CHAPTER SEVEN

THE GREAT DEPRESSION … AND RISE OF THE DICTATORS

THE 1929 WALL STREET CRASH

American prosperity seemed, as the 1920s rolled along, to be an inevitable development, especially for those willing to put some personal money into the financial game that was behind this prosperity. Wall Street investors were doing great, inspiring American moms and pops to jump into the game themselves, some of them switching their life savings over to the investment program. And indeed as the 1920s were finishing out, it all seemed so wonderful.

“Market saturation.” But it was no more than a speculative game, based on what was supposed to be the profitability of the world of American industry. But what American industry was discovering over time was that most Americans now had their radios, washing machines, even cars (“market saturation”). Consequently, the market for those goods declined greatly, driving manufacturers to have to reduce their production levels and lower their prices to move their products at all, cutting back their profits greatly. And with that slowing production rate, they were also forced to let a number of their workers go. This was not pretty.

At first only the major Wall Street insiders understood what was going on, and began to sell off portions of their holdings. Others caught on and began doing the same, except now they were finding it more difficult to get others to purchase their holdings, and had to drop the prices of their offerings. Now others saw what was happening and tried to move in that same direction. And when this new Wall Street dynamic became widely understood across the American world, panic set in. In a mere matter of weeks at the end of October 1929, Wall Street crashed because of a panicked sellout of stocks for whatever prices (at this point very little) people could get for their holdings. Massive numbers of people now found themselves in financial ruin.*

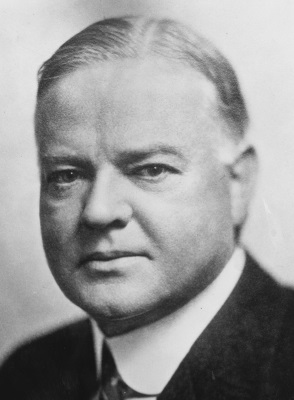

Hoover. This all happened during the first year in office of President Herbert Hoover. Hoover was very much the businessman, having previously built a huge business globally in the mining industry. But he was also very much the humanitarian, an orphan by the age 10, raised by an uncle, and therefore also very sensitive to the needs of the poor, in particular the laborers who worked for him.

When the Great War broke out in 1914, he stepped away from his business to help Americans trapped in Europe get home. He then used his business connections to help feed European civilians, principally the Belgians, whose lives were completely upset by the war. At the height of his effort, he was supervising the feeding of over ten million individuals per day, making sure the food got past the German troops to the hungry civilians.

And after the war he headed the American Relief Administration sending food to starving Germans, Russians and other East Europeans, no doubt keeping the number of Russians that starved during the Russian civil war at 6 million, rather than the 20 million that number would have been without his intervention. And then he helped his alma mater Stanford University gather research material about the causes of the recent war, resulting in the Hoover Library, and subsequently the Hoover Institution.

After the war, Hoover was appointed Harding’s secretary of commerce, a new governmental position that Hoover himself would have to shape. Basically, he saw his role as helping private industry take up more efficient and more modern business practices, in such areas as water management, electrical power generation, automobile safety, radio broadcasting, and a deep concern for the lives of sharecroppers, especially Black sharecroppers. In any case he saw his role to be one as an advisor, not governor, over any part of the economy from Washington!

Thus it was that now as U.S. president, even in the face of the horrible Depression, he saw his job as supporting the private sector, not replacing it with government economic programming. That may have been the view of the White House. But it proved not to be the view of the American citizenry, who looked in vain for someone, but especially the president, to fix the problem.

The “Bonus Army” and the 1932 elections. His standing with that citizenry would be merely worsened with the event that took place in Washington in the summer of 1932 when thousands of veterans from the recent war encamped themselves in the capital, resolved to stay there until they got some relief. They had served the country. Now it was time for the country to serve them. In particular, they had in mind the idea that a pension or “bonus” that had been promised to them for their service, but not due to come their way until 1941, should be paid to them now, but naturally at a reduced rate. They were desperate for something, anything, to break them out of the financial disaster they found themselves in. But Hoover balked at the idea of simply sending money to the protesters, and finally, when it was clear that the members of the “Bonus Army” were intending to stay until they got things going their way, Hoover sent in the military to clear them out, not a pretty sight. Americans were outraged.

Finally Hoover decided to put the U.S. government to work in developing a number of projects which would employ some of these people, the 1932 Emergency Relief and Construction Act. But it came too late in this vital election year to do much to boost Hoover’s standing with the American voters. And most ironically, opposition Democrats were quick to denounce this program as being nothing more than greatly detested “Socialism,” an attempt to turn Washington into a control center over the American economy. This was most ironic because that is exactly the program that Democrats would soon turn to when they won office in those November elections.

And they won it big, with their presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt winning office with a huge majority, and the Democrats doing the same in Congress. It was now a Democratic Party world.

ROOSEVELT’S “NEW DEAL”

Roosevelt. Roosevelt was born as an only child into a world of political and social privilege, raised according to certain aristocratic expectations by way of education at the prestigious Groton Academy under the Episcopal priest Endicott Peabody, then at Harvard. Peabody, indeed, would continue to be a major influence on his life. From Peabody he learned the importance of caring for the poor, a lesson in life that he would never forget. And when his uncle Teddy Roosevelt became president, he would have a role model and a sense of his own political destiny to follow.

Roosevelt. Roosevelt was born as an only child into a world of political and social privilege, raised according to certain aristocratic expectations by way of education at the prestigious Groton Academy under the Episcopal priest Endicott Peabody, then at Harvard. Peabody, indeed, would continue to be a major influence on his life. From Peabody he learned the importance of caring for the poor, a lesson in life that he would never forget. And when his uncle Teddy Roosevelt became president, he would have a role model and a sense of his own political destiny to follow.

He was also pushed hard by his aristocratically ambitious mother, Sara, and in part, to escape that controlling hand of his mother, he married a distant cousin, Eleanor (Teddy’s niece). Eleanor would have six children by him (though one would die shortly after birth), and find her world stressed by the ongoing presence of Sara, plus Franklin’s interest in her social secretary Lucy Mercer. Ultimately, Eleanor decided to stay married, but went on to develop her own social-political world, quite effectively as it turned out.

Roosevelt entered New York politics as a state senator, rose in importance in taking on corrupt Tammany Hall, and gained great notice inside the Democratic Party as a result (he chose to be a Democrat, rather than a Republican like his uncle Teddy). And in 1920 he was chosen to be the running mate to James Cox, the Democratic Party presidential candidate. But the Democrats did very poorly that year, and so Franklin did not gain that much-desired Vice-presidential seat.

Then the next year (1921) tragedy struck when he contracted polio, and was completely paralyzed from the waist down. But he did everything he could to develop his upper body strength − and continue his place in national politics. His strong support of the Democratic Party ultimately gained him that party support in his run for New York governor, a position he would hold (1929-1932) until he was nominated by the party as its presidential candidate in the race against Hoover … which Roosevelt won, and did so quite handily.

Now the country waited to see what it was that the new president would do to “solve” the problem of the Depression.

The New Deal. In his speech accepting the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination (July 1932), Roosevelt mentioned how he would undertake a “New Deal” to fix the American problem, although what that meant specifically was not clear, probably even to Roosevelt himself. But what was clear (made very clear in his March 1933 inauguration address) was that capitalism had failed, and the Federal government was going to have to take the lead in getting America back up and running again. Thus:

So first of all let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself, nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.

He was quick to blame “unscrupulous” capitalism for the disaster.

… rulers of the exchange of mankind’s goods have failed through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence, have admitted their failure, and have abdicated. Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men.

The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.

He also made it quite clear that the Federal government, especially the executive branch, was going to have to take the initiative in bringing the Depression to an end.

Our greatest primary task is to put people to work. This is no unsolvable problem if we face it wisely and courageously.

It can be accomplished in part by direct recruiting by the Government itself, treating the task as we would treat the emergency of a war, but at the same time, through this employment, accomplishing greatly needed projects to stimulate and reorganize the use of our natural resources. . . .

I shall ask the congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis − broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.

During his first “Hundred Days” in office, he set up a voluntary program by which merchants that agreed to hold their products to minimum costs would receive a Blue Eagle poster they could display at their shops indicating their compliance with the program. Pretty much all shops found themselves required to do so lest they got boycotted by the public.

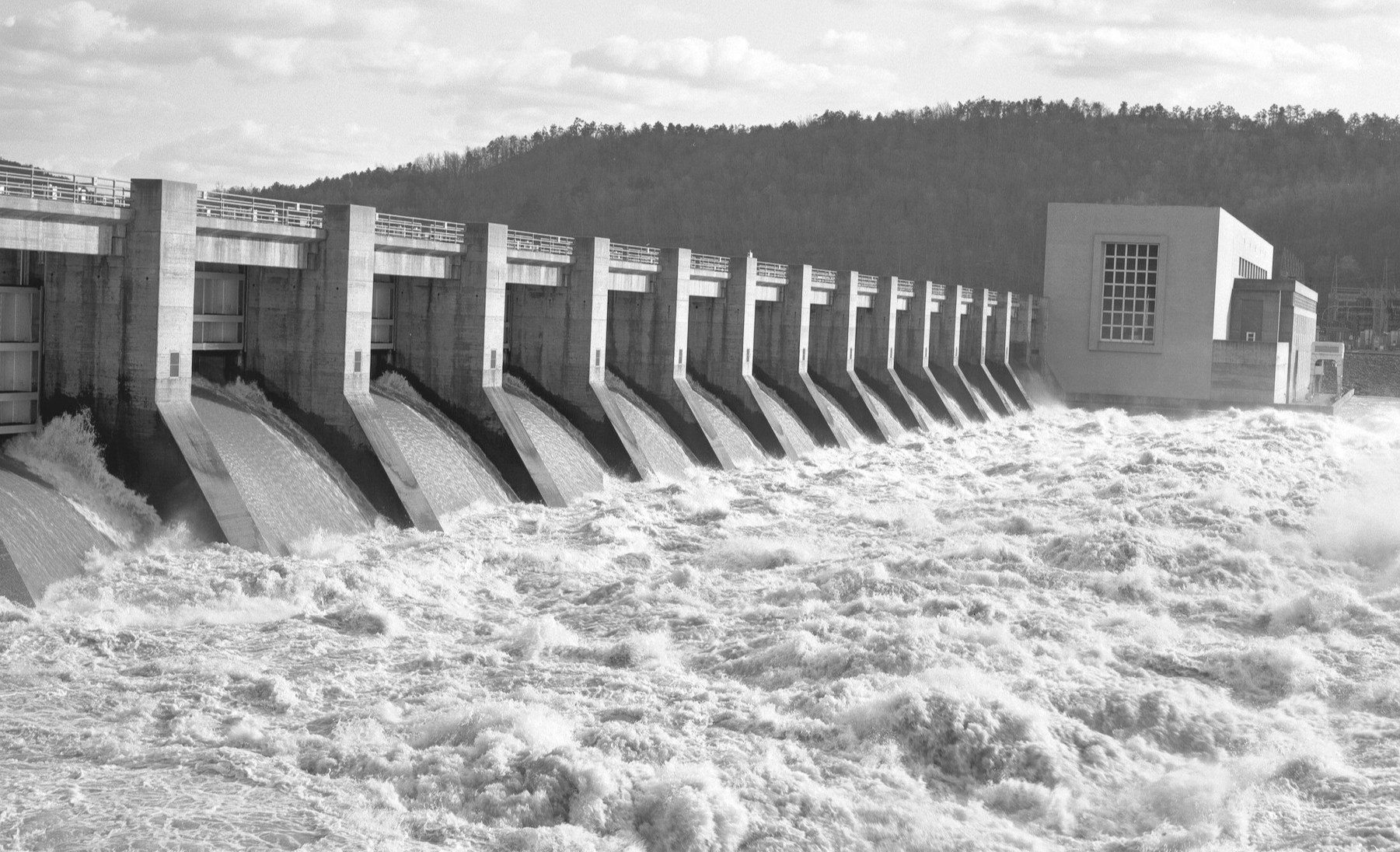

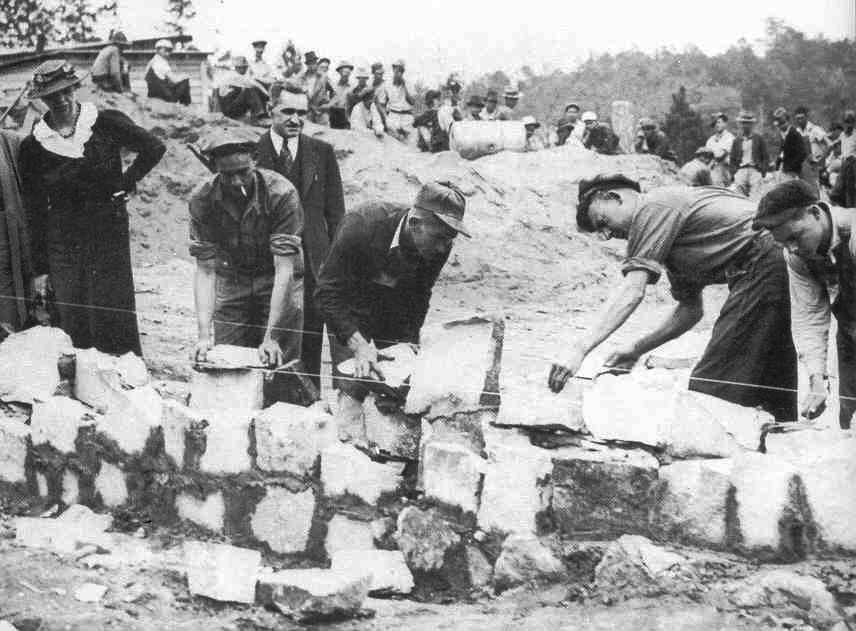

But he (and his “Brain Trust” of advisors) also moved quickly to undertake federally-directed public works projects designed to put the unemployed to work, most notably the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which employed three million individuals building 800 state parks and planting billions of trees. They put in place the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) to build dams on the Tennessee River, to control flooding and to bring electricity to the region.

And they undertook new regulations designed to lessen farm production (to keep farmer’s profits up), new government authorities such as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to insure depositors that they would be compensated for any bank failures (putting missing confidence back into the banking industry), and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to put the American stock market under some kind of regulation so as to prevent the wild speculation that had just destroyed it.

Roosevelt would go on to undertake even more Washington-directed measures to get America back in recovery, in 1935 setting up the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to insure home mortgages; in 1935 setting up the Social Security system to set aside portions of a person’s earnings and placing those in a trust fund that would one day offer them some pension funds in their days of retirement; and also in 1935, undertaking a massive building of American infrastructure (road, highways, rail services, dams, municipal buildings, etc.) under his Works Progress Administration (WPA).

New York City’s Triboro Bridge

Eleanor Roosevelt visiting a WPA site

These were all great additions to the American economy, the regulations that brought some discipline back to the world of American finance and the infrastructure projects that helped to continue the “modernization” of America, at a time that it had fallen into some kind of spiritual despair.

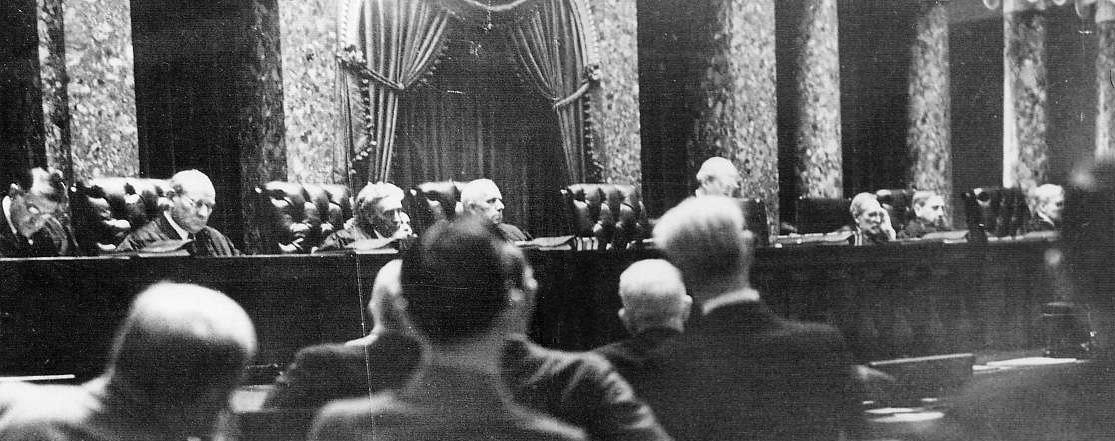

Supreme Court opposition. However, things did not roll out quite as easily as the description of these programs might make it appear. First of all, there was considerable opposition from the Supreme Court, which tried to knock down his programs (forcing him to reinvent his projects under new titles), claiming that he had no constitutional authority to undertake such federal economic initiatives.

So furious was Roosevelt with the court that in 1937 he tried to get Congress to support him in appointing additional members to the Court (“court-packing” it was termed at the time), but found the idea to be most unpopular, even with members of his own party, and backed away from the idea. Helping him in the matter, however, was the subsequent retirement of one of the judges, and the move in support of Roosevelt on the part of another. He thus could move on, supposedly.

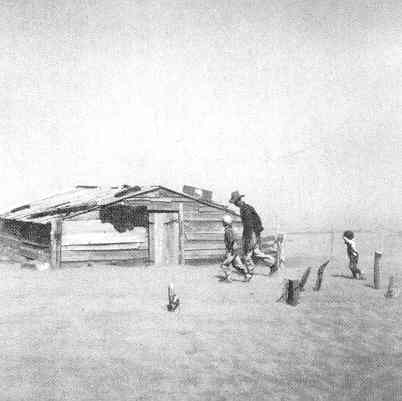

The “Dust Bowl.” There was also the ongoing drought in the mid-1930s that produced in the farmlands of the central states a “Dust Bowl,” destroying farms and forcing farming families to move west to find farm work, under the most miserable of conditions, conditions that never seemed to improve. There really was little that Roosevelt seemed to be able to do about the situation. And a discouraged America seemed to be losing its confidence in its president.

An Oklahoma dust storm – 1936

Private industry’s failure to revive. Then another problem developed, a huge problem, one that was destined not to be resolved, at least not the New Deal way. America had always been a society built on a spirit of personal entrepreneurship (from Puritans to cowboys, to farmers, to merchants, to manufacturers, etc.) and none of this, none of the New Deal, actually brought that spirit back to life. Depending on Washington to solve the country’s problems did not bring America back to action at its grass roots. Nor did it bring America’s all-important capitalism back to life.

The “market saturation” of government projects. Indeed, with the completion of all these New Deal projects, Washington experienced its own “market saturation.” It had built all the roads, constructed all the dams, developed all the parks and municipal buildings that it reasonably could think of, and thus Washington’s own market for government project dried up, just like private industry had done at the end of the 1920s. Thus with no more good ideas as to what Washington might do next, America slowly slid back into the depression. 1937 was not a good year, 1938 not much better, nor was 1939.

The coming war finally ends the Great Depression. What would ultimately bring America out of this economic stupor was not yet in view. But that was coming America’s way. With America’s entry in December of 1941 into a war that it did not want, it was forced to get itself back in business, producing war goods. And that it did, magnificently – restored capitalism employing millions of young Americans, those that did not find “employment” in the military itself! And that’s what finally brought America out of the Great Depression.

AMERICA’S DEPRESSION SPIRIT

By the second half of the 1930s, it was very hard for Americans to sit there and watch Hitler’s Nazi Germany show signs of growth, while America seemed to have no further ideas about how to move forward.

A migrant-worker mother and family in a tent – 1936

Unsurprisingly, many Americans began to develop feelings that America should be taking up some of the “Fascist” ways of the Nazis, the German state working closely with Germany’s industrial entrepreneurs (their “capitalists”) in getting things up and moving, especially along military lines.

Then on the other side of the political spectrum, Stalin’s Soviet Russia seemed to present a strong argument (especially to members of the American labor movement) that Stalin’s total state control of the economy would best serve everyone. Of course, Stalin had cleverly hid the huge price in lost human life involved in getting his Soviet state in such a commanding position in Russia. Indeed, it was foolhardy to go to Russia to see firsthand what was developing there, for those that saw too much never returned.

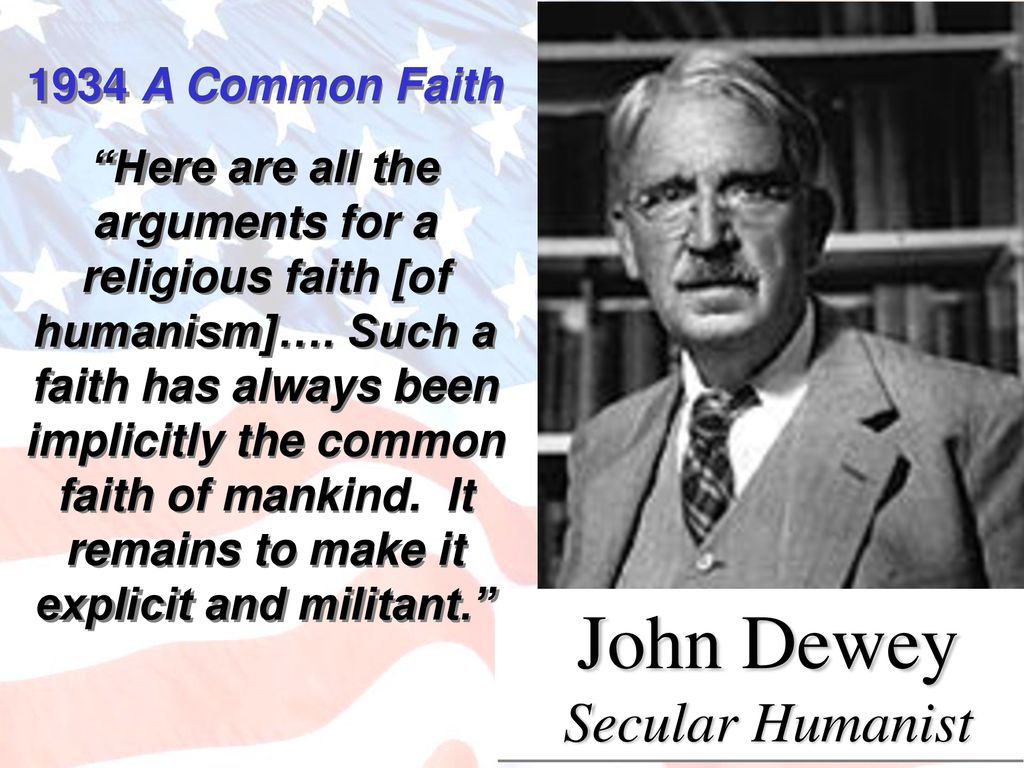

The 1933 Humanist Manifesto

To be sure, many Americans, besides simply Roosevelt’s New Deal organization, also busied themselves in trying to come up with solutions to the mess America found itself in. Intellectuals were particularly energetic in this endeavor. For instance, some 34 members of that intellectual world came together in 1933, just as the New Deal was getting off the ground, to come up with a broader view of the matter, not just suggesting some economic mechanics to deal with the Depression, but actually trying to invent a new worldview (actually not so new, really). As a result of their work, they published a Humanist Manifesto that same year.

The Humanist Manifesto was quite clear that it was trying to break America from the “non-productive” thought patterns of the past, ones in fact America had lived by pretty much since the country’s founding some three centuries earlier. To do this, they called for a new religion, one to replace America’s useless religious inheritance (Christianity), a new religion which they called “religious humanism.” Thus:

. . . any religion that can hope to be a synthesizing and dynamic force for today must be shaped for the needs of this age. To establish such a religion is a major necessity of the present.

The Humanist Manifesto then offered specifics in this matter with 15 theses or affirmations, some worth quoting here, for they speak very well of the mindset of intellectual Humanism, then and now.

FIRST: Religious humanists regard the universe as self-existing and not created. . . .

FIFTH: Humanism asserts that the nature of the universe depicted by modern science makes unacceptable any supernatural or cosmic guarantees of human values. Obviously humanism does not deny the possibility of realities as yet undiscovered, but it does insist that the way to determine the existence and value of any and all realities is by means of intelligent inquiry and by the assessment of their relations to human needs. Religion must formulate its hopes and plans in the light of the scientific spirit and method. . . .

SEVENTH: Religion consists of those actions, purposes, and experiences which are humanly significant. Nothing human is alien to the religious. It includes labor, art, science, philosophy, love, friendship, recreation–all that is in its degree expressive of intelligently satisfying human living. The distinction between the sacred and the secular can no longer be maintained. . . .

NINTH: In the place of the old attitudes involved in worship and prayer the humanist finds his religious emotions expressed in a heightened sense of personal life and in a cooperative effort to promote social well-being.

TENTH: It follows that there will be no uniquely religious emotions and attitudes of the kind hitherto associated with belief in the supernatural. . . .

THIRTEENTH: Religious humanism maintains that all associations and institutions exist for the fulfillment of human life. The intelligent evaluation, transformation, control, and direction of such associations and institutions with a view to the enhancement of human life is the purpose and program of humanism. Certainly religious institutions, their ritualistic forms, ecclesiastical methods, and communal activities must be reconstituted as rapidly as experience allows, in order to function effectively in the modern world.

FOURTEENTH: The humanists are firmly convinced that existing acquisitive and profit-motivated society has shown itself to be inadequate and that a radical change in methods, controls, and motives must be instituted. A socialized and cooperative economic order must be established to the end that the equitable distribution of the means of life be possible. The goal of humanism is a free and universal society in which people voluntarily and intelligently cooperate for the common good. Humanists demand a shared life in a shared world.

And it concludes:

So stand the theses of religious humanism. Though we consider the religious forms and ideas of our fathers no longer adequate, the quest for the good life is still the central task for mankind. Man is at last becoming aware that he alone is responsible for the realization of the world of his dreams, that he has within himself the power for its achievement. He must set intelligence and will to the task.

Signing this were Unitarian ministers, journalists, and a number of professors, including importantly professors of philosophy (Cornell, Columbia, Pittsburgh, Michigan) and even of theology (Harvard, Tufts, Chicago). We have already mentioned that Dewey was an inspirer of and signatory to this document.

It was very expressive of the kind of thinking that was common within comfortable and well-placed intellectual circles, then and now. To them, God is a terrible idea. Man should believe simply in man, Rational Man (such as they thought themselves to be, of course). This is what should lead human history.

But not surprisingly, but tragically, it put them in good company with rather authoritarian personalities found widely in ruling circles around the world, ones who frequently termed themselves as Socialists, though they liked to also use the term “democrats,” although “democracy from above” makes no sense. Democracy is conducted through the will of the people, not by those self-chosen to do their thinking for them, as was clearly the case of the “Democratic Socialism” that was supposedly taking place in Stalin’s Russia, and wherever else Marxism or Communism was running strongly

In the coming years, notably after the coming war, these same intellectuals would face the wrath of Cold War America, when it was discovered how closely their thinking paralleled Communist thinking. Of course these intellectuals did not intend for such an association. But it was there nonetheless.

And yet, despite their denials, they would still hold to these basic Humanist ideas, though in the early 1970s subtly present them in new ways in their Humanist Manifesto II (1973), most cleverly replacing the word “religious” with the word “scientific” in order to promote their Humanism now as “scientific Humanism.” Whatever the terminology, it still amounted to the same thing: to get America to see the world and its dynamics not in long-standing Christian ways, but in “more progressive” Humanist ways. In this, they would have the cooperation not only of the ACLU but also of the federal courts. More, much more, about this later.

Christianity struggles forward

Conservative and Liberal Christians go their separate ways. Where was God in all this? Christian Conservatives saw the times as one of a testing of their faiths, the challenge to go ever-deeper with God. Certainly that became the path that many of those hardest hit by the 1930s would take. Others would simply give up. And others would try to rescue the faith by attempting to make Christianity more “reasonable,” not a new thing, but one which the confusion of the times, and the times were indeed very confusing, certainly encouraged.

This produced enormous tensions within the “mainline” churches, ones that had long been the Protestant-Christian foundation of the country. For instance, Princeton Seminary’s J. Gresham Machen, left Princeton in 1933 because of its movement toward theological Liberalism, that is, by portraying Jesus as “saving” souls through proper moral guidance (the basis of the Social Gospel) more importantly than through the simple moral cleansing completed with his death on a Roman cross. Machen helped set up Westminster Seminary in nearby Philadelphia, where his more “orthodox” Presbyterianism would be taught.

This produced enormous tensions within the “mainline” churches, ones that had long been the Protestant-Christian foundation of the country. For instance, Princeton Seminary’s J. Gresham Machen, left Princeton in 1933 because of its movement toward theological Liberalism, that is, by portraying Jesus as “saving” souls through proper moral guidance (the basis of the Social Gospel) more importantly than through the simple moral cleansing completed with his death on a Roman cross. Machen helped set up Westminster Seminary in nearby Philadelphia, where his more “orthodox” Presbyterianism would be taught.

And this theological splitting would widen and deepen during the 1930s, with a rising number of new congregations birthed by more Pentecostal or conservative Christians leaving their denominations. But this merely left the older denominations more and more in the hands of the remaining Liberals. This did not however improve the role of those churches amidst this major spiritual crisis. Indeed the Liberal Christian message, the Social Gospel, proved to be quite unable to inspire those needing spiritual inspiration (especially when hopes for economic revival dimmed as the New Deal ran out of energy in the later 1930s).

As one of America’s greatest theologians, H. Richard Niebuhr, put things 1in 1937, in describing what had happened to the message of the American church:

A God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a cross. [Niebuhr, The Kingdom of God in America (1937)]

Fifield’s Spiritual Mobilization movement. But it seems that God was not finished with his call on America. An example of this is when Los Angeles Congregational pastor James W. Fifield found himself in the mid-1930s reaching out to other pastors, to get them to work with him in developing a strongly traditionalist movement, “Spiritual Mobilization.” This movement was dedicated to getting the message of America’s traditional Christianity preached widely from American pulpits. Fifield had a strong interest in seeing America’s “can-do” or entrepreneurial spirit back as the driving force in American life, not governmental direction and control. He was certain that this, not “enlightened Socialism,” was what God had always intended for America.

And this appeal was heard widely, and would, over the course of the latter half of the 1930s (and continuing into the 1940s and 1950s), bring thousands of American pastors into active support of Spiritual Mobilization.

Vereide’s prayer breakfast movement. Also out in the American West, another form of spiritual revivalism was on the rise. It started when Methodist minister Abraham Vereide left the huge Seattle Goodwill Industries that he had started up (employing thousands of handicapped workers) and found himself newly focused on meeting with distressed businessmen, distressed over the huge 1934 dockworkers strike that had shut down much of the West coast shipping industry. In San Francisco he gathered a number of local businessmen for breakfast and prayer, as a means of dealing with these distressing economic times, by going down a very different road than the one that Roosevelt’s New Deal had taken politically and financially. And when Vereide returned to Seattle (where the strike was also taking place) he did the same with a number of Seattle businessmen, then after that, meeting with them on a regular basis for breakfast and prayer. This would soon be joined by local politicians. And with this, the prayer-breakfast movement got strongly underway.

Vereide’s movement would spread across the nation, especially during the very challenging times of World War Two, becoming a regular part of the American religious scene. And from this would come in 1952 the first of the U.S. president’s annual prayer breakfasts, a continuing feature of Washington life since then.

The general strengthening of the American spirit. Certainly seeing the New Deal play itself out during the second half of the 1930s, and the Dust Bowl that hit the central U.S. about the same time, discouraged American hearts greatly. But despite these setbacks – even because of these setbacks – a strong spirit of resolve to take care of the immediate issues in front of them also hit American hearts.

Dust Bowl families heading West in the quest for work

This was not some kind of grand utopian spirit. This was instead a very strong determination to stay “real” in the face of the challenging natural world around them. And that “realism” took the form also of seeing that it was God himself who had placed these challenges in front of them, to see what their faith was actually capable of achieving, even if only in small ways.

Of course intellectuals did not tend to follow this kind of spiritual development, still caught up in their utopian faith in some grand mechanical program that was out there waiting for discovery. But Middle America was deeply reshaped by “reality,” namely that the “Roaring Twenties” were over, as well as the Rooseveltian New Deal dream. Consequently they were quite resolved to move ahead in the most pragmatic sort of way.

And it was very good, miraculous even, that this was the spirit that took hold of American hearts, because Americans would need just such a spirit to take up the challenges that would soon be coming their way in the form of yet another World War. God would be with them, and they would be very strong in understanding the importance of that divine support in fighting their grand cause. For Middle America, all of this would be a matter of fundamental reality, not utopian Idealism. They had a job to do. And by God’s grace, they would see that it got done. And thus America’s “Greatest Generation” began to take shape.*

THE RISE OF THE DICTATORS

Hitler’s Germany

Postwar Weimar Germany had actually been making substantial economic progress during the later 1920s, despite the huge reparations burden placed on it, meeting those obligations greatly by loans taken out with American banks. But with the onset of the financial crisis in America at the end of the 1920s, American banks called in those loans to save themselves, leaving Germany once again in trouble.

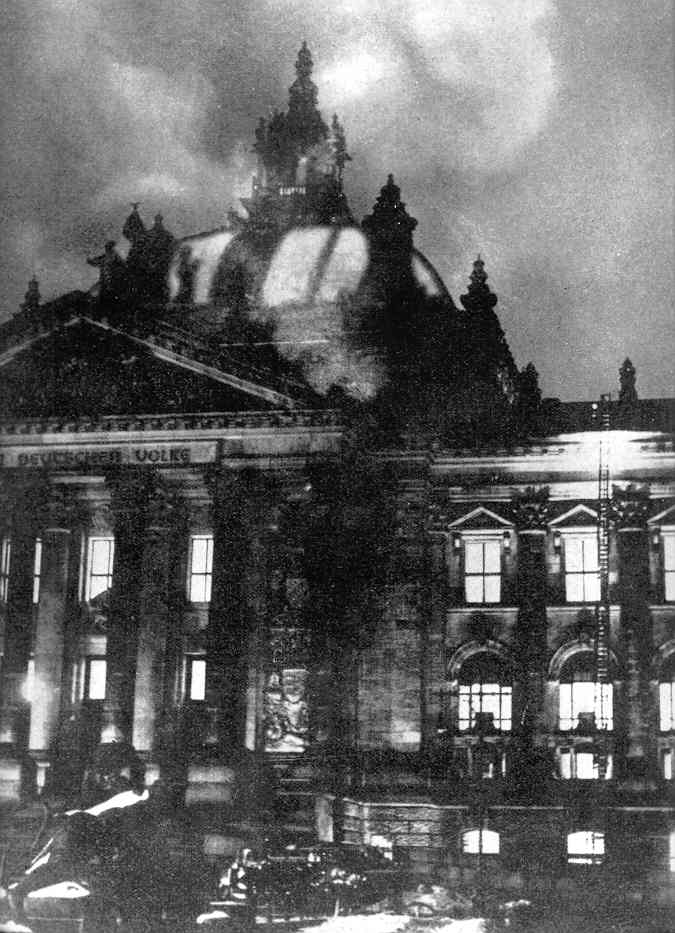

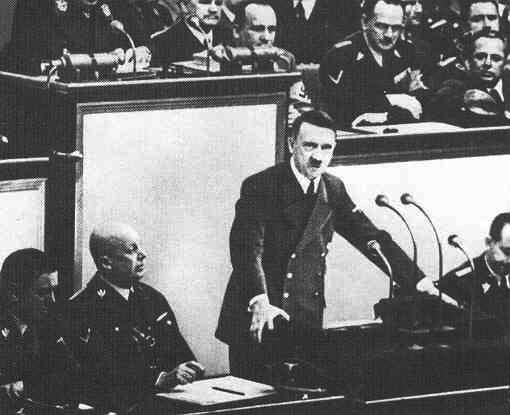

And this gave Hitler more political drama to play on, and make huge electoral gains for him and his Nazi party. By the end of 1932, his party was the largest in the legislature, with one-third of the seats. Hitler was then made Chancellor (Prime Minister) in January of 1933, as some kind of political compromise.

But his position was not secure, as parties of the Left were growing. But a fire in the parliament building (the Reichstag), just prior to the coming 1933 elections, allowed Hitler as chancellor to put the blame on the Communists, take emergency powers for himself, and have thousands of Communists arrested, giving his party (in coalition with a smaller Nationalist Party) the full parliamentary majority to govern Germany.

Then with the arrest of members of the other Leftist party, the Social Democrats, Hitler, as of the end of March 1933, found himself in total political control of Germany. In July, the Nazi Party was declared to be Germany’s only party. And when President Hindenburg died in August of the next year (1934), the offices of president and chancellor were simply consolidated into Hitler’s new position as Germany’s Führer (Leader).

Now began Hitler’s Neuordnung (New Order), politically, militarily, economically, socially, and even spiritually. Hitler drew the German multitudes in support of that program under the promise that this would make Germany truly a great power, the Germans as Übermenschen (superior people) even. And they seemed to love it, the vast majority anyway.

Now he targeted for “elimination” not only members of the political Left (Communist and Social Democrats) but also Jews, especially Jews. Hitler had a profound hatred of the Jews (even though he had a bit of Jewish ancestry himself), for they were not “Aryan” (and principally Germanic at that) in ethnic background, and had them removed from all positions of influence in German society, even those who had been heroic supporters of Germany in the Great War. And he had thousands (soon millions) carted off to work camps, to “serve” Germany in the most humiliating and life-threatening way. Actually, he wanted them removed entirely from German society.

Jews being marched off to work camps after Kristallnacht – 1938 (a night of destroying Jewish synagogues and businesses)

Most amazingly, Hitler was able to get German pastors in line with his “Aryan” thinking, causing them to come together in 1933 as the Protestant Reich Church. They would now be “German Christians,” giving Hitler full recognition as lord and protector of the German Church.

Not all pastors fell in line with this, but, as a newly reconstituted “Confessing Church” (1934), chose to move very carefully to keep themselves and their flocks under the lordship of Jesus Christ and him alone … the precise purpose of their new Barmen Declaration.

And Hitler began to amplify Germany’s rearmament (actually commenced even before he came to power), with the intent, made very clear in his speeches, of undertaking Lebensraum (Living room, that is, more territory for German settlement).

And he made it most clear that such Lebensraum was to be directed to the neighboring Untermenschen (inferior people) living to the East in the land of the Slavs: Czechoslovakia, Poland, the Ukraine, Russia, etc.

How others respond

Italy. Mussolini was very supportive of all of this, Hitler and Mussolini even in 1936 having signed a protocol announcing a political “axis” linking Berlin and Rome, around which all of Europe would eventually revolve. Thus these two countries would get the designation as “Axis” Powers.”

Mussolini had already, in 1935, made his own move in Africa to prove to the world that Italy was indeed a major European military power, when he had 300,000 Italian troops invade independent Ethiopia from Italy’s colony next door in Somaliland.

The Ethiopians did the best they could, appealing to the new League of Nations to do something about this undeserved Italian aggression. At the same time, Ethiopians conducted continuing guerrilla operations against their Italian occupiers.

But Britain and France did nothing, choosing not to read the rather clear political signs building in Europe. Instead they foolishly hoped at that point to enlist Mussolini as an ally in opposing Hitler’s obvious expansionist intentions in Europe. Finally, the League took action in calling for sanctions against Italy, which got largely ignored. American businessmen even continued to ship their American oil to Italy!

And as for the Italians, all of this international opposition simply rallied Italians more strongly around their Duce Mussolini!

Spain. Back in 1923, Spanish General Primo de Rivera performed an act similar to Mussolini’s in Italy, in simply grabbing power in order to settle down a chaotic Spain, chaotic because the society could not decide whether it wanted to hang on to the traditional image of its own glorious past or move into a modern industrial world, with all of the deep social changes involved in the process. But Rivera’s choosing to hang onto tradition never resolved anything, and in 1931 both Rivera and Spanish King Alfonso together decided to let the Spanish people themselves decide how they wanted to go forward, holding a national referendum on that matter that year. The election went in favor of modernization under a new Republic, and thus Rivera stepped down and the king abdicated.

But this would prove to be another case where democracy did not decide the matter, but merely served to make the Spanish civil strife worse, much, much worse. By 1936 Spain was caught in bitter civil war, which in turn decided General Francisco Franco to leave his position in Spanish Morocco and come to Spain to take up the traditionalist cause of the Nationalists or “Falangists” against the pro-modernization Republicans. This only made the civil war all the bloodier.

But this would prove to be another case where democracy did not decide the matter, but merely served to make the Spanish civil strife worse, much, much worse. By 1936 Spain was caught in bitter civil war, which in turn decided General Francisco Franco to leave his position in Spanish Morocco and come to Spain to take up the traditionalist cause of the Nationalists or “Falangists” against the pro-modernization Republicans. This only made the civil war all the bloodier.

But making the situation even more horrible was the reaction of the other European powers. Stalin’s Russia sent support to the Republicans, giving that group, deserving or not, the appearance of being strongly pro-Communist. Hitler and Mussolini were glad to support Franco, and to have the opportunity to try out some of their military talents in Spain, for instance bombing, killing and destroying the Basque city of Guernica. England and France also sent support to Republican Spain, though it was very timid in comparison, something of an indicator of the state of French and British diplomacy at that point.

Guernica … as a result of Italian “target practice” – 1937

America stayed out, though a number of Americans personally did not, going to Spain to volunteer their services, to one side or the other. American Catholics supported Franco, and American Liberals, such as the writer Hemingway, supported the Republicans, Hemingway eventually writing about that experience as a best-selling novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940).

Ultimately (1939) Franco brought Spain under his control, and would continue to hold Spain in that position all the way up to his death in 1975! But at the time, he and Spain were exhausted, and consequently Franco would work hard to keep Spain out of the military conflict that was clearly about to unfold in Europe – that same year (1939) in fact.

Go on to the next section:

World War (Round Two) … and Resulting Cold War