CHAPTER NINE

THE COLD WAR INTENSIFIES

THE KOREAN WAR (1950-1953)

In June of 1950, without any warning, North Korea invaded South Korea, and very quickly nearly wiped out all South Korean resistance, before Truman could also quite quickly move American troops from Japan to South Korea, and save that country from Kim Il Sung’s Russian-backed North Korean Communist takeover of the whole of Korea. It would take nearly three years of effort to bring things back approximately to where the former “temporary” border dividing North and South Korea happened to be. And for America, this Korean War would prove to be a major engagement, clarifying even further the battle between the “Free West” and the always threatening realm of international Communism.

In the war itself, Truman was able to get U.N. backing − so that the troops supporting South Korea were actually termed “U.N. troops” … for indeed, they included troops from other nations as well. And Truman was able to do this because Russia had been boycotting U.N. meetings because of its anger over America’s refusal to turn the China seat on the Security Council over to Mao’s officials. Thus Russia was not there to veto Truman’s troop proposal. They would never make this mistake again.

The U.N. troops pushed the line of battle back north, particularly after MacArthur, commanding the U.N. troops, was able to offload troops on the shores behind the North Korean troops, panicking the latter, and sending them fleeing back into the North.

American troops retake South Korea’s capital city Seoul – September 1950

Now political and strategic problems set in on the “U.N.” side as the American troops reached north near the Chinese border, and MacArthur got himself before an adoring press and spoke openly of the idea of invading China itself and liberating that country from Communist rule. Truman was furious … because MacArthur not only had not run any of this by Truman as U.S. Commander-in-chief, strategically the idea was horrible. A war with China would have been all-absorbing, and thus highly distracting of the problem of Soviet Russian interests in West Europe, a much greater priority in terms of American national interests. But MacArthur, always Asian-focused in his personal interests, was completely blinded by this diplomatic matter … and also amazingly blind to the buildup of some 300,000 Chinese troops at the Korean border, ready to attack an American force in North Korea one-tenth that size.

And thus, not wanting to see what was going to develop in the Truman-MacArthur debate (Truman removed MacArthur from command), Mao had his “volunteer” (not “official”) troops invade Korea, and quickly drive the U.N. troops back south.

American forces retreat from Chosin Reservoir

in the face of the massive Chinese assault – December 1950

But things seem to stall around the former North-South border, and the war simply settled into some kind of stalemate along those lines. Armistice negotiations then got started between the two sides, though nothing happened immediately. In fact it would take two more years until in 1953 an armistice was finally agreed on. At that point the Korean War was over, though the tensions between the two sides would remain.

Armistice negotiations began in 1951 … but dragged on until 1953

THE COLD WAR SHAPES AMERICA ITSELF

The hunt for Communists at home

With this huge concern about authoritarian Communism abroad, it was inevitable that this would also raise a similar concern about just how deeply such an evil philosophy had made its way into American society as well. This concern was focused in particular on groups and individuals that moved – or at least previously had moved – along Communist or even just Socialist ideological lines. True, the war, and developments since the war, backed a lot of these individuals and groups away from their former “Leftist” tendencies. But it would be very hard for them to live down what they had once been. Fiercely anti-Communist Americans were not easily forgiving on such matters.

But this, in turn, annoyed many American intellectuals greatly, because of what they considered to be a most unfair suspicion they found themselves to be under. And such annoyance would soon turn to a spirit of vengeance, separating the “Middle America” of the Vets from the “Enlightened America” of the intellectual world, a group I term “Intellectual America.” Consequently, this split would soon enough turn very ugly.

HUAC’s investigations. Not helping matters at all was what Congress was discovering to be treasonous behavior on the part of members of that “higher” American social circle. Congress’s House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was deeply involved in the investigation of exactly how intimately involved American political leadership had become during their wartime alliance with Stalin. It seems that many, such as Roosevelt’s “Ware group,” had proven to be a bit too pro-Stalin in their behavior. According to Congressman Richard Nixon’s investigation into the matter, they actually committed very serious treason by passing strategic information on to Stalin.

When in 1948 Nixon turned on the socially elite Alger Hiss as being part of that spy network, on the basis of evidence offered by Hiss’s former Communist colleague Whittaker Chambers, the intellectual world was furious. They would hate Nixon for his role in the Hiss investigation, and continue to hold that hate for him, even when he was American president some quarter of a century later.

Alger Hiss taking the oath before a hearing – 1948

Orwell’s 1984. The situation became even more tense when the 1949 publication of George Orwell’s book 1984 hit the American bestselling list. It was a terrifying story about how in the future (1984) “Big Brother,” an authoritarian individual like Hitler or Stalin, will have managed to take total control of society. The book was something of a warning that “totalitarianism” awaited people in the future, the way this monster was so easily able to control the very thoughts and actions of the people, so as to lure them into becoming members of a slave society. It all seemed so real to Americans that this was where history was headed … under the guise of very clever individuals able to seduce others into believing their political cause was necessary for the good of society.

Scientist spies. Then too, there was the discovery in 1951 of how a number of young Cambridge University-trained intellectuals had betrayed their British nation by serving as Stalinist spies high up in the British government.

And around that same time the discovery was made that a German, Claus Fuchs, working on the American nuclear program, was also spying for the Russians. He confessed, and then pointed the finger at others involved in similar spying, among them a husband-wife couple, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg … the Rosenbergs, however, claiming complete innocence. Outraged Intellectualist circles were quick to come to their defense as this all being wrongful condemnation of an innocent couple.*

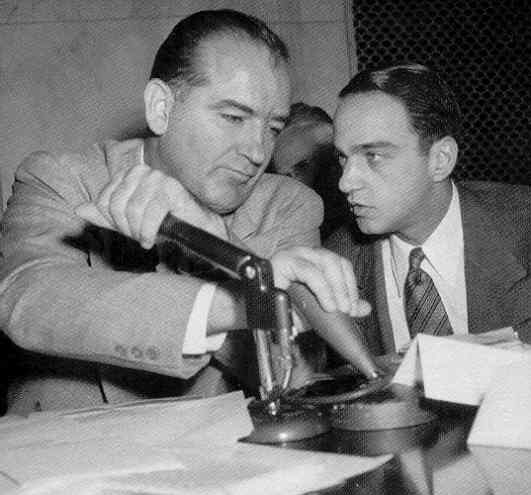

McCarthy. And then there was Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, who in 1950 began his own Senate investigation into such matters … in order to advance his own political career. Not having serious evidence to offer, over the next years he simply made things up as he went along, destroying careers, frightening Middle Americans even more about Communist conspiracy everywhere, and Intellectual America into full hostility to him … and to the Middle America supposedly backing him.

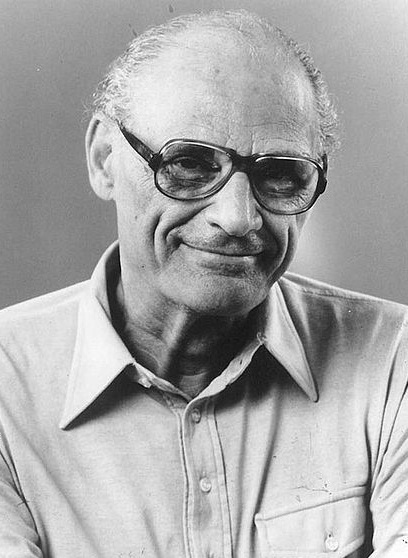

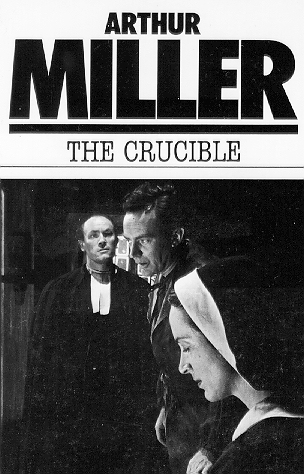

Miller’s The Crucible. Intellectual America then subtly struck back in 1953 with Arthur Miller’s Broadway play, The Crucible, a barely disguised anti-Middle-American plot, implying the connection between the present situation in America and the horrible conditions in the late 1600s when the Middle American “Puritans” of those day went on a murderous witch hunt. The play did not do particularly well in the 1950s. But it would be brought back into action in the 1960s, and become part of the required educational reading of American youth from that point on. With that, Intellectual America was beginning to get its payback!

Miller’s The Crucible. Intellectual America then subtly struck back in 1953 with Arthur Miller’s Broadway play, The Crucible, a barely disguised anti-Middle-American plot, implying the connection between the present situation in America and the horrible conditions in the late 1600s when the Middle American “Puritans” of those day went on a murderous witch hunt. The play did not do particularly well in the 1950s. But it would be brought back into action in the 1960s, and become part of the required educational reading of American youth from that point on. With that, Intellectual America was beginning to get its payback!

The development of the rising Boomer generation

Because of all this fear of authoritarianism, even totalitarianism, the Vets had been careful to teach their children to challenge all voices of authority. By the mid-1950s, these “Boomers” (born of the postwar “baby boom”) were now old enough to understand the vital importance of doing their own thinking – thinking as they supposedly were most “naturally” inclined to do. The assumption was that by their own natural instincts, they would grow up automatically holding the same worldview and social behavior patterns their parents lived by.

But that was a terrible misunderstanding, namely that the Vets’ own highly disciplined social-moral-spiritual instincts had come quite naturally to them. What they did not realize was how much the social discipline required by both the Depression and World War Two had shaped their lives. There was nothing “natural” about any of that.

So sadly, their Boomer offspring would grow up believing that their American world – which by the mid-1950s was indeed a comparatively carefree world – existed simply as a purely natural matter. Any attempt to bring that world under some kind of larger social authority was nothing more than authoritarianism … which it was their duty as good Americans to fight. In short, they were to fight all forms of social authority.

Tragically, the Vets had no idea that they were creating a monster generation − one that, upon arriving at adulthood (beginning around the mid-1960s), would find it impossible to respond to any social dynamic other than what they individually and quite personally judged to be “right,” to be “true,” all according to standards of their own choosing, whatever that might happen to be. And that might happen to be most anything, especially if other Boomers around them were holding themselves to such “non-standard” standards!

So it was that “personal freedom” rather than “personal service” would characterize how the Boomers would come to understand life, and how they would expect life to serve them. And such freedom would come to mean no moral boundaries, no moral imperatives, at least none of those held by their Vet parents. Indeed, such moral standards were to be challenged at every opportunity, in order for the Boomer to demonstrate exactly how free he or she was indeed!

Also, their Christianity would fade away as these Boomers became adults, because unlike their Vet parents, their deeper faith or worldview was shaped by seemingly “regular” or “natural” developments, ones that needed no hand of God to clear the path ahead. Boomers could do all of that themselves under their own personal rational powers.

And beginning in the mid-1960s, as the first of their generation reached college age, they would have agnostic or even atheistic mentors of Intellectual America (college professors, authors, “progressive” political figures) to support them in such thinking.

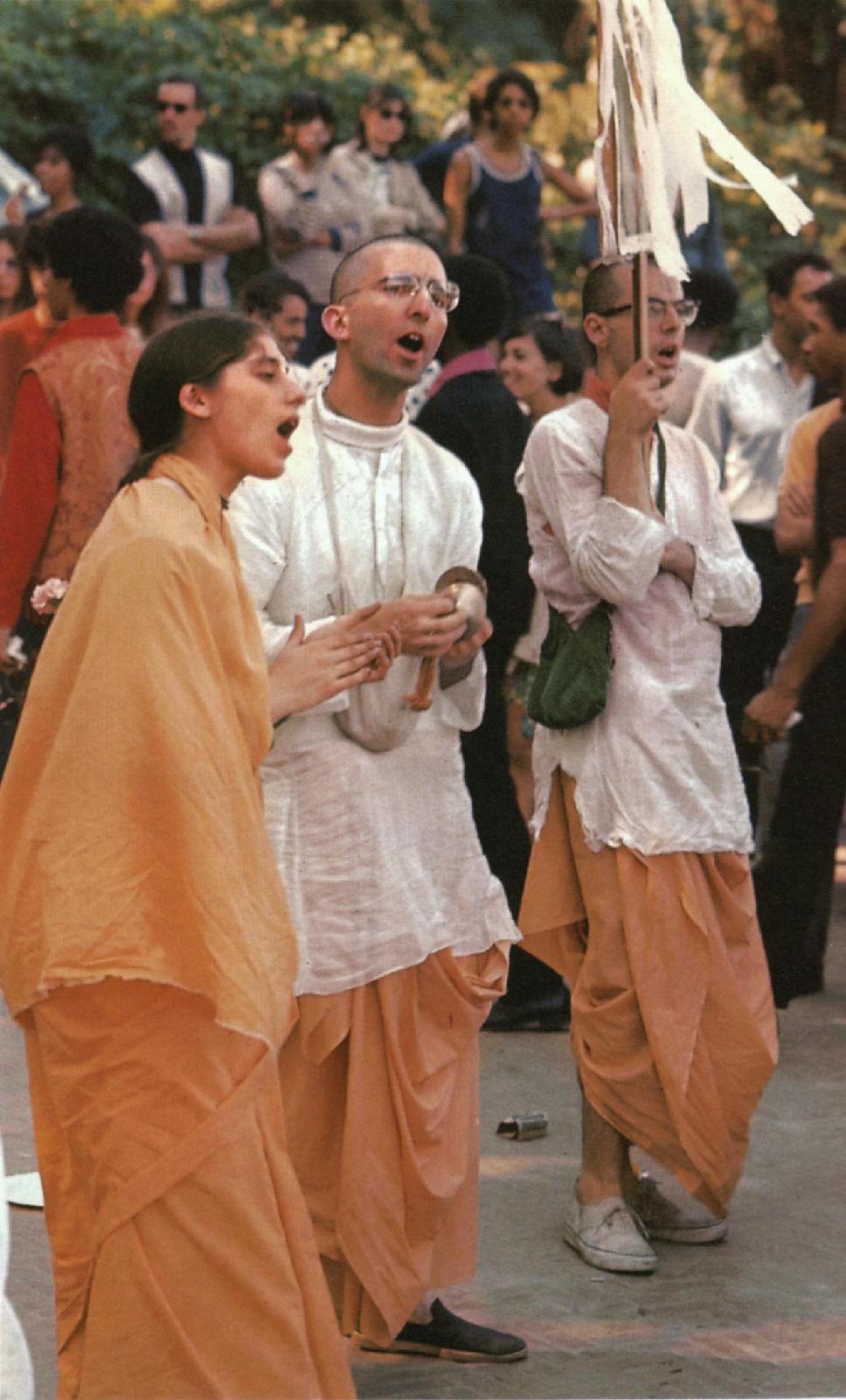

Sadly, all of this would leave them quite empty spiritually as social creatures. Ultimately, they would satisfy their instinctive social hunger by taking up “group-think,” by falling in line with the thought patterns of the social world they identified themselves with (namely, fellow Boomers). In short, although they believed themselves to be great independent thinkers, they would fall into group thinking, as easily as German youth in the 1930s had given themselves over to “Hitler think.”

Thus in interesting ways, the “me culture” of the Jazz Age of the Roaring Twenties would find itself going in full force again in America when these Baby Boomers began to hit adulthood in the mid-1960s. And it would produce a veritable social revolution. But more about all of that later.

Boomers giving expression to their free spirits – as Hare Krishna devotees – later-1960s

Christianity as America’s ongoing moral-spiritual foundation

On the other hand, the rigors of the Second World War and now the Cold War kept the Vets’ Middle America quite close to God, with Americans, through the rest of the 1940s and then through the 1950s, looking to God for his support and guidance in these still very challenging times.

In something of a contrast to “Christian Europe,” which felt let down by a God who seemed to fall silent when they fell victim to the Nazi horror, and now while facing a monstrous Communist threat, Americans were quite certain that it was their very strong faith in God (and certainly not Human Reason) that had directed their very productive, very successful efforts during the recent war, and was continuing to do so now that America found itself at the top of things as the protector of the “Free World.”

Thus Vereide’s prayer breakfast movement continued after the war to be very popular among leaders across the nation, Congress in 1953 ultimately authorizing the National Prayer Breakfast in Washington to be held annually each February (as indeed it has been ever since then).

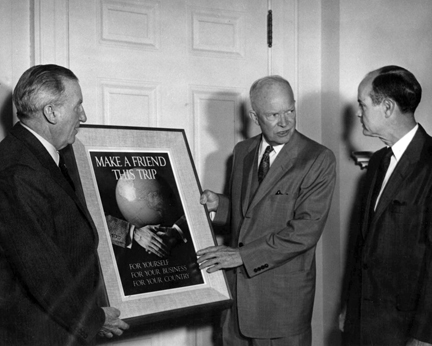

Eisenhower with Vereide (on the left) – 1953

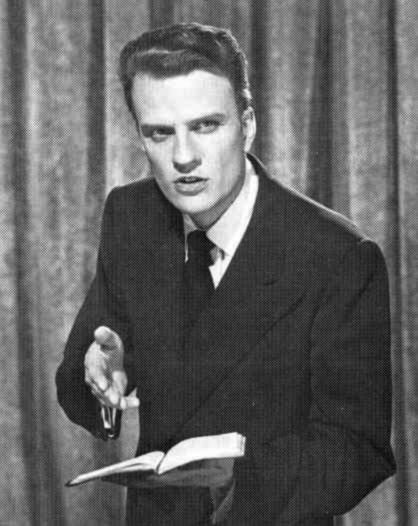

There were also the widely attended Christian revivals or “crusades” conducted by the young Billy Graham. In California in 1949, in an 8-week period, Graham drew a total of over 350 thousand people to hear him preach spiritual revival, the call to being born-again* in the Christian faith, and to live by such faith as America’s ancestors once had. From that point on Graham would cover the country from East to West with his crusades, building in popularity year after year (actually still quite strong in his ministry all the way up until his death in 2018 at age 99!)

There were also the widely attended Christian revivals or “crusades” conducted by the young Billy Graham. In California in 1949, in an 8-week period, Graham drew a total of over 350 thousand people to hear him preach spiritual revival, the call to being born-again* in the Christian faith, and to live by such faith as America’s ancestors once had. From that point on Graham would cover the country from East to West with his crusades, building in popularity year after year (actually still quite strong in his ministry all the way up until his death in 2018 at age 99!)

And it was Vereide and Graham working together that led Congress in 1952 to enact the National Day of Prayer, also held annually the first Thursday in May (although in recent years that event goes largely unnoticed by the press … and thus by the nation itself).

Yet that same American Christianity would evolve over the 1950s into something more of a civic religion than simply a deeply held spirituality. It blended easily into America’s self-image as a democratic or constitutional republic, supported economically by capitalism, all of them together, including Christianity, forming the foundations of that civic religion. Churches operated like well-managed corporations, sponsoring adult and youth clubs, social events, seminars on everything from marriage improvement to financial management, etc., all designed to fit everyone into Middle America, itself something of an object of reverence.

THE EISENHOWER ERA (1953-1960)

The Cold War now becomes a largely ideological battle. 1953 was a big year in terms of the changes that would occur in Cold War leadership. That was the year that Eisenhower took office as American president (January), and the year that Stalin suddenly, and most mysteriously, died (March). Those two factors would change the struggle from largely a military one to a largely ideological one.

The Cold War now becomes a largely ideological battle. 1953 was a big year in terms of the changes that would occur in Cold War leadership. That was the year that Eisenhower took office as American president (January), and the year that Stalin suddenly, and most mysteriously, died (March). Those two factors would change the struggle from largely a military one to a largely ideological one.

Eisenhower. Eisenhower was born in Kansas in 1890 to a rigorously religious family, and disappointed his pacifist mother greatly when he applied and was accepted for a free education at the U.S. Military Academy. He was then posted to Texas, where he developed excellent organizational skills. He was greatly disappointed when, just as he was about to be mobilized for war service, an armistice ended the Great War. He then continued in the postwar years in various officer roles, finally in 1935 being sent to the Philippines to serve as a Lieutenant Colonel under General MacArthur. Four years later he returned to the states as a staff officer to various generals, attaining the rank himself of brigadier general just prior to America’s entry into World War Two.

With that entry into the war, he was assigned to serve on the General Staff in Washington, where his strategic mind and cool head in the midst of personality clashes among top officers impressed greatly commanding general George Marshall. It speaks well of both men that when it was time to make the decision as to who was to lead the Allied armies on their assault on German-occupied France, a responsibility that by all rights belonged to Marshall, Marshall passed that opportunity for such historic honor on to Eisenhower … because Roosevelt pleaded with Marshall to remain in Washington as his much-needed military counselor. Marshall was well aware of how this would shape the larger careers of both men, bringing Eisenhower, not Marshall, to great public notice.

But the decision served the Allied forces very well because of Eisenhower’s ability to keep his cool head and strategic focus amidst the competition going on among Allied generals Montgomery, Patton and de Gaulle. He also worked easily with Soviet General Zhukov.

After the war, Eisenhower became Truman’s Army Chief of Staff when Marshall was sent off to China to try to get Chinese leaders Chiang and Mao to work together. With Marshall’s return, Eisenhower would keep that position, Marshall now becoming Truman’s Secretary of State.

1948 was a big year for Eisenhower, as both the Democrats and Republicans asked him to run as their presidential candidate, Eisenhower refusing both parties this great honor. But he did accept Columbia University’s strange request that year for him to serve as the university’s president, strange because Eisenhower and the professorial world were two very different universes.

Tensions would naturally result, even though Eisenhower proved to be more the scholar than anyone had expected, Eisenhower serving on the prestigious Council on Foreign Relations, as well as founding the American Assembly, an organization devoted to bringing together leaders from all areas of American life to go over a huge range of issues facing American society. This brought him into close contact with the business world, which the Columbia professors distrusted greatly at the time. But he would continue in that university position even when named NATO commander, in fact all the way up to his inauguration as U.S. president in 1953.

Actually, as president, his impact on the American Christian world was just as great, he being a regular churchgoer and a public advocate of the importance of America being a nation of Christian faith and prayer. He was thus a strong supporter of the presidential prayer breakfasts, and the Congressional decision to have the words “under God” added to the nation’s Pledge of Allegiance in 1954 and “In God We Trust” confirmed as the nation’s motto in 1956.

Eisenhower hosting the 1956 Presidential Prayer Breakfast

Thus at a time when Christianity seemed to be on a downward trend in Europe (seemingly even wiped out in Stalin’s Russia and East Europe) with much help from Eisenhower, Christianity stood out tremendously as forming the moral-spiritual underpinning of mighty America, that defender of the “Free World.”

To Eisenhower’s way of thinking, America had a mission, and it was quite clear what that was to be: to bring the world as close as possible to the ideals of Christian America itself.

McCarthy finally brought down. In 1954, Senator McCarthy succeeded in overplaying his hand, was silenced in the process, and then was finally censured by the Senate for his behavior.

McCarthy about to be brought down by the man he is attacking, lawyer Joseph Welch, who is representing the U.S. Army, accused of harboring “subversives” – June 1954

And at that point, America seemed to be ready to move on. The fear of Communism had not died, but had greatly subsided, no doubt in part because of Stalin’s death in 1953, and Russia’s willingness to present a new face to the world.

But sadly, the moral-spiritual wounds delivered by McCarthy to the world of Intellectual America would not heal. And Intellectual America would hold Middle America to blame for those wounds − Middle America’s “Puritanism” supposedly the basis for the McCarthyite phenomenon. Consequently, a spirit of vengeance, not healing, would simmer in the hearts of Intellectual America. But for the time being, Middle America held dominion in the land, so there was little that Intellectual America could do to find “justice.” But things would soon change in that regard, beginning in the mid-1960s.

Eisenhower’s “People to People” Program. In 1955, quite in line with Eisenhower’s understanding of America’s moral mission to the world, Eisenhower held a conference to explore the idea of simply sending Americans abroad – and similarly receiving people from abroad – as a way of building greater global understanding of the “American Way.” And indeed, in 1956 such a program was established within the U.S. Information Agency, to connect Americans and people overseas through sporting events, musical concerts, theatrical tours, “sister-cities” town twinning, various medical services, and even as pen pals. And bringing public notice to this program were such figures as the actor Bob Hope, Walt Disney, the Peanuts cartoonist Charles Shultz, and many others.

Eisenhower promoting his People to People program

His “People to People” program certainly impacted lives both at home in America and abroad. But other things, things based simply on the way power works in the larger realm, would overshadow greatly Eisenhower’s efforts to bring the world to a higher understanding of life.

Overseas developments

A workers’ uprising in East Germany (June 1953). Stalin’s death produced an immediate reaction in East Germany, where there was deep German discontent with Communist dictator Ulbricht’s collectivizing (government grab) of East Germany’s farmlands. With Stalin gone, it was easy for East Germans to presume that a new order was coming their way, and headed to the streets … particularly in Berlin (but also elsewhere). But an alarmed Soviet collective leadership responded in quite the Stalinist style, sending 20,000 Russian troops to join 8,000 East German police in suppressing the rebellion most violently. Yes, change in Soviet style was likely to occur, but not yet along the lines hoped for by many.

Further attempts at unity in Europe. Meanwhile, America’s European allies came up with the idea of forming a European Defense Community (EDC), one that would integrate a rearmed Germany into a European army under a fully international command. But the French found the idea too frightening and voted “no” to the idea in a national plebiscite held in 1954. Consequently, the decision was made (May 1955) simply to place the military of a newly independent West Germany into NATO as one of its units. But this inspired the Russians at the same time to set up their own multinational military, under the provisions of their Warsaw Pact. Thus those countries “behind the Iron Curtain” that were brought into that pact came to be known also as the “Warsaw Pact countries.”

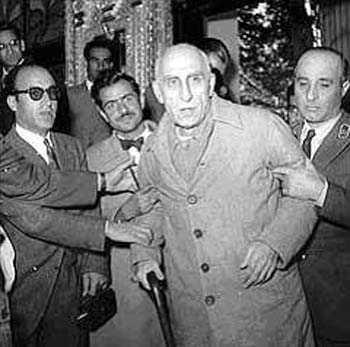

Iran (1953). In 1951, Iranian Prime Minister Mossadegh nationalized the huge holdings of the British oil industry in his country … the British finding that there was little they could do to reclaim their losses. And America was deeply absorbed in the Korean conflict. But with the Korean War over in 1953, Eisenhower took a stronger interest in Iranian developments − as Mossadegh tightened his power in the face of a growing Muslim militancy under the Ayatollah Kashani … and America’s young friend, the Shah, saw his own power diminish. But most disturbing of all was the growth of the Tudeh (Communist) Party as the main Muslim opponent. To Eisenhower’s way of thinking, Muslim resistance should come from pro-Westerners (actually rather numerous in Iran) rather than from the Communists.

Ultimately, with British and American support, the Shah called for Mossadegh to step down − the Shah clearly having the right to do so. But Mossadegh refused, called on his supporters to take to the streets in protest against the Shah’s “coup,” and forced the Shah’s new appointee, Zahedi, to go into hiding. At this point Iran became chaotic. And the Shah decided to head to Italy, to watch from a distance what was going to happen next!

So the American CIA tried a special trick: to pay Tudeh members to take to the streets that August, giving the appearance of the Communist Party supporting Mossadegh − as if Mossadegh was preparing Iran to be taken over by the Communists! Now pro-Shah supporters were joined by Kashani’s Muslim traditionalists, and also the Iranian military. Thus Mossadegh was arrested, pro-West Zahedi placed in power, and the Shah returned to Iran, in company with the American Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles. America and Iran were now close allies!

Mossadeq under arrest

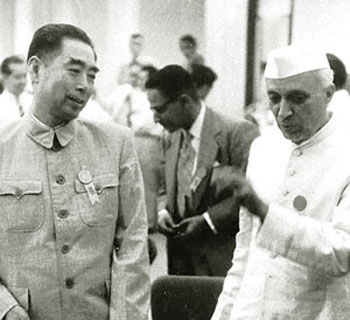

The “Third World” gets in the game (1955). An interesting side development was a gathering of representatives of numerous Asian and African states (constituting about half the world’s population) for a meeting at Bandung in Indonesia in 1955. Behind the idea of a unification of states desiring to remain neutral in this East-West confrontation were Indonesian dictator Sukarno, India’s leader Jawaharlal Nehru, and, interestingly enough, not so “neutral” Mao’s China. In remaining neutral, they would together constitute a “Third World.” Actually, since none of these countries had ever found themselves as colonies of Russia, but plenty of them had formerly been British, or French, or other European colonies, their “neutrality” had a certain “anti-European” or “anti-West” quality to it. Certainly the participation of Mao’s China added to that appearance.

China’s Chou En-lai (Zhou Enlai) with India’s Jawaharlal Nehru at Bandung – 1955

Actually all this seemed to have little impact on the larger world of international diplomacy. But it did give the world the term “Third World,” which most ironically came simply to be assigned to the numerous countries of Asia and Africa caught in a state of ongoing poverty and political violence. Some would even use it to refer to certain Latin American societies.

A supposed “thaw” in the Cold War (1956). Little by little, it became increasingly obvious that among the members of the post-Stalinist circle, Nikita Khrushchev clearly was the frontrunner. And then in 1956, with his speech denouncing the horrors of Stalinism and announcing his own quest for a “thaw” in East-West relations, it was clear that only a Russian supreme ruler could dare to issue such a speech.

What Khrushchev was declaring in his speech was that the East-West conflict was one of ideology, not military superiority. And Khrushchev was certain that the future belonged to the world of Communism, supposedly more focused on the welfare of the world’s lower social circles (such as the inhabitants of the “Third World”) than was capitalism.

And Eisenhower also saw matters in the same ideological way, from the American standpoint of course. Thus it was that America’s Radio Free Europe (RFE) broadcasting station busied itself constantly transmitting events and news eastward into the Soviet bloc, posing as a friend of the oppressed of East Europe, and ready to help the people behind the Iron Curtain free themselves from Communist oppression.

The Hungarian uprising and the Suez Crisis. October and November of 1956 would prove to be a major jolt to the world, because two major international events, with no other connection with each other except their timing, were to break out in that small window of time.

University students in Hungary were watching closely this East-West ideological contest … and – believing (thanks to America’s RFE encouragement) that they had American support – they decided that with a less militaristic Khrushchev in charge in Russia, they could break Hungary free from the Russian grip. Thus in late October, student protests flared in the streets, building quickly in Budapest and other Hungarians cities.

Hungarian rioters and dead security men

Meanwhile, tensions had been building in Egypt when in July of that year Egyptian President Nassar grabbed the Suez Canal, owned and run by the British and French. He needed funds to build his Aswan High Dam … designed to produce the energy needed to develop Egyptian industry (Egypt being one of the few Arab countries not sitting on top of very lucrative oil fields). As the weeks and months dragged on, negotiations had brought Britain and France no satisfaction. Thus − in alliance with Israel − at the end of October, all three countries, Britain, France and Israel, struck Egypt and regained the Suez Canal. It looked as if that had settled matters. Nasser had lost. Britain and France (and Israel?) had won. But to the Arab world − and much of the Third World − the results of the Suez Crisis was simply European imperialism at work.

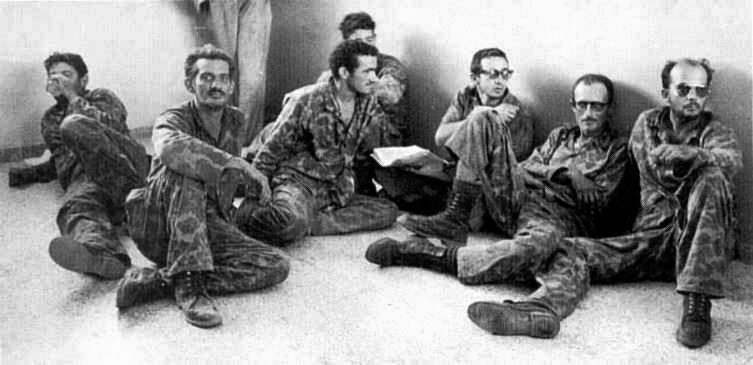

French troops with Arab prisoners

And seeing such British and French imperialism as a grand moral cover for what Khrushchev knew he had to do, in early November he sent thousands of tanks and hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops into Hungary to put down the student rebellion, killing some 2,500 Hungarians (but losing 700 Soviet troops) in the process. Thousands of Hungarians were arrested (20,000 – 30,000?), hundreds executed, and some 200,000 sent fleeing their country.

Ideologically speaking, this made Khrushchev look bad. But it also made him look strong. And the latter would have a much bigger impact on how much of the rest of the world reacted to this event.

As for the American reaction, whatever RFE promised those Hungarian students never actually materialized, making America appear to be very weak and indecisive. Worse, Eisenhower actually voted with Russia in a Security Council resolution (vetoed by Britain and France, of course) calling for Britain, France, and Israel to return the Canal to Nasser. Eisenhower was deeply angry with his British and French NATO allies because their actions at the Canal not only merely drove the Arab world more strongly into the pro-Soviet camp, America’s NATO commitment might have dragged America into a war that America had absolutely no interest in. And it made Russia appear to be no more an oppressor than Britain and France. Thus whatever ideological gain Eisenhower was hoping to get from the Hungarian Crisis he considered lost because of the Suez Crisis.

In the end, a deeply humiliated Britain and France (and Israel) submitted to such pressure. Britain would get over this shaming; France not so much, especially when it came under de Gaulle’s presidency (1958), de Gaulle already being hostile to all Anglo (British and American) interests.

And any hope faded away in East Europe that, with American support, Russia would finally have to lighten its grip over their countries. Even the pro-American leader of the new West Germany, Konrad Adenauer, would grow uneasy about the matter of exactly how much his people could depend on America and its NATO promise of protection if trouble should come West Germany’s way from the Soviet East.

And of course it all made Nasser now something of the great leader of the Arab world, able to humiliate not only Britain and France, but also rather more subtly America. And indeed, in 1958, Syria would unite with Nasser’s Egypt in forming the United Arab Republic, in the hopes of starting up a single, all-powerful Arab nation.

West Europeans unify even more deeply (1957-1958). In March of 1957, representatives of Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany gathered at Rome to sign a treaty designed to unite their economies even further by creating the European Economic Community (EEC). Upon the approval of the parliaments of these members states − which they all did quite quickly – the EEC then entered into effect at the beginning of 1958. In essence they had created a “Common Market,” opening their products to each other without tariffs or restrictions. At the same time, they created another organization, Euratom, to similarly unite their atomic energy programs.

European representatives designing the Treaty of Rome – 1957

America, of course, was very supportive of these developments, although it played no role in their actual creation or operation.

Britain chose not to join the effort, wanting to focus its economy on its Commonwealth partners (Canada, Australia, India, South Africa, etc.), and offer their farmers trade protection. However, in 1960, Britain and others would set up an alternative trade organization, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). But they had little economic interests in common, and the organization ultimately came to have little importance, especially as EFTA members came gradually to join the more effective EEC.

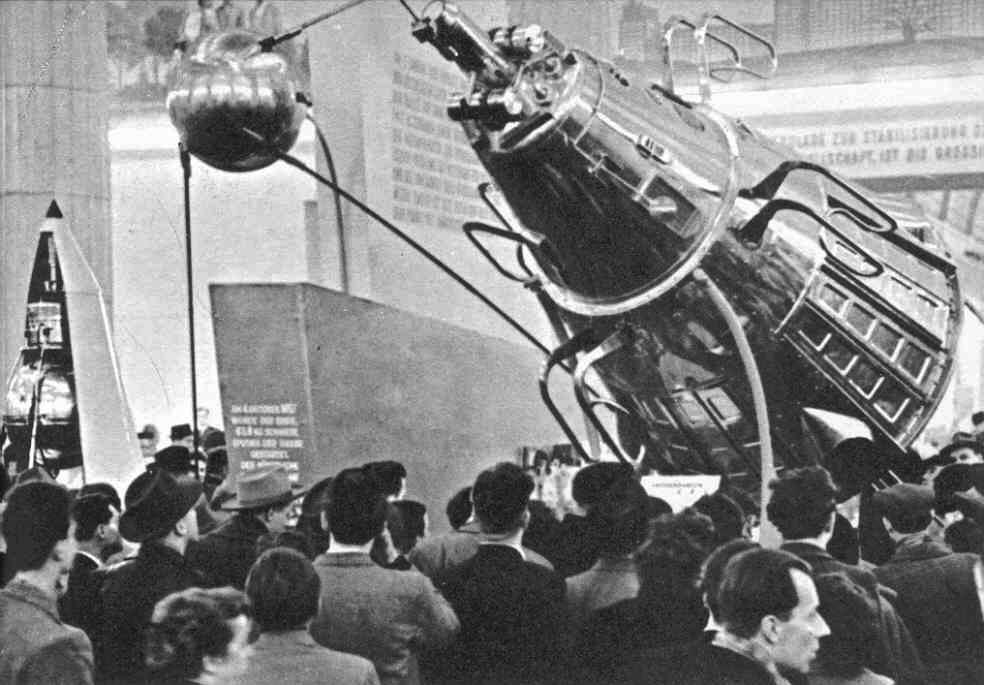

The Space Race. In October of 1957, Americans were awakened to the shocking news that the Russians had launched into orbit around the earth the world’s first man-made satellite. The Americans were shocked because nothing had been noted of such Russian technological development, as it was done in secret of course, with many unknown horrible disasters occurring in the process. American testing had always been done publicly and thus quite cautiously.

To Americans (and the world) this meant not only that America was “behind” in the technology race with Russia, the Russians now possessed a delivery system for nuclear weapons that had no means of being defended against. Then when the next month the Russians launched into orbit a rocket with a dog aboard, the shock was doubled.

Americans did not know whom to blame, but were feeling very let down by the technological world they had supposed was busy demonstrating America’s technological superiority. Ultimately, Eisenhower responded in 1958 by setting up the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to concentrate on developing aeronautical science, not aeronautical warfare, to put America back in the lead. This comforted Americans somewhat, but only somewhat.

Models on display in East Germany of Russia’s Sputnik (launched in 1957) and the more elaborate Sputnik III (launched in 1958)

Race relations in America

In this race to win the hearts and minds of the world in the midst of this Cold War, one huge blemish was quite evident in the American side of the picture, namely the horrible social position and treatment that Blacks had long experienced in their American homeland. The Soviet Russians were quick to point this out to a Third World that easily identified with Black America. True, there were Black notables receiving understandable respect from the White world, usually in the realm of sports and music, where Blacks certainly distinguished themselves. But beyond that, there was little recognition of the Black world by White America. Black America just didn’t even seem to exist.

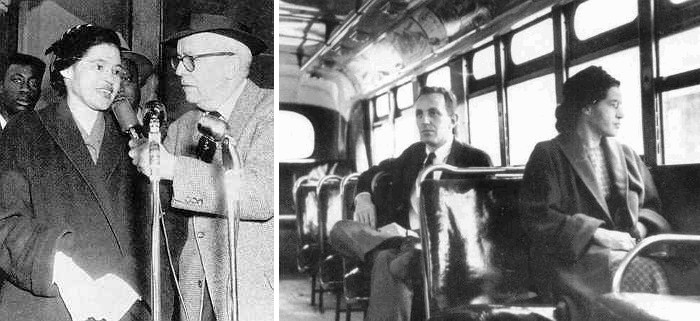

That was until a young woman, Rosa Parks, in Montgomery Alabama, in December of 1955, exhausted from a long day’s work, simply refused to move to the back of a bus to make seating available for Whites getting on the bus.

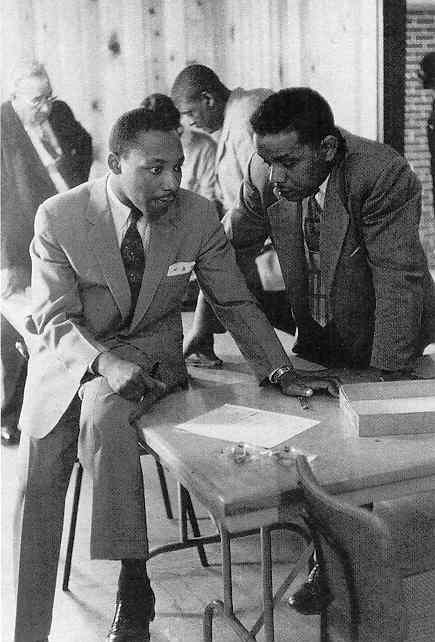

She was arrested for this “crime,” causing a young pastor of Montgomery, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to hit back by getting Blacks to refuse to use the city’s buses.

They would either have to walk to work or be picked up by their employers. This went on for a year, awakening the rest of the country, via the nation’s newspapers, to the tough situation facing Southern Blacks (not that they were doing all that well in Northern cities).

What finally decided the matter was a court case, Browder v. Gayle, brought before the U.S. Supreme Court, which declared Montgomery’s segregation laws unconstitutional.

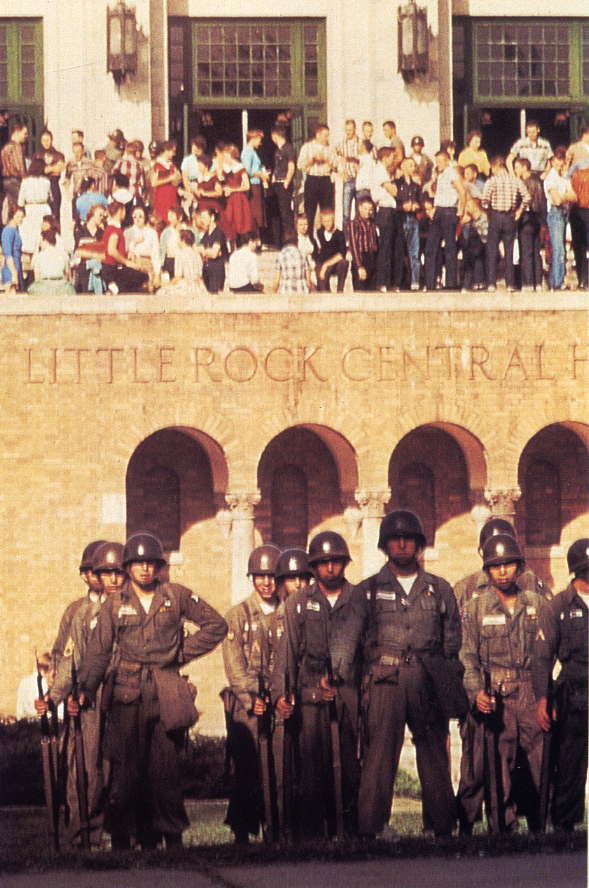

But Southern segregationists were not willing to give up long-standing Southern social standards. When the school board of Little Rock, Arkansas, decided in 1957 to admit Blacks to White schools, Arkansas Governor Orville Faubus, seeing strong support from White voters, called out the Arkansas National Guard to block the entrance of Blacks into Little Rock’s high school. But the city’s mayor called on President Eisenhower for help, Eisenhower then placing those same troops under his own command, also sending members of the 101st Airborne division to protect the few very brave Blacks making the effort to attend a White high school.

Members of the 101st airborne division in front of the Little Rock high school

Faubus struck back the next year (1958) by declaring the public schools now to be private schools, and thus beyond the reach of national authority, gaining public approval in a vote on the matter. But the Federal Courts again declared his actions illegal, and Faubus simply shut down the city’s high schools for the remainder of the 1958-1959 school year. But Little Rock was tiring of the drama, and the next year (1959) opened the schools to Blacks, with tensions running very high over the matter.

And that’s where race relations seemed to stand as America finished out the 1950s.

Eisenhower’s last years in office

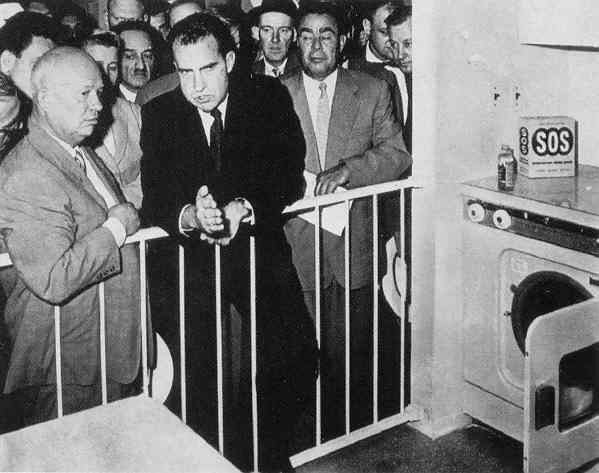

Nixon to Moscow (July 1959) / Khrushchev to America (Sep 1959). Eisenhower was deeply dedicated to the idea of finishing his two terms in office by bringing the Cold War to some kind of friendly ending. Thus in July of 1959, Vice President Nixon was sent off to Moscow to host America’s exhibition at Russia’s National Exhibition, where in front of a model American kitchen, Nixon held what became known as the “Kitchen Debate,” where he engaged Khrushchev in a friendly discussion about the differing lifestyles of the two countries.

Indeed, Khrushchev responded by coming to America two months later, to see firsthand the “American Way,” from farms to movie studios, Khrushchev enjoying his grand celebrity status that went with the visit. The supposition at this point was that “peaceful coexistence” had finally come to prevail in East-West relations. Thus plans were made to hold some kind of peace conference in Paris the next May (1960).

Khrushchev and his wife engaged in conversation with Hollywood stars Shirley Maclean and Frank Sinatra – 1959

The U-2 Incident (May 1st, 1960). Then two weeks before the scheduled conference, the world was awakened to the news that an American plane had been shot down over Russia. The Russians claimed that it was spying on Russia. But Eisenhower, believing that the crashing of a plane from those heights would have destroyed the plane and its pilot completely, claimed that it was simply a weather plane that had flown off course. But when the pilot proved to have survived (and was going to be held for trial) and huge sections of the plane survived as well, clarifying the fact that it was indeed a U-2 spy plane, Eisenhower found himself caught in his own lie, which Khrushchev went on long about Eisenhower’s dishonesty.

The question remained: why was the plane shot down when it was? These kinds of flights had been going on for some time. Why shoot one down now? Was Khrushchev being pressured from fellow Soviets to back away from the “peaceful coexistence” program?

In any case, the peace conference was called off. And Eisenhower lost not only public credibility but also his hope to see his presidency end on a very positive note. That was just not going to happen.

The Congo Crisis (June 1960, and after). In any case, there would soon be a number of events going on elsewhere that somehow would have shattered all that “peaceful coexistence” anyway. And one of those was the crisis that broke out in Africa, when in June of 1960 the Belgians turned their Congo province over to local leaders in the Congo’s move to “independence.” All hell broke loose as various leaders, and their tribal supporters, began to contest each other for control of the Congo, or move to split off sections of the Congo in order to set up their own separate “nations.”

Rather immediately, the U.N. Security Council agreed to send troops to try to settle things down. But these troops merely got themselves caught in the political contest going on there, America at first refusing to be part of the program, and then furious when the supposed Congo President Lumumba then turned to the Soviets for help. Seeing this as “the advance of Communism,” Eisenhower then decided to support another political contestant, Colonel Mobutu, who overthrew Lumumba, with Lumumba then being executed (January of 1961). This then also enabled Tshombe to take his mineral-rich Katanga province out of the Congo and operate as if Katanga was now a separate African nation.

U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold decided to involve himself personally in negotiating some kind of political reconciliation among the feuding parties. But his plane crashed in September (1961) while flying to Africa. And attacks began to mount against the U.N. troops (Irish and Italians), making the mess even greater. At this point, America chose to stay out of the whole Congo mess.

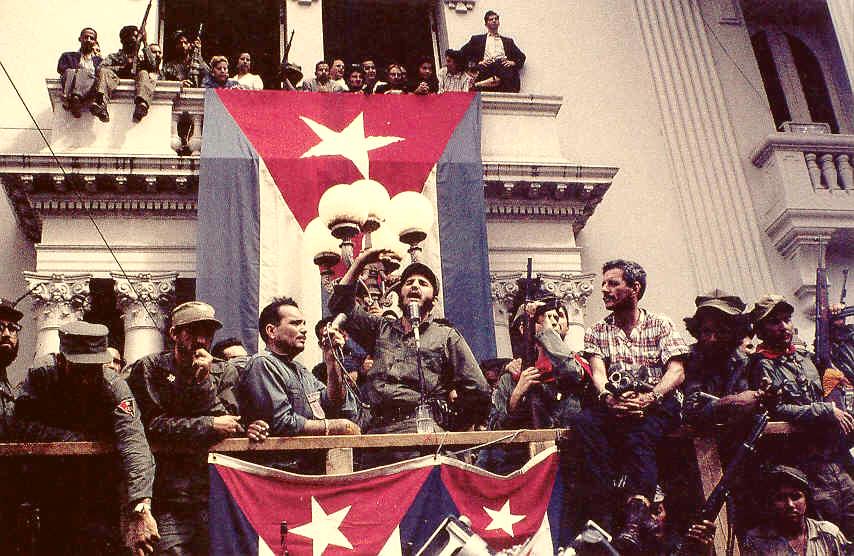

Castro’s Revolution. In part this was because a problem of a similar nature was developing right there offshore from Florida in nearby Cuba. Much to the delight of Americans, and with considerable help through Eisenhower’s 1958 effort to undercut the corrupt Batista regime with an American economic boycott of Cuba, in early 1959 the Batista dictatorship was finally overthrown in a Cuban “revolution.” This involved many different groups, but was seemingly led principally by the colorful Fidel Castro (the American press loved him).

Castro takes command of Cuba – January 1959

But it soon became apparent that Castro’s idea of “revolution” extended well beyond mere political change. In support of the peasant farmers of the country, he turned against members of the middle class, even ones that had played key roles in Batista’s overthrow.

When a wary Eisenhower did not lift the American boycott (Eisenhower was not greatly impressed by Castro’s political credentials), Castro then turned to Khrushchev for economic assistance. An alarmed Eisenhower then (mid-1960) responded by ending America’s purchase of Cuban sugar – its key industry. At the same time, American oil companies in Cuba refused to refine Russian oil shipped to Cuba. This infuriated Castro so much that he simply nationalized all American assets in his country (homes, banks, and sugar, coffee, and oil companies).

At this point (October) Eisenhower made the decision that Castro had to go, and got the CIA to start training anti-Castro Cubans at military camps in Guatemala and Honduras, in preparation for Castro’s overthrow. However, such action was scheduled to take place the following March, just after Eisenhower had left office.

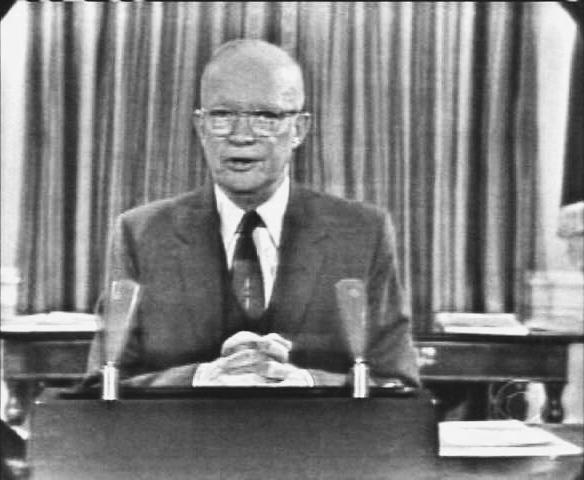

Eisenhower’s farewell address. Just before he was due to leave office (January 1961), Eisenhower addressed the nation via a television broadcast. In this he warned the nation about the dangers to American democracy posed by the growth of a huge military-industrial complex bent on taking over American political dynamics.

Having been military during most of his life, such criticism cut deep. But would the nation understand? In the eyes of the Vets, it was this same military-industrial complex that had helped win the world war. What did Eisenhower mean by this? They would eventually find out, although it was even more complex that just this single military-industrial grouping.

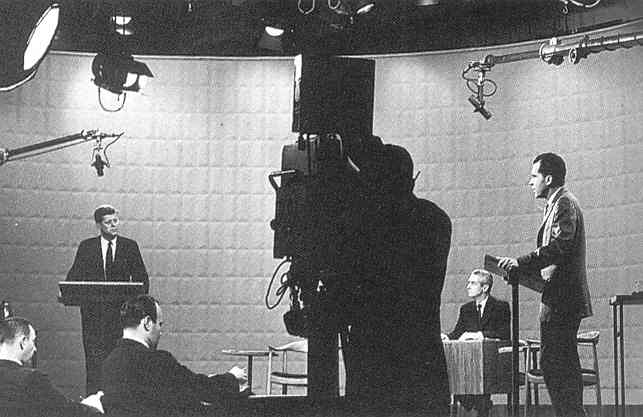

THE BRIEF KENNEDY ERA

The 1960 presidential election was closely fought between Eisenhower’s Vice President Richard Nixon and the oldest son of the politically aspiring Kennedy clan of Boston, John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Both men were seasoned national politicians, both deeply committed to national service, both excellent candidates. The major difference between the two was that the American Left had never seen reason to forgive Nixon for his earlier Congressional work in exposing treason within America’s leading political circles, and Kennedy was a much more attractive individual (and married to a quite attractive wife), as well as a Roman Catholic, the latter something of concern to basically Protestant Middle America. However, Kennedy assured America that he would not be representing the Vatican, but only the American people as president. Ultimately it was Kennedy that won the presidential office, but only by the narrowest margin of the popular vote.

The televised Nixon-Kennedy debates – 1960

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK). Kennedy came from a long line of Boston Democratic Party politicians, one grandfather a congressman and Boston mayor, the other a Boston businessman active in Democratic Party politics. His father, Joseph, was raised to privilege, did well in the 1920s stock market, got out just before the crash, and then did quite well in the whiskey import business with the end of Prohibition in the early 1930s. Joseph was very active in Roosevelt’s New Deal circle, heading up the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and then the Maritime Commission. Eventually (1938) Joseph was sent to London to be the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK). Kennedy came from a long line of Boston Democratic Party politicians, one grandfather a congressman and Boston mayor, the other a Boston businessman active in Democratic Party politics. His father, Joseph, was raised to privilege, did well in the 1920s stock market, got out just before the crash, and then did quite well in the whiskey import business with the end of Prohibition in the early 1930s. Joseph was very active in Roosevelt’s New Deal circle, heading up the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and then the Maritime Commission. Eventually (1938) Joseph was sent to London to be the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain.

John (or “Jack”) Kennedy was brought up, second oldest among seven siblings, in privileged circumstances (the prestigious Choate prep school and then Harvard), although his older brother Joseph, Jr., was being groomed by his father for the U.S. presidency from an early age.

John suffered serious back problems, but was able to work his way past them to get into the U.S. Naval Reserves just prior to America’s entry into World War Two. During the war he served in the Pacific, had his PT boat sunk by a Japanese destroyer, managed to save himself and a wounded crew member, was hospitalized, and had his tough times worsened by the news that his brother Joe Jr., had been killed in Europe.

Kennedy was a talented writer, had his Harvard senior thesis critical of the British failure in stopping Hitler in the early stages of the Hitler-problem published as a best-selling work, Why England Slept. Thus in the last days of the war he became a reporter, even called to cover the Potsdam Conference in 1945.

But with his brother Joe’s death, his family’s huge political expectations now fell on John, who in 1946 got the backing he needed to win (quite substantially) the congressional election that year, representing his home district. He was re-elected twice, before taking on the contest for the more prestigious senate race in 1952. That year he was able to defeat the experienced Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., and meet the woman that would become his wife, Jacqueline Bouvier, also a journalist, and sophisticated in a very French way. They would be married the next year, after she finished her coverage of Elizabeth’s coronation as British queen!

Kennedy would be hit again with back problems, but rise to the occasion by presenting a well-received speech at the 1956 Democratic National Convention, and then two years later by being easily re-elected to his senatorial seat. At this point he looked to the presidency as his next challenge

But in the 1960 race for the Democratic Party nomination, he was up against seasoned senate leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas. But Kennedy narrowly defeated Johnson in the first round of voting. Then, to the annoyance of his younger brother Bobby, who was his campaign manager, he asked Johnson to serve as his vice-presidential nominee. Johnson accepted the offer. This would turn out to be a matter of monumental importance to America, though hardly understood as such at the time.

As a Catholic, he was a visible attender at church mass, talked the Christian talk usually expected of a president, but kept his actual personal faith quite hidden from public view, as well as his extensive womanizing (which included even the movie star Marilyn Monroe!). But at the time, the latter was considered a topic not to be touched by the press.

Newly inaugurated Kennedy with Billy Graham, and Lyndon Johnson (among others) at the President’s Prayer Breakfast – February 1961

Kennedy’s “New Frontier.” In his inauguration speech he presented a new approach to America’s responsibilities to the larger world, a “New Frontier” for Americans to take on as a national challenge. He proposed to move America away from its supposedly more usual military approach, to something more like social and cultural service to the world, taking on the problems of poverty, disease, but also dictatorship, that crippled the world. He also issued what would become his famous challenge: “ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

And in this, the young president (youngest to take office, at 43 years old) found himself appealing to an even younger America, a generation who grew up during the war and thus a generation “in between” the post-war Boomers and the Boomers’ Vet parents. This generation was widely termed the “Silent Generation” because this generation still had something of the same patriotic instincts of the somewhat older Vets, and were indeed willing to quietly serve their country in response to Kennedy’s patriotic appeal.

They would fill the ranks of Kennedy’s Peace Corps, thousands of young American Silents sent out to the struggling Third World to show that world by their own personal involvement (two years’ service abroad) how to go about life in a better way, the American Way. Thus it was that the Peace Corps was hoped to be the centerpiece of Kennedy’s New Frontier.

Kennedy gretting Peace Corps volunteers – 1962

There were other aspects to this “newness” that appeared with the Kennedy presidency. One was to the capital city itself, Washington, D.C., which at the time had no more glamor than a typical state capital. Besides the Pentagon and numerous monuments, the city offered mostly just uninspiring bureaucratic office buildings, some residential areas in the city and surrounding areas, and a lot of poverty in neighborhoods inhabited by Blacks who came to D.C., but who had little to offer occupationally in what otherwise was strictly a clerical city. D.C. produced no other goods than documents!

But the Kennedys would begin the process of trying to bring some glamor to the city, if only through cultural events in the realm of theater, symphony, and art. But it was a start in the effort to make DC aspire to be something more like Europe’s capital cities.

Foreign relations under Kennedy (1961-1963)

The Bay of Pigs Fiasco (April 1961). But he was barely in office before he found himself having to deal with the anti-Castro militia trained during Eisenhower’s presidency and ready to invade Cuba that same April. This kind of muscling of an American neighbor was hardly what Kennedy wanted to present to the larger world as part of his New Frontier. But Kennedy felt that he could not call off the event, although he hesitated to offer the air support such a coastal invasion would require. He was hoping that somehow America’s hand in this attack on its neighbor Cuba would escape public notice, and yet that somehow this invasion would inspire Cubans to rise up and join the anti-Castro revolt. Otherwise, with no American air support, there was little likelihood that, as a purely military matter, this venture had any chance for success.

American-trained Cuban “liberators” captured by Castro’s military in the Bay of Pigs disaster

Ultimately the Cuban “Bay of Pigs” invasion was a grand disaster, America’s hand in the matter was clear to all (giving Khrushchev’s Russia all sorts of propaganda advantage), and Kennedy came across to the world as a very weak or indecisive leader.

The Berlin Wall (August 1961). Khrushchev thus saw in Kennedy’s weakness the opportunity to solve a problem his East German government was facing, namely the loss of a lot of professional talent and dedicated workers through the West Berlin escape route to the West. He would simply surround West Berlin with a mighty wall, and shut down all further access from East to West.

The Berlin Wall … a photo taken by me in 1962, less than a year after the wall went up

So the wall went up, with Westerners hoping that Kennedy might simply use his tanks to dare the East Germans to stop the American soldiers from taking those same walls down again. But ultimately Kennedy did nothing.

The Cuban Missile Crisis (October 1962). At this point, Khrushchev was becoming recklessly bold, figuring that he could make a complete mockery of American defense capabilities by placing nuclear-tipped rockets in Cuba, capable of reaching (and destroying) a good part of America.

It took a while for America to figure out what was going on in Cuba when sites for these missile bases were being cleared, Russia claiming that they were only for local defensive purposes. But when huge missiles started arriving in Cuba, it was clear what Khrushchev’s true intent was. These were offensive, not defensive, missiles.

Within Kennedy’s inner circle, debate went back and forth about what to do, not wanting to start a nuclear war by attacking those bases, but having to do something before they became fully operational. Finally, it was decided simply to place a naval blockade around Cuba, and then to dare Russia to try to bring more missiles through that blockade. But the question remained: who would blink first in this eye-to-eye confrontation.

In the end, it proved to be Khrushchev who blinked first, turning his ships back, and promising to dismantle the missile bases, minorly appeased by Kennedy’s promises to do the same to his American missile bases in Turkey (actually already under plans to be deactivated anyway!).

Clearly Khrushchev had gambled big, and lost. So it would be Khrushchev who would appear to be the weaker, even foolishly risky, personality – part of the reason that he was finally forced to step down from power in Moscow in 1964.

Vietnam. Kennedy was deeply concerned about Communism’s development in Southeast Asia. Laos, then Vietnam, seemed to be under the threat of going fully Communist. Kennedy had decided to remove the pro-Western Diem family from power in Vietnam – where the problems seemed to be developing rapidly – because Diem’s authoritarianism was presumed to be the reason democracy was not taking hold in South Vietnam. Diem was thus removed from power, in fact killed. But this happened just weeks before Kennedy himself was killed. So it is impossible to know what Kennedy had in mind as to what was to happen next in Vietnam.

President Diem, killed in the American “takedown” of Vietnamese authoritarianism – 1963

Go on to the next section:

America Divides