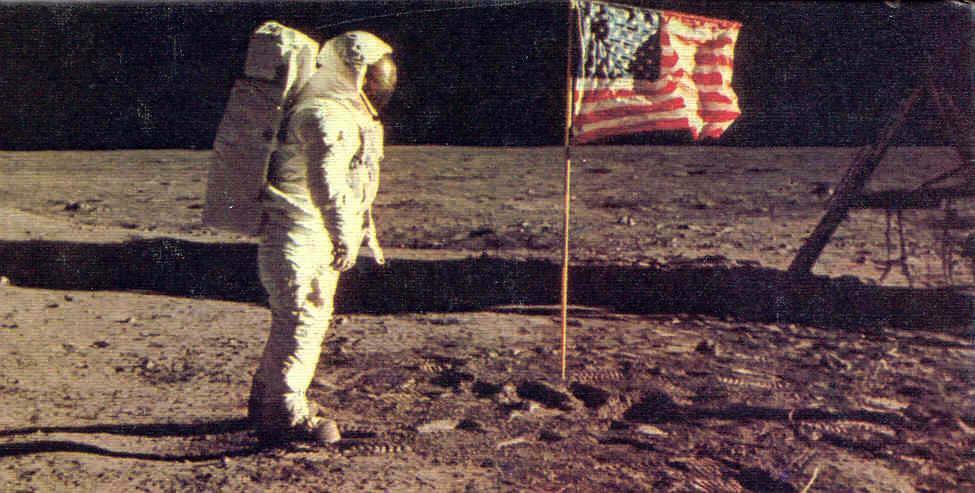

The American moon landing. But the Nixon presidency started off nicely enough, with the American moon landing of its astronauts that July of 1969. This was a result of presidential action begun well before Nixon’s arrival. But he and America were broadly gracious to all who had contributed to this grand success. It clearly put America ahead in the space race. Most wisely, Russia would not attempt a “second place” status with a moon landing effort of its own.

Buzz Aldrin planting an American flag on the moon

The American withdrawal from Vietnam. And America was very happy at the way Nixon managed to get American troops out of South Vietnam, without Vietnam collapsing into chaos, Nixon making it very clear to both South and North Vietnam how America intended to use airpower to protect the “democratic” legacy those years of American effort in Vietnam had produced.

There were anti-war protests that resulted from his demonstration of just such airpower, a particularly ugly demonstration at Kent State University in May of 1970, when nine students were wounded and four killed by nervous Ohio National Guard troops.

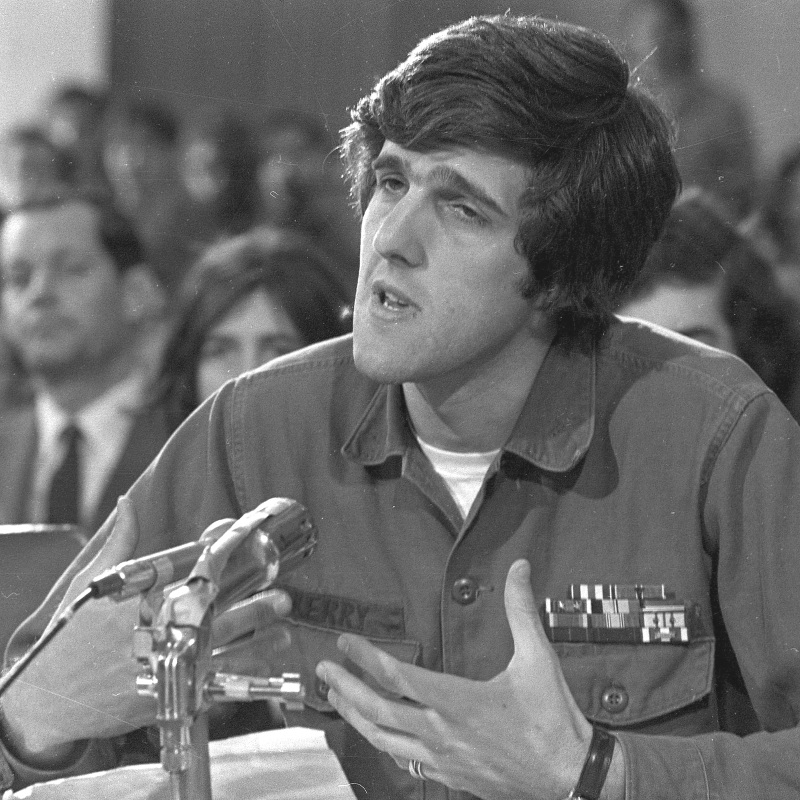

Then too there were protests the following year by “Vietnam Veterans Against the War,” including the testimony of 27-year-old Lieutenant John Kerry,* brought to Congress by Senator Ted Kennedy to describe the horrible behavior of fellow soldiers in Vietnam, aimed at the Nixon Administration’s refusal to simply abandon Vietnam − as if the Vietnam mess afflicting America was a Nixon rather than a Johnson political product.

At one point, Boomer New York Times journalists captured the attention of America with their front-page publication of sections of The Pentagon Papers, classified information as to how the Vietnam War got started up in the first place back in the 1960s. And here too, most interestingly, anger at the shocking D.C. political deception revealed in the publications was carefully aimed not at the former Johnson Administration but at the present Nixon Administration, as if it was Nixon, not Johnson, that was to blame for such governmental deception.

Nonetheless anti-war protests soon began to die away (including Congressional opposition) when it became quite apparent as to how strongly the American people supported Nixon’s Vietnam policies.

Diplomatic Realpolitik. In the meantime, Nixon, and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, played the Realpolitik (German: Political Realist) game of covering the American withdrawal from Vietnam with visits and meetings with the leadership of both Communist Russia and Communist China, offering better American diplomatic relations (“détente” or a backing down in tension) with them for the tradeoff of them then offering to not get further involved in the Vietnam dynamic. Actually, Communist China and Communist Vietnam already did not get along very well with each other, something Johnson had failed to take notice of in his decision to stop “the spread of Communism” in Asia. And Russia had been supplying only armaments to the North, but little else. The idea was that this could stop now that the war in Vietnam was most probably coming to an end.

Nixon and Kissinger in Moscow – 1972

In any case, very little of Nixon’s diplomatic opening to the Communist East (after a very closed diplomatic period during the Johnson years) was appreciated by the Democratic-Party-controlled Congress. But the American people took note, and were quite pleased with such developments.

The 1972 elections … and Watergate. Indeed, by the time Nixon found himself up for re-election in 1972, there was very little likelihood that the Democratic Party candidate, George McGovern, had much of a chance, despite all of the Boomer youth who turned out in support of their strongly Leftist hero. Indeed, Nixon gained the Republican Party’s biggest presidential win ever with 60.7% of the popular vote. And in the Electoral College vote, McGovern received only the votes of Massachusetts and D.C. But D.C. was always a highly Democratic Party constituency no matter who ran for office, the Democratic Party closely identified with the idea of “let the Washington bureaucracy take care of you even better than you can take care of yourselves,” and the D.C. bureaucracy very much in love with that role as national savior, and intending to keep things that way.

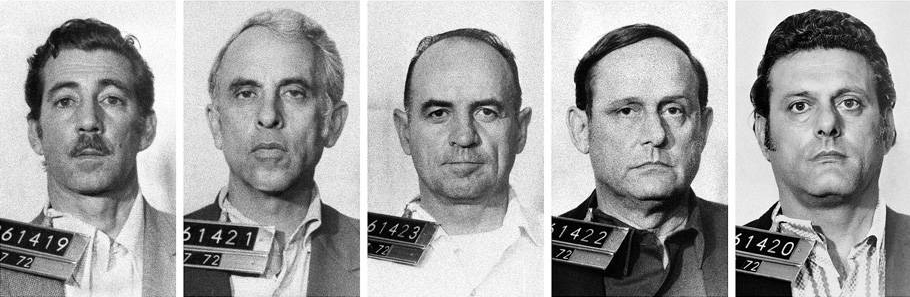

But political disaster would accompany this enormous Nixon victory, because of the unneeded antics of some of his campaign staff, who raided the Democratic Party offices at the Watergate Hotel in D.C., and got caught by the police in the process. They would go to jail.

But that was not what Nixon’s opponents wanted to see happen. They wanted Nixon himself to go to jail, even though it was never claimed that he himself ever authorized such shenanigans, only that he tried to cover up the political disaster after the fact.

Thus lengthy Watergate hearings got underway, and soon became the media’s preoccupation (actually from the very first days of Nixon’s second term in office.)

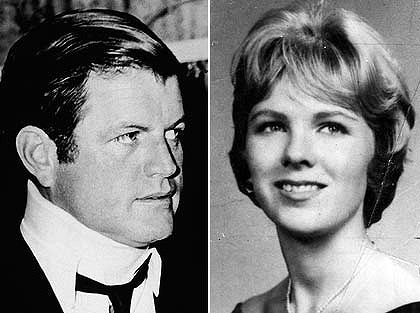

And most interestingly, setting up this inquiry in the U.S. Senate was Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, a man whose moral character was hardly any better than the man he was attacking.*

But things did not seem to be going against Nixon … until the event (October 1973) of Nixon getting special prosecutor Archibald Cox fired. Nixon was trying to block Cox’s efforts to get Nixon’s presidential tapes … which Nixon considered to be his own personal matter – but by which Nixon’s opponents hoped that Nixon’s exact involvement in the matter would be discovered.

Congress takes over American foreign policy. With Nixon now under full Congressional and media attack, Congress decided that it was time to take over much of what were constitutionally, or at least traditionally, presidential powers, domestically and internationally.

The Arab-Israeli October War. Thankfully Congress did not yet get involved in the huge crisis that broke out again (October 1973) in the constant struggle between Israel and its Arab neighbors, principally Egypt.

Egypt’s new president, Sadat, was deeply irritated with the Israeli seizure and shut down of the Suez Canal, and secretly worked with Syria’s president Assad to take on Israel in order to regain territory formerly lost to Israel. With a now well-trained army, Sadat suddenly sent his troops across the Suez Canal and succeeded in pushing the Israeli position back deeply, assisted by an Egyptian air force able to offer air support this time. But Israel managed to dig in and find a way to hold its position. Meanwhile, Assad struck in the north, but without any particular gain in the process. In fact, Israel quickly reversed the situation in the north, and began a strong push toward the Syrian capital, Damascus.

On the Egyptian front, however, the war quickly became one of military resupply, the Russians glad to send arms to Egypt, and Kissinger soon deciding to do the same for Israel, although America’s NATO allies wanted no part in any of this.

A U.S. C-5 Galaxy unloads an M-60 Patton tank at Ben Gurion International Airport during Operation Nickel Grass

Nonetheless, with the American resupply, the Israelis were able to retake their position, even cross the Suez Canal and entrap the Egyptian Army. The war was thus now over.

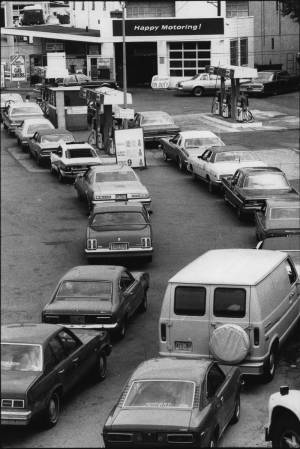

An international oil crisis. But ultimately the conflict itself was not over, when the Arab oil states of OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) cut back the flow of oil to punish the industrial West for its support of Israel. This quickly quadrupled the price of crude oil (from $3 to $12 a barrel), creating an energy shock across the world, including one that dug deep in America.

A gas shortage during the 1973 OPEC oil embargo imposed on the West for its support of Israel in the October 1973 Arab-Israeli or ‘Yom Kippur’ War

American oil reserves were hardly up to the challenge, and ultimately massive inflation hit America across all economic sectors (energy after all is needed everywhere). For Nixon, and America, there was not a lot to be done, except to try to move on as best possible.

Congress cuts back the president’s discretionary spending power. Meanwhile, on the domestic front, Congress decided that it was time to return the country to “democracy,” to get rid of the “authoritarianism” coming from the White House (strong executive power never seemed to bother these Liberals when it was Johnson using those powers). A big move in that direction came in 1974 with Congress ending the president’s discretionary spending powers, especially as Nixon had been using them to impound funds in order to cut back government overspending approved by Congress. But such spending was a big means of getting political support from strong players in the nation’s political game, and Congress did not want such funding blocked.

But then they made the mistake not only of stripping Nixon of a presidential power that reached back all the way to the days of Jefferson, they also set up the Congressional Budget Office to supervise government spending, not realizing that they were putting their own “pork barreling” or self-serving political spending in full public notice. Oops!

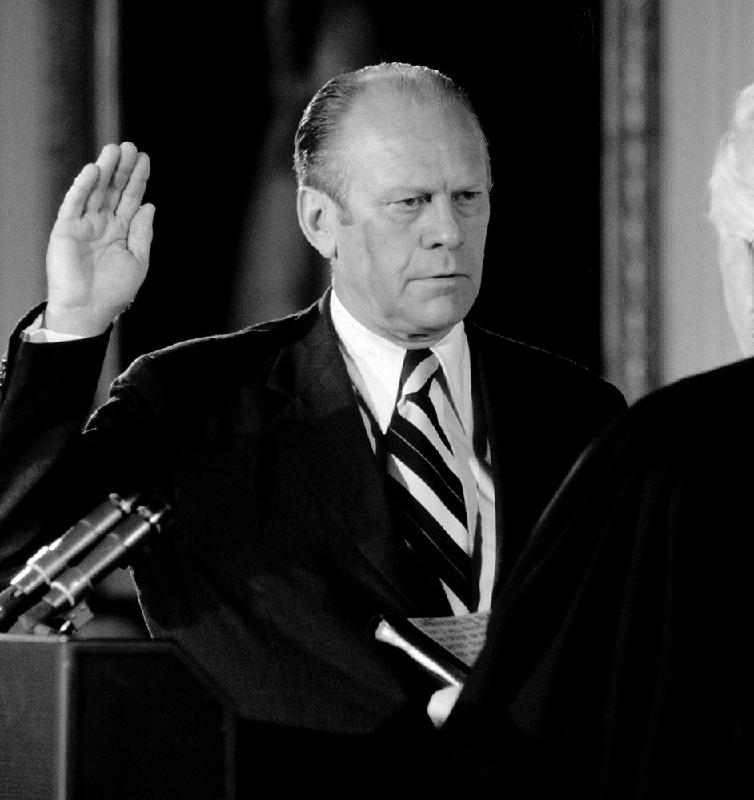

Nixon resigns (August 1974). Meanwhile Watergate dragged on, Congressional midterm elections were coming up, and things were not looking very good for the Republicans in Congress. And Nixon, sensing his political isolation (Congress was bent on impeaching and sentencing Nixon for whatever crime they could decide on), and seeing no way out of the mess, finally took the advice of Republican colleagues and simply resigned as president. Private citizen Nixon would now have to deal with the mess on his own.

Ford takes over at the White House. Replacing him was his vice president, former Republican congressional leader Gerald Ford, who himself had been elected to the vice-presidential office, not by the American people but by a special vote of Congress, when Nixon’s former Vice President, Spiro Agnew, was forced to resign over charges of corruption that occurred earlier during Agnew’s service as Maryland governor. Thus in short, though widely respected in Congress, Ford had no serious executive muscle that he would be able to use in the face of a very active Democrat Congress.

Ford being sworn in as U.S. president

But he did have one presidential power which, after deep prayer on the matter, he decided to use: the power to pardon Nixon, and thus help the nation to move on to other matters. Democrats were furious, because they were looking forward eagerly to a lynching they were hoping to conduct of the “evil Nixon.”

Disaster in Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, Congress had also taken over American foreign policy, ultimately creating a bloody mess in Southeast Asia as a result (never acknowledged by these congressmen themselves, however). First of all, during the Watergate hearings, Congress refused a request by Nixon to help the South Vietnamese government cover a not-huge financial shortfall created by the global energy inflation. Indeed, Congress even announced that it would be ending all financial support of the South Vietnamese government as of 1976. What was that all about? America supported a lot of its allies in their early days in order to get themselves up and running. Why quit on Vietnam? There was no good answer offered by Congress, because there was none. Was this just another jab designed to embarrass the president?

But unfortunately, the result of such Congressional blindness was far worse than this. The announced withdrawal of America’s Vietnamese support would, in early 1975, bring morale collapse on the part of the pro-Western parties defending and governing South Vietnam, and confidence to their old opponents. It would also bring massive destruction of Vietnamese lives at the hands of those enemies, particularly the massive imprisonment and death of those who had served alongside America during those many years. How thoughtless, how cruel, it was of Congress to needlessly abandon its Vietnamese friends. But Congress offered no explanation for such political blindness.

Desperate Vietnamese trying to escape Saigon with the departing Americans – April 29, 1975

But the tragedy immediately spilled next door, when Cambodian Communists (The “Khmer Rouge”) under Pol Pot felt that they now had the go-ahead to do their own political cleansing, by treating every urban Cambodian as a potential enemy (the Khmer Rouge had taken on Mao’s “rural” rather than “urban” ideological instincts). Countless numbers (millions?) of Cambodians were “liquidated,” while the world looked on in horror, unable to do anything about the “Cambodian Killing Fields” because the leader of the Western World (America) had become paralyzed by its own stupid infighting.

Phnom Penh – Khmer Rouge attacking the capital where over a million people had sought refuge … at the same time that the Vietnamese Communists were about to overrun Saigon.

The 1976 Bi-Centennial. 1976 was supposed to be a year of great celebration, marking 200 years since the event initiating the full independence of America from British rule. Americans gave the event a good try, though it never really felt right. America was deeply wounded by all the political goings-on, both at home and abroad. Something was wrong in America, deeply wrong.

The moral assault on Middle America. On a number of social fronts America was changing, changing rapidly. Quite noticeably was the changing place of the American family itself in the scheme of things. Homelife was slipping into the status of being merely supportive of the more important professional life that young Americans were chasing after, rather than the reverse, which had been the case for previous American generations when jobs were there mostly just to support the means of a family to go about its all-important homelife. With the rise of the Boomers to adulthood, with their instinct for self-service in all things, male-female relations often were no more than just sexual alliances … for the time being. Indeed, divorce rates were climbing, and climbing rapidly. Thus also, an increasing number of children – ones who had not been aborted as a result of an unintended Boomer pregnancy – were finding themselves raised by single parents, making for some confusion when mostly male role models were missing.

For the Black world this became deeply problematic as Black women felt they fared better under governmental assistance offered when no male was around to support the family (but of course were needed briefly to help produce those babies that brought in such government assistance). Thus the once strong Black family system simply broke down under the rising government-welfare system.

Sexual roles themselves were undergoing changes. Since Betty Friedan’s widely-popular book, The Feminine Mystique, hit the press in 1963, the role of a woman as housewife and mother became regarded by many young women as a very secondary matter, if not even a very poor choice, when a better world awaited them in taking on the same roles that men had long played in the professional world. For Boomer girls, Friedan’s book became something of a Bible, shaping the thinking that would become the very heart of the day’s feminism.

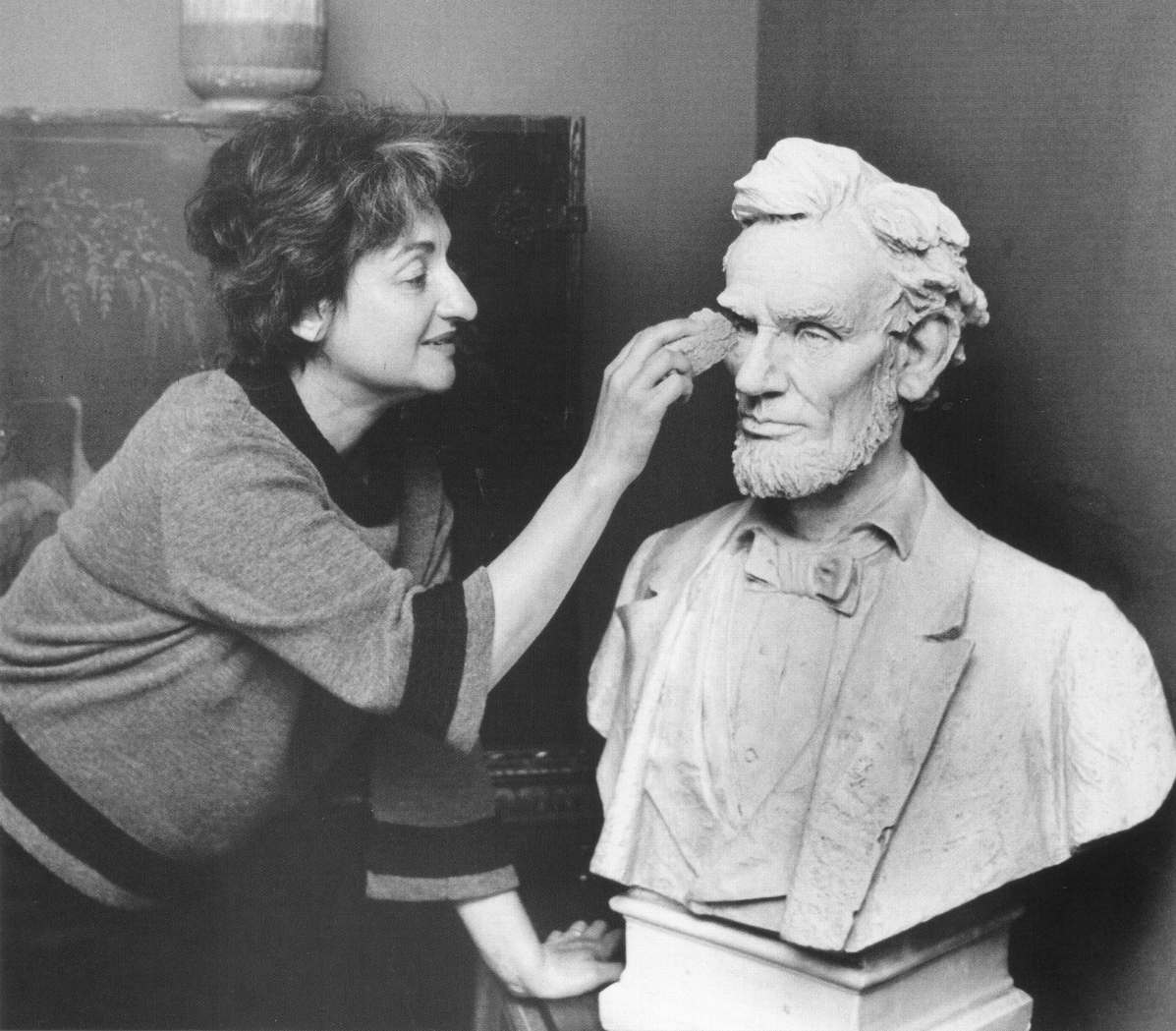

Betty Friedan meets Lincoln!

As for men, nothing of a similar counsel was offered to them as to what they were to do in this changing world. While the idea was growing rapidly that there was something very special in being a woman, there now seemed nothing very special about being a male. Indeed, men were instructed to back off, and let the women have their own place in the scheme of things. Not surprisingly, since 1979, there have been more women than men going to college to get a higher education.*

The Supreme Court takes the political lead. And all this change did not come just by way of a general moral drift. It was promoted very strongly by political voices, not only in Congress but even (and most importantly) on the Supreme Court. The Court always seemed to see itself as taking the higher moral road than the one taken by the American citizenry itself.

For instance, at the time, desegregation was certainly well underway across America, but not proceeding at the speed that the Court felt it should. Thus the Supreme Court felt that it was its moral duty to take charge of this program, deciding how the school desegregation was to proceed, with several cases involved (1968, 1969, and 1971). The Court ultimately required specific proportions of Black/White children’s school attendance and also a specific ratio of Black/White hiring of teachers. And precise school busing programs to bring about just such proportional school attendance were also taken up by federal district judges, under the guidance of standards set out by the Supreme Court.

Then there was the Supreme Court 8-1 decision in the 1971 Lemon v. Kurtzman case, in which the Court took on the assumption that education is a federal governmental matter, not a family or local school board matter.

The Burger Court

In doing so, the Court declared that only things that serve a purely secular purpose can be used in public support of the education of America’s children. There must not be “excessive government entanglement” with religion … meaning religion – excepting the religion of Secularism and its religious colleague Humanism, of course – is to be kept out of American public education. For a society that was founded, developed, and succeeded splendidly as a Christian society, this was a huge interference of the Court in American society’s social-moral foundations.

Then there was the Roe v. Wade decision by that court in 1973 concerning the matter of abortion. The killing of children historically has varied widely, Romans allowed to do so up to a child’s seventh year, Muslims required to do so at any age if a son or daughter has violated a sexual taboo. But Christians and Jews have long held that the killing of a child, even one still in the womb, is in violation of God’s sovereign rule over us all, from the movement of conception onward.* Thus states across the country made abortion quite illegal. But with the rapid expansion of Boomer “sexual freedom,” unwanted pregnancies abounded, and pressure from the political Left mounted to get rid of those restrictions. Thus a challenge to Texas’s anti-abortion laws made its way to the Supreme Court. And there the Court laid out a very precise ruling on how varying rights to abortion were permissible under different trimesters of pregnancy. And this then would be the law of the land, overriding all state laws, as the Supreme Court took upon itself the right to decree such national law.

But taking these matters out of the hands of the Americans themselves merely constituted legislation by judicial decree. Of course, this is hardly “democracy,” where the people themselves (under inspired leadership, of course) take on the responsibility of meeting a society’s challenges. What the Supreme Court was doing was simply political authoritarianism in which those in power themselves take up just those responsibilities, such authority always justified, of course, along some kind of moral line or other.

Most interestingly this is why the ACLU brings its political crusades to the Supreme Court, not to Congress. They need only a handful of lawyers in black robes to see things in accordance with the “Liberal” worldview of the ACLU in order to get that worldview dictated to the rest of us. So much for the “civil liberties” they claim that they are all about.

CARTER’S MORE MORAL AMERICA

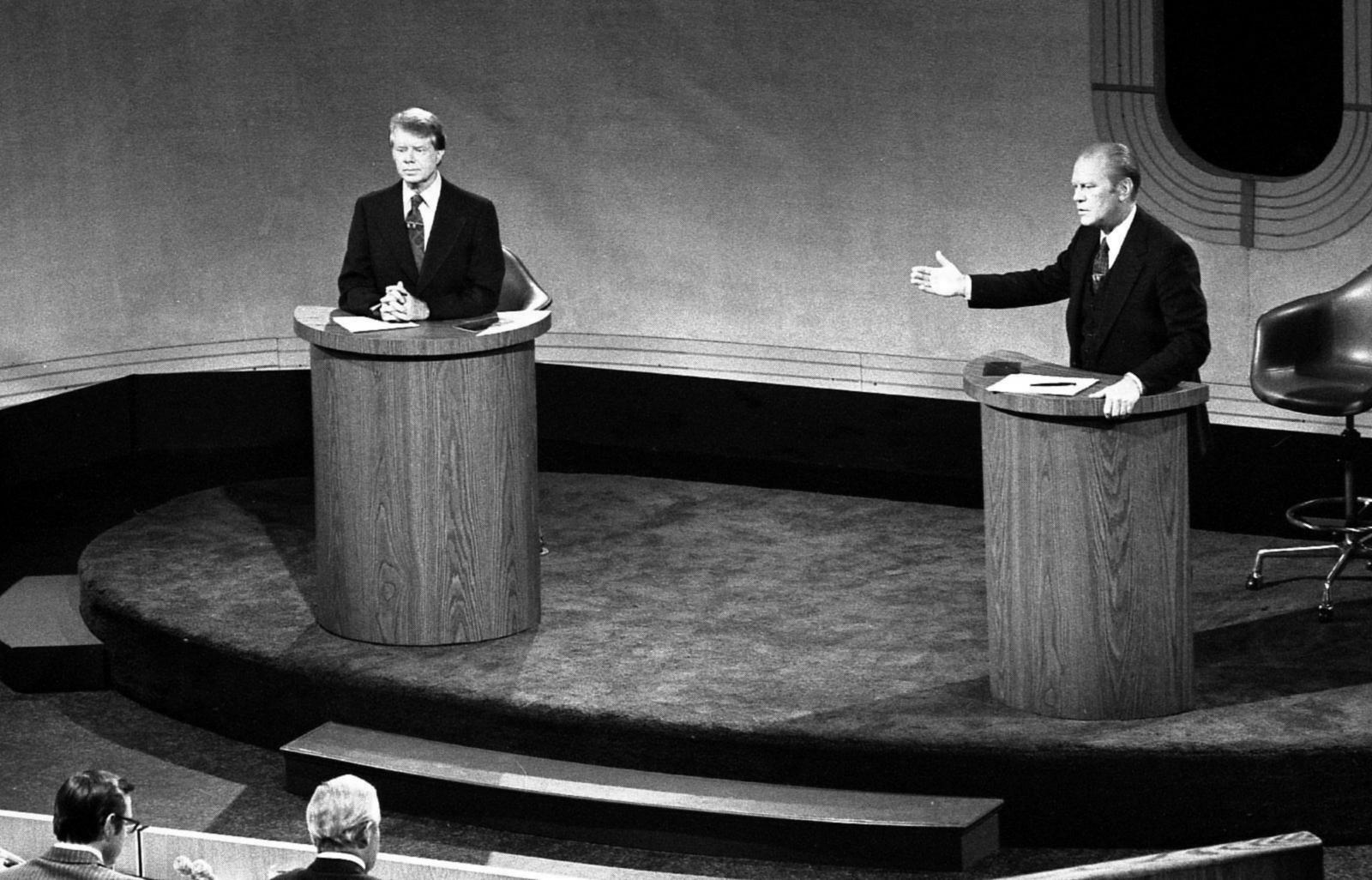

The 1976 national elections unsurprisingly seemed to hinge on the matter of morality in American politics. The Republican candidate, Ford, was highly respected in this matter by his congressional colleagues. But he was also, in the American mind, somewhat connected with the deeply discredited Nixon legacy. The Democrats had no national figure to offer, Ted Kennedy being the Democrat of national recognition, but his own running for the presidency likely to bring up the embarrassing matter of Chappaquiddick. Thus, to the surprise of many, the Democrats chose a former governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, as their presidential candidate. Carter of course had recently been building up contacts within the upper circles of the Democratic Party. But he was otherwise unknown outside of those circles.

But he had the presidential debates in which to present his political-moral credentials to the American people.* In those debates, he criticized Ford for having practiced the “non-moral” practice of Realpolitik, using power tradeoff simply to get political gains, quite apart from whether they were the moral thing to do or not. For Carter, the Cold War was over, and America needed to be engaged in no such power games. Thus he proposed even pulling American troops out of NATO, no longer needed in this postwar era. Also, in pursuing his “more moral” foreign policy, if president he would end America’s support of dictators. Indeed, he would even force America’s allies Iran and South Korea to liberalize or lose American support.

Somehow he was thus able to impress the American voter to the point that he won, 50.1 percent of the vote to Ford’s 48.0 percent.

Carter’s “more moral” foreign policy

The surrender of the Panama Canal. But his “more moral” foreign policy came into serious question when soon in office Carter proposed to “give back” the Panama Canal to Panama, agreeing in a meeting with Panamanian dictator Omar Torrijos to set in place a schedule for just such a surrender of American sovereignty over its canal to Panama in future stages or steps. Why Carter felt that this was necessary to do so, he never really fully explained. What was he trying to gain in doing so? And why was he so supportive of a Panamanian dictator?

Carter and Torrijos – September 1977

Carter backs off a bit. Actually, Carter also fairly quickly came to back off on his moral rhetoric when it was pointed out to him how strategically valuable America’s relationship with both South Korea and Iran happened to be. Indeed, Russia had taken his pronouncements as an opportunity to increase Russian support of the anti-Shah voices in Iran, individuals that the Shah had just released from prison under the fear of losing American support if he did not do so. Clearly Russia was once again looking for the opportunity to use a pro-Soviet Iran to finally get a strategic position at the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. The Russians were already engaged in just such political maneuvering in Afghanistan.

Serious problems develop in Iran. So Carter backed off from his anti-Shah talk, and in a visit abroad (late 1977) which included Iran, spoke glowingly about America’s long relationship with Iran. This prompted the Shah to try to tighten back up again on his opposition. But by this time, the opposition was organizing so well that the Shah’s opponents now simply rose up in protest, beginning serious troubles for the Shah, troubles which Iranian intelligence services made sure that Carter was unaware of. Things thus grew crazier in Iran.

For instance, unemployment among Western-educated young adults was high, the need for engineers in a very simple oil-exporting economy being very low. Unsurprisingly, many of these proto-Westerners would become serious participants in the anti-Shah movement.

Iranian students in full rebellion against the Shah’s government – 1978

But even more serious were the number of rural Iranians, once deeply appreciative of the way the Shah brought roads and public services to their communities. But since the oil inflation of 1973, they had suffered economically deeply, having to pay vastly higher prices for energy and fertilizers, but finding their products not keeping up with such inflation because of the global market keeping agricultural pricing rather steady. Consequently, these conservative Iranian farmers were growing increasingly bitter, even “anti-Western” in how they were coming to view larger social dynamics. And the Shah would become the object of that bitterness, as if it were his duty to solve this complex marketing issue.

But Carter was largely unaware of these developments.

Carter presses for an Egyptian-Israeli accord. Nonetheless Carter proved to be actually quite the practitioner of Realpolitik when he came to the rescue of Egyptian president Sadat, who had, at the potential loss of political support at home in Egypt by doing so, gone to Israel and proposed to the Israelis a new positive relationship. Egypt would be willing to be the first Arab nation to “recognize” Israel, if the Israelis were willing to make some concessions, in particular, in stepping back from their grip on the Suez Canal so that the canal could be reopened (and Egypt get the revenue from it that it so badly needed). But Sadat also wanted to see the return of the West bank territory to the Palestinians. Both matters indeed had already been insisted on by the U.N.

But at first Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin seemed uninterested in the deal. This led Carter to step forward in 1978 and offer Begin the “opportunity” (Carter pressure) to come to Camp David in Maryland and meet with Sadat, and work out just such an arrangement. Begin agreed, but at the meeting dragged his feet. Carter then intervened personally, and finally got the agreement that was the supposed purpose of the meeting. That was quite an achievement, which even led the Nobel committee to award the next Nobel Peace Prize to both Begin and Sadat (which actually should have included Carter!).

Sadat, Carter, and Begin at the White House – 1978

The end of the Shah’s government. Most tragically, at this point things were falling apart in Iran. The anti-Shah street protesting was so extensive that finally, in January of 1979, the Shah left Iran. The rebels were thrilled.

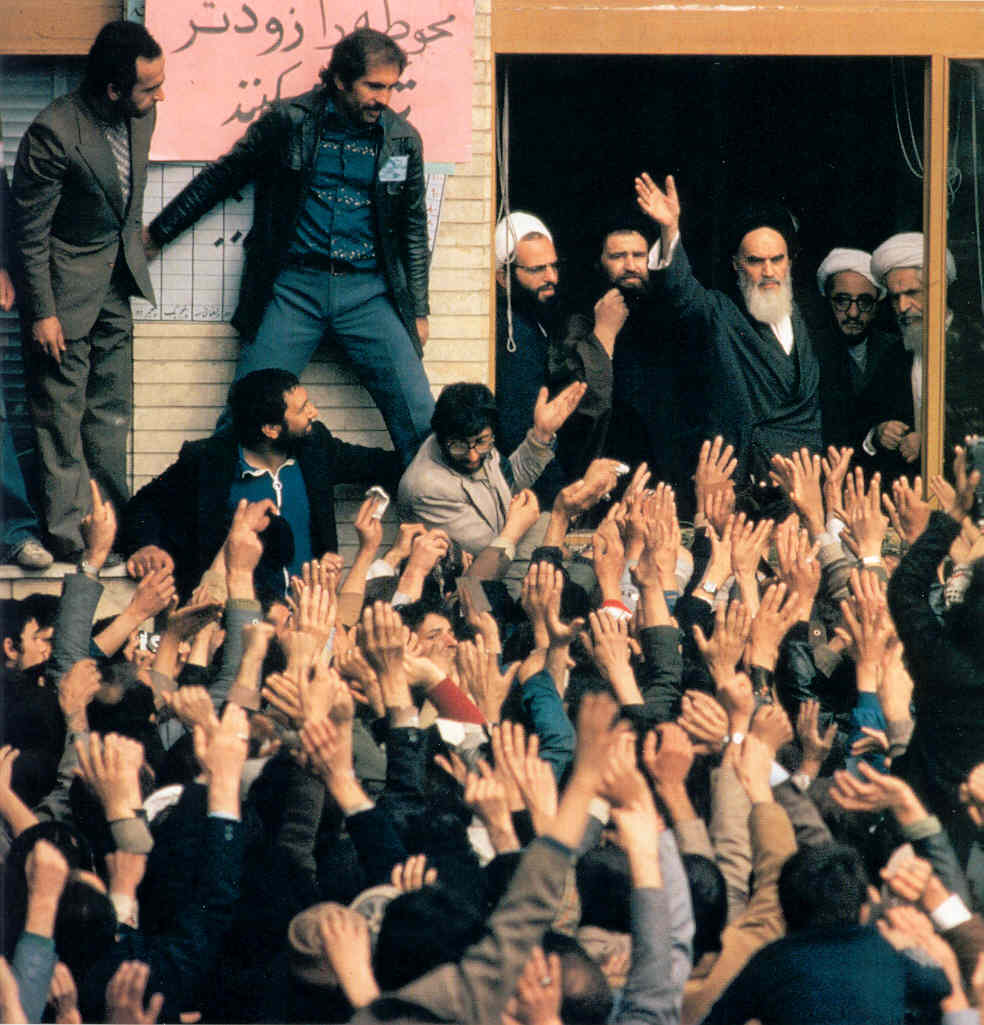

But the game was not over. The matter of who then was in charge of Iran was not yet decided. That however would be quickly resolved when in February the Ayatollah (Muslim ruler) Khomeini flew in from his exile in Paris and was greeted as Iran’s liberator. It was thus decided that Iran would now honor not new Western political ways (desired by many of the protesters) but very traditional Muslim ways (desired not only by Iran’s conservative farmers but also by a huge part of capital-city Tehran’s population).

Ayatollah Khomeini greeted by enthusiastic Iranians – February 1979

And it would all soon be conducted under the slogan “Death to America,” as if America was the evil genius behind Iran’s complex problems.

And what could Carter do at this point about this crisis in the Middle East? Absolutely nothing.

Hope, and then confusion, even catastrophe. On the other hand, détente with both China and Russia, begun under Nixon, would continue under Carter, when that same January (1979) Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping came to Washington to sign new diplomatic accords, ones leading to America’s formal recognition of China, and in June, Carter and Russian leader Brezhnev met in Vienna to sign an updated SALT (Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty), in which both parties agreed on a self-limitation of nuclear weapons development.

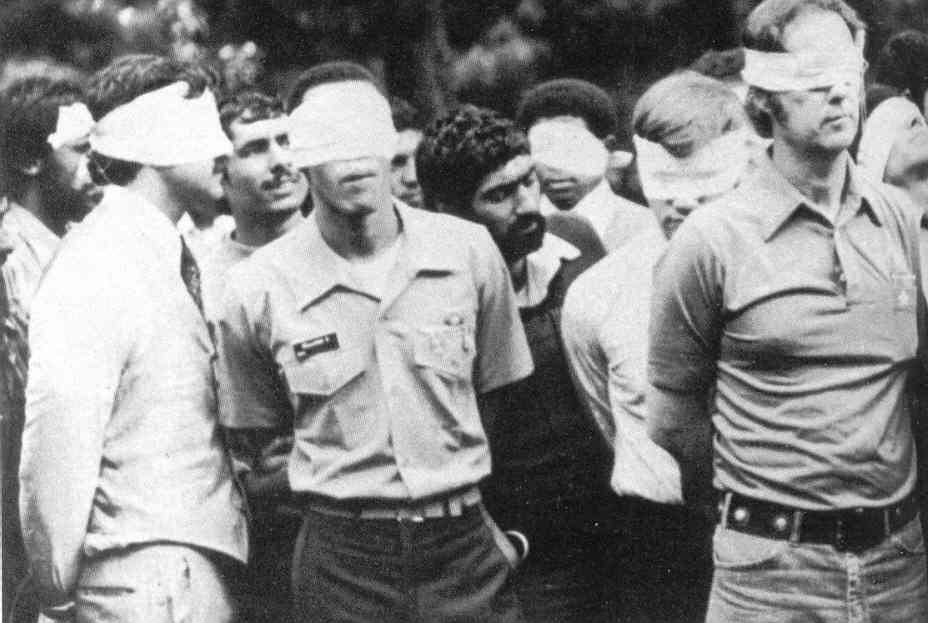

But 1979 would turn horrible by the end of the year, on a number of fronts. When in October the Shah found himself suffering from cancer, and Carter proposed to bring him to America for treatment, young Muslim militants (the Iranian Revolutionary Guard) were so incensed that they invaded the American embassy in Tehran, seized, bound and then dragged before an angry crowd its employees, and then held them in captivity, and would continue to do so until early 1981.

Meanwhile, nearby in Afghanistan, Russian Communist-puppets that successively took command of Afghanistan (since April 1978) were making a cruel mess of the country, causing Muslim Afghani fighters (mujahideen) to organize into strong resistance groups, with Carter secretly sending aid to these mujahideen. Finally (December 1979) the Russians decided to take control of matters there directly, sending thousands of Russian troops into the country. But Carter took deep exception to this Russian invasion, denouncing the act loudly and ending his move to get SALT II approved by the Senate.

Even worse, the Olympic Games were due to take place in Moscow the coming July of 1980, and Carter promised that America would not be participating if the Russians did not pull out of Afghanistan. Russia saw no way that it could back out of its huge military commitment. And thus hundreds of young American athletes were to find that everything they had been training for would not be coming their way. This ultimately made no one happy.

Then a huge blunder for Carter would occur in 1980 when in April he sent special forces to Iran with the intention of rescuing the American hostages from Iranian hands. The whole thing ended in a sandstorm disaster just inside Iran, and the operation had to be called off, with the serious loss of life and helicopters. Carter sadly would have to tell America of his latest setback.

It was an election year, and Carter was not looking good for re-election. Even Ted Kennedy saw himself as the possible candidate and became loudly critical of Carter’s presidency. In the end, Carter would get the Democratic Party nomination again. But it would be an uphill battle.

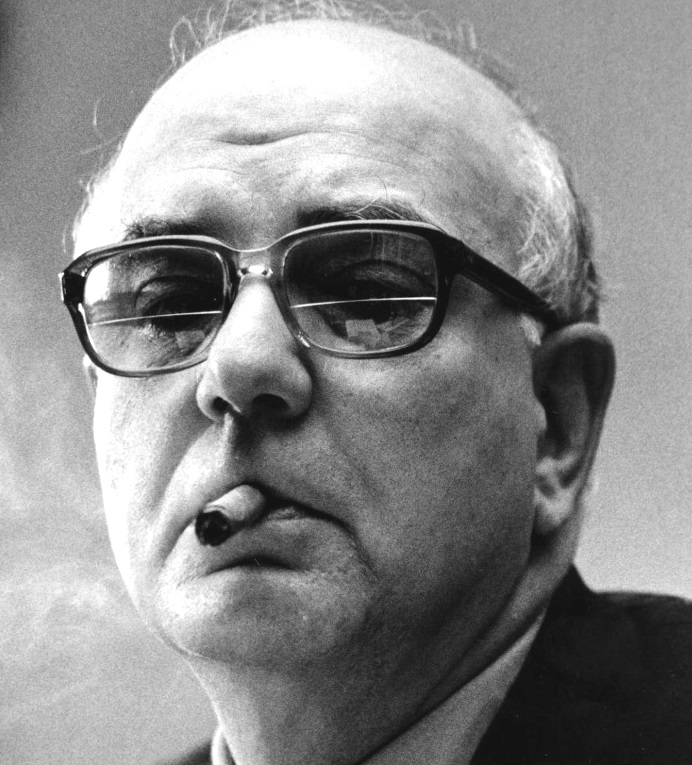

Volcker, and economic disaster at home. Besides these humiliations, the biggest problem facing Carter was America’s “economic czar,” Federal Reserve System Board Governor Paul Volcker, who hit America with what came to be termed the “Volcker Shock.” With the fall of the Shah, oil prices had once again shot up, way up (quadrupled), causing energy costs (involved in almost every economic enterprise) to skyrocket. To cover those costs, producers had to raise their product prices, also at a high rate.

Volcker, and economic disaster at home. Besides these humiliations, the biggest problem facing Carter was America’s “economic czar,” Federal Reserve System Board Governor Paul Volcker, who hit America with what came to be termed the “Volcker Shock.” With the fall of the Shah, oil prices had once again shot up, way up (quadrupled), causing energy costs (involved in almost every economic enterprise) to skyrocket. To cover those costs, producers had to raise their product prices, also at a high rate.

Most tragically, for reasons that in fact defy all good reason, Volcker decided that he would unilaterally fight such inflation with his own high-interest rate strategy. In other words, federal interest rates set by the Federal Reserve would be passed on to banking corporations that depended on federal backing. These rates would then be passed on to a bank’s customer for their bank loans (all industrial production depends deeply on just such commercial financing), interest rates skyrocketing from a normal 6 percent almost overnight to well above 20 percent.

In short, just to stay in business, industrial producers would have to raise their prices to meet not only higher energy costs, they would now also have to now increase those prices to cover their higher interest rate costs. So, in fact, Volcker’s strategy forced prices further upward, not downward. What was he thinking?

The only possibility was that he was trying to design a new Depression, because the closing down of production (and the letting off of workers) would eventually bring down prices, if producers were to stay in business at all. Industrial customers would now be vastly poorer and thus be unable to meet high prices. Those prices would therefore have to come down if those products were to move at all, although this would bring them no profit in their operations.

However, at this point, producers would typically just choose to shut down, to close shop. They are, after all, in business to make money, not lose money.

Consequently, Volcker helped throw America into deep, deep recession, making America very bitter, that bitterness aimed not at Volcker (who was not “democratically” selected in the first place) but at the person who appointed him, Carter. Carter would pay dearly for the horrible economic condition that America suffered under as it went to the polls in 1980.

The 1980 elections. Indeed, the Republicans would do quite nicely in the national elections that year, the Republican nominee Ronald Reagan gaining 50.7 percent of the popular vote and 489 electoral college votes, with Carter receiving only 41 percent of the popular vote and only 49 electoral college votes, the balance of the popular vote (6.6 percent) going to the Liberal Illinois Republican congressman John Anderson, at that point running as an Independent (gaining no electoral college votes). A deeply discouraged America was ready to move on under new leadership.

Go on to the next section:

The Sole Superpower