CHAPTER SIX

THE “GREAT WAR” (WORLD WAR ONE) … AND ANOTHER RECOVERY

AMERICA’S POLITICS AS IT ENTERS THE 20TH CENTURY

Politically speaking, America in the first years of the 20th century would find itself led by a number of presidential pragmatists, not necessarily of the philosophical variety, but certainly exemplary expressions of their progressivist times.

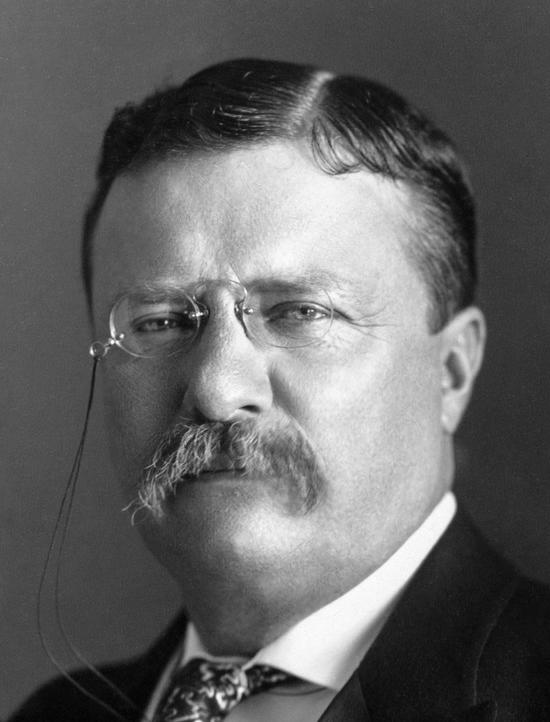

Teddy Roosevelt (U.S. president 1901-1909). Roosevelt was an amazing mix of political wisdom and monumental personal energy that would serve the country beautifully, especially in the breakup of the monopolies dominating the American economy. He was a strong reformer at heart. He grew up home-schooled and Europe-traveled, learning how to compensate for his vicious case of asthma by way of intense exercise. He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard (1880). And he then published an outstanding history of the War of 1812 (1882), entering New York politics that year as a member of the New York State Assembly.

Teddy Roosevelt (U.S. president 1901-1909). Roosevelt was an amazing mix of political wisdom and monumental personal energy that would serve the country beautifully, especially in the breakup of the monopolies dominating the American economy. He was a strong reformer at heart. He grew up home-schooled and Europe-traveled, learning how to compensate for his vicious case of asthma by way of intense exercise. He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard (1880). And he then published an outstanding history of the War of 1812 (1882), entering New York politics that year as a member of the New York State Assembly.

But tragedy followed his younger life, losing (1878) during his Harvard years the father he had traveled with so much. Then two years into his marriage, his wife died (February 1884) soon after the delivery of a baby … only ten hours later than when his mother died in the same house (he would, however, remarry two years later and have five more children!).

This drove him to work harder as a reformist, drawing him ever-greater notice. His effort to become a cattle rancher in the Dakotas failed in the face of the horrible winter of 1886-1887, forcing him to return to New York. And an attempt to run as New York City mayor also proved unsuccessful … though his popular book The Winning of the West (1889) got the attention of President Harrison – who appointed him to serve on the Civil Service Commission in D.C. Eventually he took up the position as a New York City Police Commissioner – ultimately its head – in which he took on the corruption rampant within New York’s Tammany Hall and its Boss Platt … to which Platt responded finally by having the Board of Commissioners eliminated.

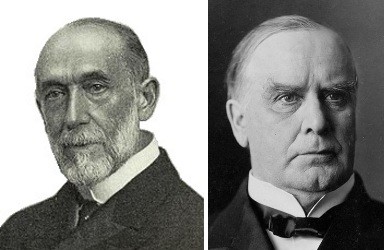

Platt McKinley

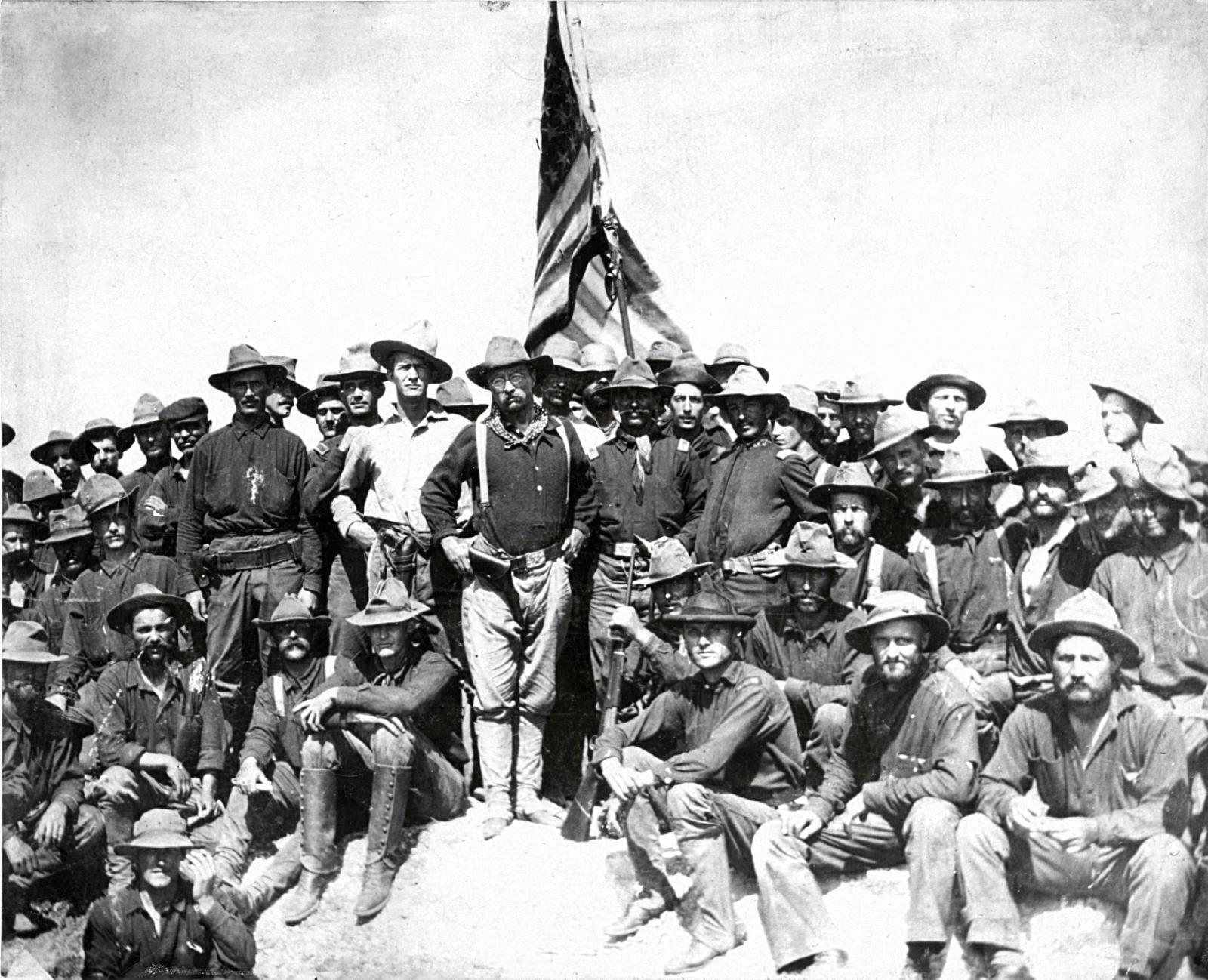

However, his support of William McKinley’s presidential run (1896) got him the appointment as Assistant Secretary of the Navy (1897), where, because Navy Secretary John Davis Long was a very sick man, Roosevelt proved himself to be a very excellent naval advisor to the president, very important at a time when America found itself now at war with Spain. But Roosevelt soon resigned, organized his own unit of military volunteers, the “Rough Riders,” and led them against Spanish defenders in the Battle of San Juan Hill (1898). This would make Roosevelt a national hero.

Roosevelt (center) and his Rough Riders – 1898

Then that same year he ran and won (narrowly) the position of New York governor, thanks to some kind of “understanding” with Platt. He would also come to understand quite well the art of political leadership amidst a deeply divided electorate. And he would use such wisdom to try to do the “right thing,” and thus he kept himself in touch (daily press conferences) with his Middle American supporters.

Finally, eager to get Roosevelt out of New York politics, Platt worked hard to get Roosevelt a position on the 1900 presidential ticket as vice president, running alongside McKinley. Roosevelt was well aware of how insignificant that position can be. But he found that he enjoyed campaigning tremendously. But yes, he quickly found the vice-presidential office to be very, very boring.

However, he would find himself in that position only briefly, when an insane anarchist shot President McKinley (September 1901), and Roosevelt consequently became the new U.S. president.

As president, Roosevelt was a very active anti-corruption activist, who did the country a great favor in enforcing the country’s anti-trust laws against the industrialists amassing huge fortunes. Using the 1890 Sherman Anti-Trust Act (originally intended merely to break up rapidly organizing American labor), Roosevelt not only broke up a number of huge trusts, he also stood strongly behind the 1907 Tillman Act outlawing corporate contributions to federal political campaigns, a much-needed effort to block big-money from directing the American electoral process.*

Roosevelt abroad. Roosevelt was also just as active abroad, doing what he could to impress the larger world with America’s new power. Thus he supported Panamanian “independence” from Colombia in 1903, after Colombia refused to let America continue to follow up on France’s failed effort at building a canal in the region connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. This then allowed Roosevelt to start up, under Panamanian agreement, the American owned and run Panama Canal Project (not completed until 1914). He hosted the Portsmouth (New Hampshire) peace talks in 1905 between Russia and Japan over their war in East Asia. He was a participant in the Algeciras (Spain) talks over Morocco’s future in 1906, throwing American support to the British and French and thus helping to back Germany away from its goal of taking control of Morocco. And to finish off his presidency, in December 1907 he sent off a fleet of 16 freshly painted (white) American battleships (the “Great White Fleet”) around the world, to let the world know that America had arrived as a great naval power.

Roosevelt sending off his “Great White Fleet”

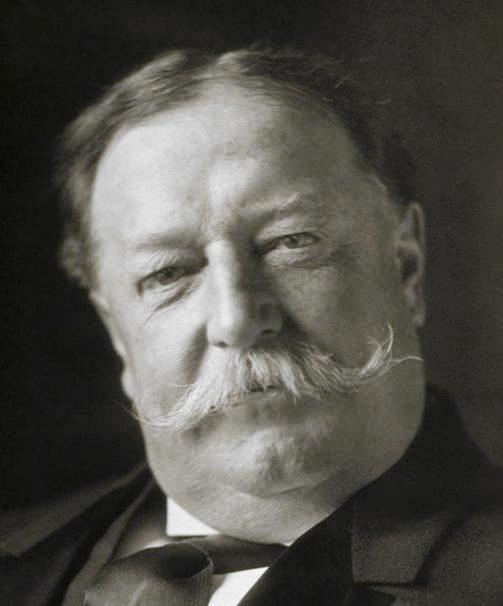

William Howard Taft (U.S. president 1909-1913). With Roosevelt stepping aside in 1908, he looked to his close friend Taft to take his place, and continue the policies he had put in place, especially the trust-busting. Taft was definitely a man of the law, appointed in 1887 as an Ohio judge at age 29 and then two years later being appointed by President Harrison as U.S. solicitor general. There in Washington, D.C. he would become close friends with Roosevelt, Roosevelt serving at the time on the Civil Service Commission. Two years after that, Harrison appointed Taft to the Sixth Circuit court, what Taft hoped was a stepping stone to a Supreme Court appointment.

William Howard Taft (U.S. president 1909-1913). With Roosevelt stepping aside in 1908, he looked to his close friend Taft to take his place, and continue the policies he had put in place, especially the trust-busting. Taft was definitely a man of the law, appointed in 1887 as an Ohio judge at age 29 and then two years later being appointed by President Harrison as U.S. solicitor general. There in Washington, D.C. he would become close friends with Roosevelt, Roosevelt serving at the time on the Civil Service Commission. Two years after that, Harrison appointed Taft to the Sixth Circuit court, what Taft hoped was a stepping stone to a Supreme Court appointment.

However, in 1900 he was appointed by President McKinley to head up a commission with the responsibility of organizing a new government for the Philippines, with an understanding from McKinley that this would lead soon to that Supreme Court appointment. But when McKinley was then shot (1901) that ended the deal.

But Taft’s responsibility for the Philippines would come to have great importance to Taft, who, when Roosevelt (now president) offered him an appointment to the Supreme Court, Taft turned him down, because he felt his well-publicized work on the Philippines project was not finished. So Roosevelt instead offered him the position as secretary of war (Taft’s father had held that position), which Taft accepted, because the war department was the American agency governing the Philippines at that time.

From that point on, Taft would actually serve as a personal assistant to Roosevelt, often delivering speeches and meeting with other officials on behalf of the president. The relationship was so close that two more times, when a Supreme Court appointment was offered to Taft, he declined.

Then when 1908 came around and Roosevelt decided to step away from the presidency, he pushed a reluctant Taft to run for the position, against the Democratic Party’s William Jennings Bryan’s third run for that office. Taft would win the race.

Now as president, Taft became even busier than Roosevelt had been in taking on the big-money capitalists, taking on 70 antitrust cases in his four years in office, compared to Roosevelt’s 40 cases in nearly 8 years in office. This would include the 1911 breakup of Rockefeller’s Standard Oil into numerous competing companies (although Rockefeller would continue to be a major stockholder in these new companies!)

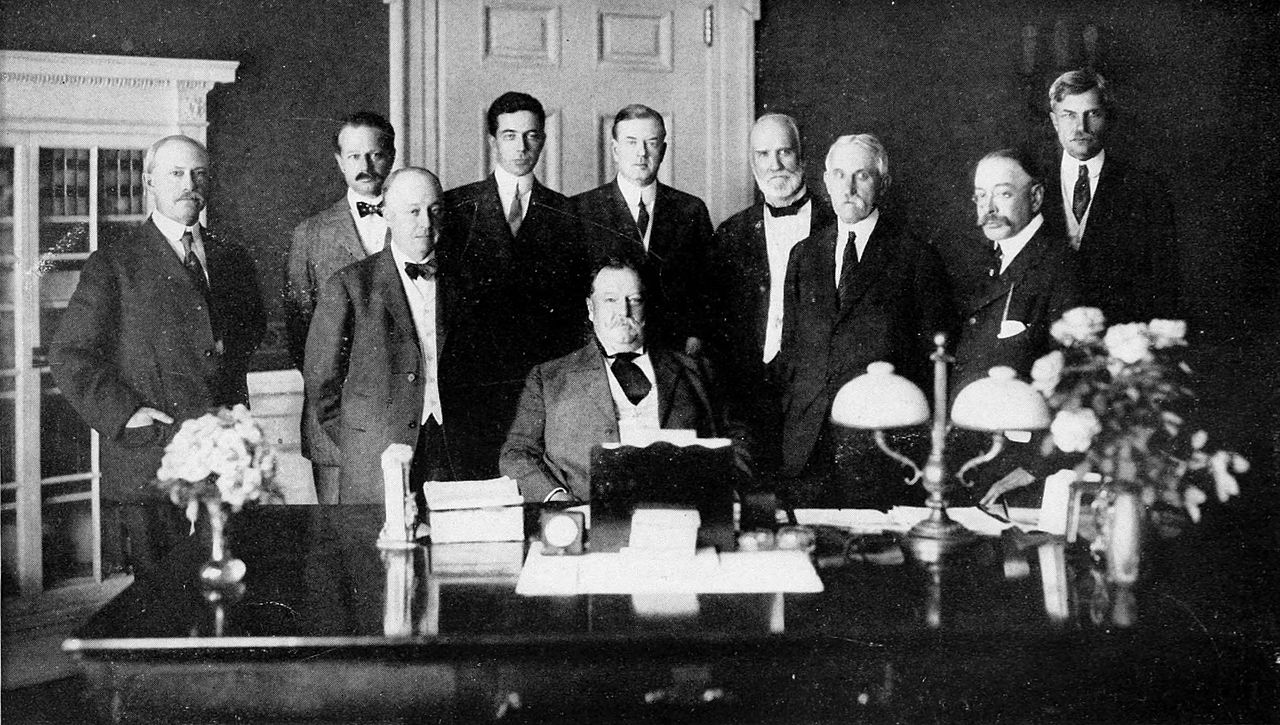

Taft and his cabinet officials – 1910

It is very important to emphasize this trust-busting feature of both the Roosevelt and Taft presidencies, because what they did helped to put in place key rules and restrictions (just like in sporting events) designed to keep the competitive dynamics that drives the capitalist system fair. Even Adam Smith, in his 1776 book Wealth of Nations, in which he first laid out very carefully the huge economic and social benefits of capitalism, was very clear on the dangers of the accumulation through this same process of society’s wealth in ever-smaller hands (monopoly). He well understood how this would impoverish the rest of society, and in the end actually destroy the dynamic capitalist economic system itself.

Sadly, American society seems to have lost such wisdom in recent years, letting happen exactly what Smith, in the name of capitalism, was highly opposed to, and what Roosevelt and Taft moved to keep from taking over the American economic system. We shall have more to say on this matter further on.

The 1912 election. Tragically for both Roosevelt and his friend Taft, Roosevelt was regretting deeply his earlier decision to step out of American politics … just as Taft decided to run for his second term in office in 1912. Roosevelt thus decided to reenter the race that year, producing an ugly political contest between the former friends. Ultimately all this achieved was to split the Republican Party, and bring to the presidential office the Democratic Party candidate, Woodrow Wilson, who otherwise had no serious chance of winning the 1912 election. Sadly, Roosevelt and Taft would never get past their mutual hostility over this event.

Roosevelt campaigning at the head of his own “Bull Moose” party – 1912

Taft would go on to teach law at Yale, until his friend, Ohio governor William Harding, won the presidency in 1920 and would then appoint Taft to the Supreme Court as its chief justice. Taft gladly accepted the offer and would serve in that capacity until his death in 1930.

Wilson. At this point (1913) America had as its president a former professor and Princeton University president (1902-1910), who had also just served briefly (1911-1913) as a New Jersey “reformist” governor.

Wilson. At this point (1913) America had as its president a former professor and Princeton University president (1902-1910), who had also just served briefly (1911-1913) as a New Jersey “reformist” governor.

The intellectual nature in Wilson disliked rather deeply the idea of the constitution’s “checks and balances system,” designed to make sure that power never concentrated itself in any particular part of the federal structure. Wilson was fully convinced that America would be best led by a very strong leader, which he made clear in his 1908 Constitutional Government of the United States. But that was very revealing of his own personality, which as president of Princeton, his autocratic style came to embitter deeply the professors there, which is why he ultimately left that position to become New Jersey governor.

America’s new love affair with “democracy.” He was also a strong supporter of the idea of “democracy,” and certainly supportive of the 16th and 17th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution which went into force the year that he took office as president (1913). The 16th Amendment authorized Congress to tax directly the American people, the national government no longer having to rely on state support to finance its programs. And the 17th Amendment now had Senators being elected to office by the people rather than by being chosen by the states (formerly either by governors or state legislatures).

Both of these amendments were put forward under the promise that this would help clear up the corruption typical of some of the state governments, by placing more power in the hands of national leaders in Washington, leaders put there by the people and financed directly in their programming by the same people, and under their clear watch. But such Democratic Idealism was soon to discover that political corruption merely goes where the money and power go. And transferring such money and power to Washington only meant that those individuals and groups driven by greed and corruption would now find it more advantageous to play their games in Washington.

Ultimately, all of this “democracy” depended deeply on the moral character of the people themselves, but also most importantly on the moral character of their leaders, and their ability to hold to that moral course in the face of the games that people of power like to play with them. Historically speaking, that kind of strong morality has always been hard to cultivate … and to maintain. And it does not just happen “naturally.” It requires a society, from families all the way up to empires, to instill a deep sense of social-moral self-discipline in those responsible for its direction.

“DEMOCRACY” STIRS THE FIRES OF EUROPEAN NATIONALISM

We have already noted how the French attempted to produce in France a new republic, at just the same time that America’s new republic was entering into effect (1789), and how that French venture resulted in bloody catastrophe. We also noted that France was saved from this horrible mess only by Napoleon developing a citizen army, and sending his fired-up French nationalist troops to spend their energies in fighting the feudal armies of Europe’s surrounding dynasties. This formula of “nationalizing” his own army was so successful that the French were able to push across all of Europe, reaching even all the way to Moscow in Russia in 1812.

The fires of nationalism. But in the process, Napoleon’s amazing success ultimately forced these opposing dynasties to have to call on their own citizens to come to the defense of their homelands, under something of an ethnic or nationalist appeal.

These dynasties of course were messing with fire. And they hoped to put that fire out once they had used it to crush Napoleon and his French. But those nationalist embers continued to burn below the surface, and the post-Napoleonic dynasties (ranging from Spain to Russia) were not sure what to do about the matter.

Indeed, in Italy and Germany, where previously there had been no nationalist government to unite a deeply divided Italian and German people, there arose a clear sense of deep necessity to unite “nationally” on the part of various political leaders, resulting finally in the coming together of a new Italian nation (1860) and a new German nation (1870).

The Germans make the creation of the German Empire official – 1871

Meanwhile, in Western Europe, in places like Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia, something like “popular” government was growing step by step simply as a matter of what was increasingly understood by the politicians supporting dynastic governments, and even by the dynasties themselves, as a necessary piece of political “progress.” After all, at this point, “progress” was the byword for everything that had to do with human dynamics, whether political, economic, or social.

And indeed, drawing the masses of commoners into the political game once played only by a small ruling class, greatly energized the whole political process.

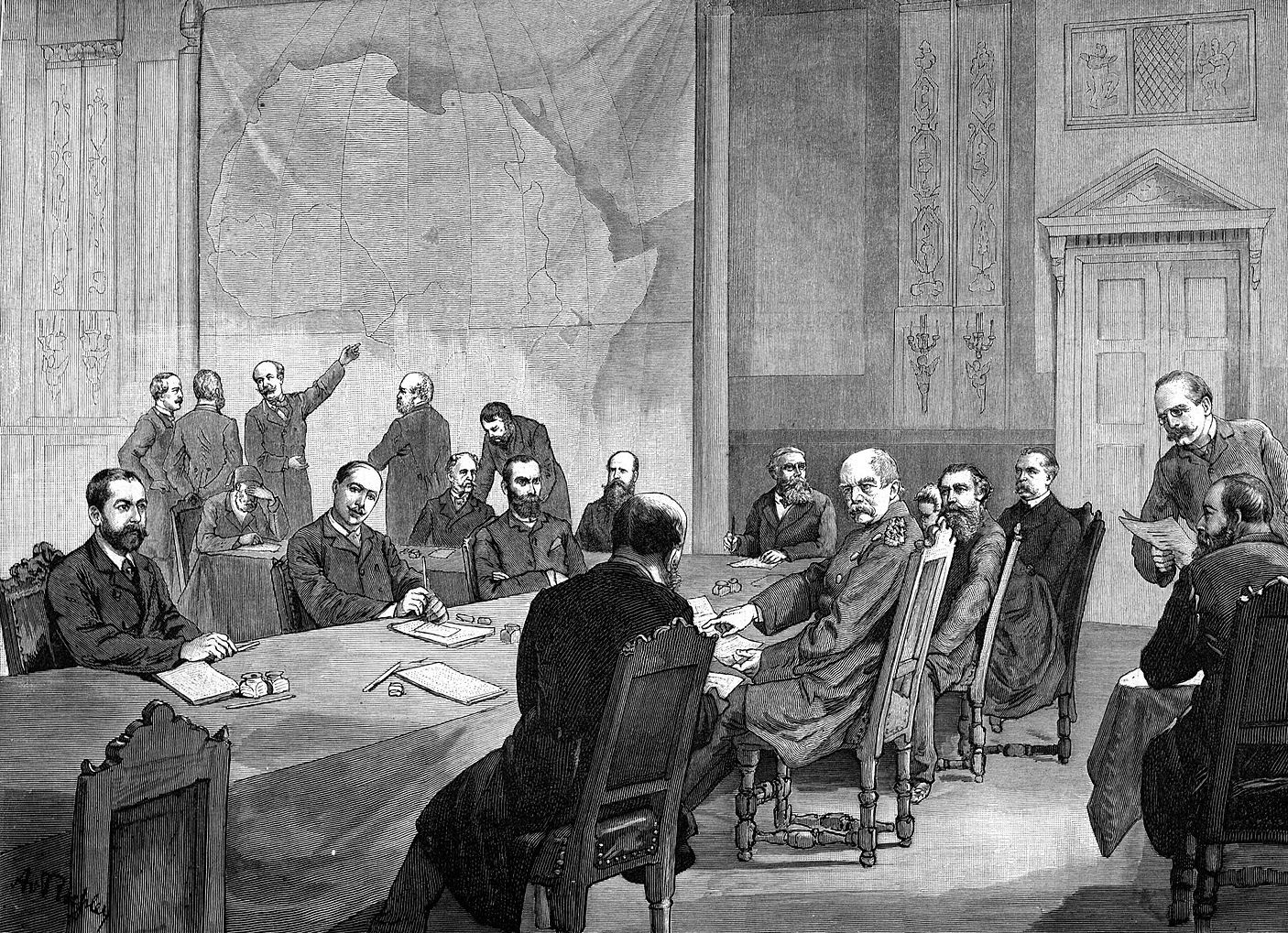

Imperialism as a distraction. In post-Napoleonic Europe, much of that energy was finding itself very useful in being put to work overseas in building European empires presiding over Asian and African societies. Sadly for both Asia and Africa, these societies were in no shape to fend off this huge amount of European power (joined eventually by American power) seeking to control them. Thus it was that Africa was carved up into various English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Belgian and German imperial territories. India fell largely under English colonial rule and Southeast Asia under French and Dutch rule. And China, thanks to British and American insistence, was held by no particular European power, but instead by all of them jointly!

The Berlin conference 1884-1885 – carving up Africa among the European powers

The Turkish disintegration. Then there was the problem closer to home, Ottoman Turkey. The Turks had long held the Arabic-speaking portion of the eastern Mediterranean and Southeastern Europe (the Balkan Peninsula) as part of their huge empire. But the Turkish ethnic portion of this huge empire was quite small. Non-Turkish Arabs in the empire remained fairly compliant in their Turkish dependency, because they shared the Muslim faith with their Turkish masters. But Turkish-held Europe was resentful of that same dependency status, and, noticing a weakening of Ottoman rulership, began to rebel against that Turkish domination, starting with the Greeks, but soon extending to the Bulgarians, Serbs and others of the Balkan Peninsula.

This brought the nationalist-imperialist urge closer to the heart of Europe. Europeans now found themselves drawn into the contest, not only over the matter of supporting the Turks (the Germans and British were of a mindset to do so) or opposing the Turks (the Russians were adamant Turkish opponents), but in supporting one or another of Europe’s rising Balkan states. These rising Balkan states were now finding themselves also in strong opposition to each other as they tried to carve out their newly independent societies in the post-Turkish Balkan Peninsula. Trouble was now brewing right there in Europe itself.

THE “GREAT WAR” (WORLD WAR ONE) 1914-1918

War breaks out in the European heartland (1914). And so things exploded in 1914, when a Serbian nationalist killed the heir-apparent to the Austro-Hungarian throne on his visit to Serbia, the Austro-Hungarian duke’s visit originally intended to bring Serbia into a widening Austrian orbit. War against Serbia was ultimately declared by Austria, Russia jumped to defend Serbia, Germany jumped into the conflict to defend Austria, France linked up with Russia and Serbia as allies, and even Britain joined the conflict as a French-Russian-Serbian ally. And all of this was achieved in a matter of days at the beginning of August 1914.

And now the slaughter was on in the conflict between these two evenly matched contending groups. And once underway, no one knew how to bring the mess to a halt, nationalist sentiments now running at fever pitch. Everything boiled down to nationalist pride. No one wanted to be a loser. Consequently, they threw at each other everything they had by way of available manpower and material-technological support.

British soldiers being gassed at the Battle of Ypres – 1915

At first, American president Wilson saw no reason to get involved in the mess, although the whole thing made for new American trade opportunities with both European societies, both groups needful of anything and everything that America could sell them. Thus America got really upset when the British intervened by way of a naval blockade to stop the sale to Germany of America’s “neutral” products. But even more irritating were the similar efforts to block American shipments to Britain and France by the German navy, by means of the new submarines, which meant that American ships sunk by such U-boats (Unterseeboot) could not offer surviving sailors any rescue (as could British ships). Under American threats of strong reprisals, the Germans finally backed off in conducting such attacks. But then in early 1917, with Germans facing starvation because of the British blocking of greatly needed food coming to Germany from America and Latin America society, the U-boat attacks were resumed in order to break the British blockade. Americans were furious.

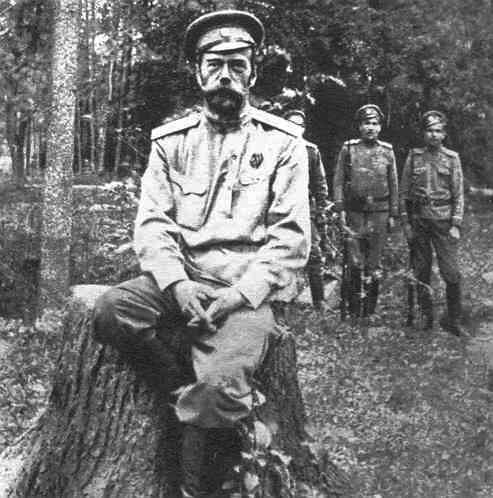

At the same time (early 1917), the Russian war effort simply collapsed. Russian troops were exhausted from having to fight Germans and Austrians with no weapons at hand. And the Russian Tsar (Emperor) was exhausted as well because of Russia’s poor showing in the war. The Tsar simply walked off the job, ultimately leaving the job of governing Russia during this horrible war to a newly assembled government, one which supposedly was to take on more of a democratic character.

Tsar Nicholas under arrest – 1917

(He and his family would be secretly executed in July of 1918)

Wilson takes America into the war (1917). For Wilson, that was the clincher, because in his eyes the battle was not just among contending nationalities, but instead a great moral struggle between “democracies” (England, France and now supposedly Russia) and “autocracies” (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey). And now he was ready to come into this war, on the side of the democracies. For Wilson, the war now appeared to be a crusade for democracy.

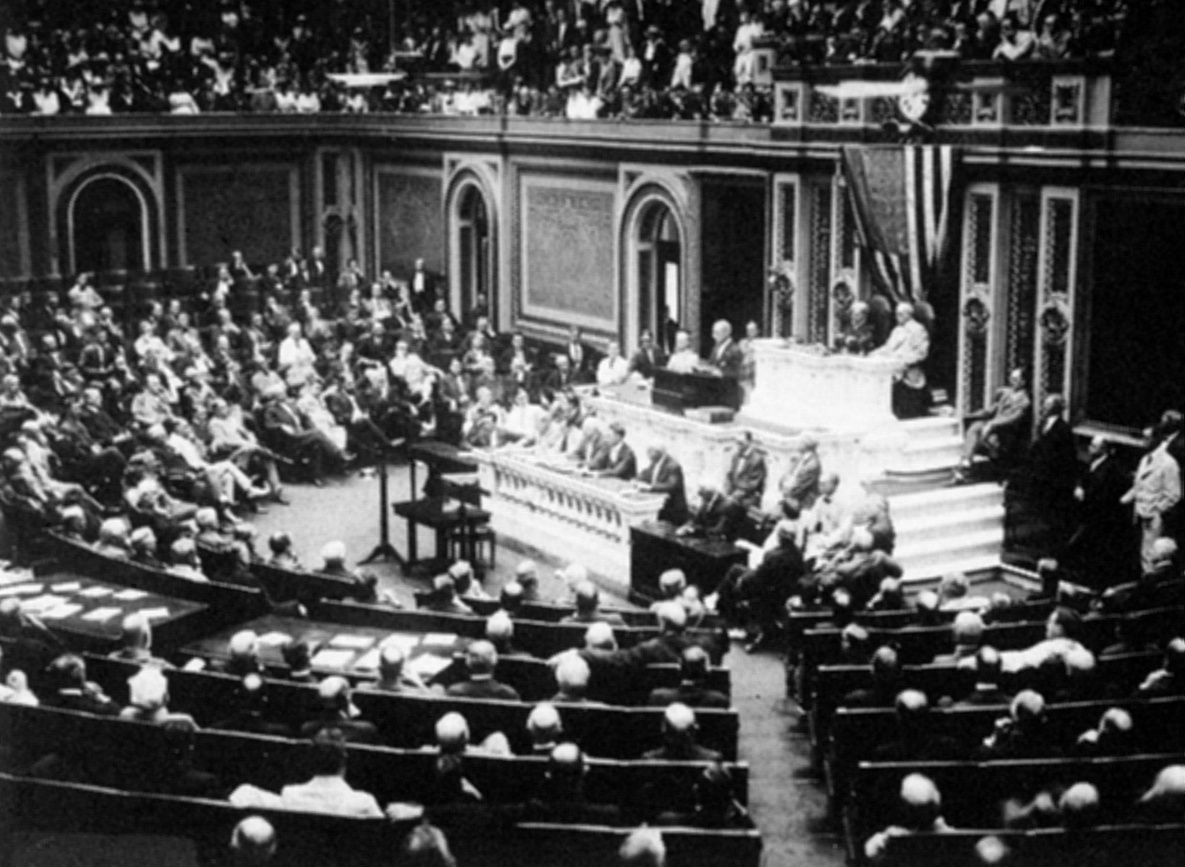

Wilson calling on Congress to declare war on the “autocracies” – April 1917

This of course was a gross oversimplification of the actual dynamics behind this horrible conflict. “Autocratic” Germany was headed by a dynasty. But so was “democratic” Britain. Britain had a parliament in part elected by the people. But so did Germany. And Germany had instituted a number of very progressive social policies that other European countries had yet to match.

And Russia was by no means now suddenly a democracy. The Russian people themselves had no idea what democracy was about, and were totally unprepared to take up the political responsibilities that democracy truly requires.

But Wilson saw what he wanted to see in all this, and now jumped America into the war (April 1917), thus sending thousands of young Americans off to fight a war, one that had nothing to do with democracy, or its establishment anywhere. Thousands of American soldiers were called on to fight, and possibly even die, in promoting this Wilsonian cause, this Wilsonian dream, a dream that was far, far removed from reality. And so that’s exactly what happened. Thousands of young American men would die as a part of Wilson’s democratic crusade.

Of course America was initially unprepared for such an engagement, possessing only a small army, used merely for what might be termed “police actions” in trying to “protect” the government in the Philippines put in place there since the ending of Spanish rule, and in also protecting the border with Mexico against the Mexican raids (principally Pancho Villa) coming across those borders. To go up against Germany in Europe, it would take some time to get a serious military force organized.

However, fired-up Americans were quick to join the military … and to buy the countless war bonds (loans to the government) needed for the government to be able to pay American industry for the needed ships, canons, guns, uniforms, etc.

But it would not be until the following spring of 1918 before America had enough newly-trained troops ready to make a serious impact on the war going on in Northern France.

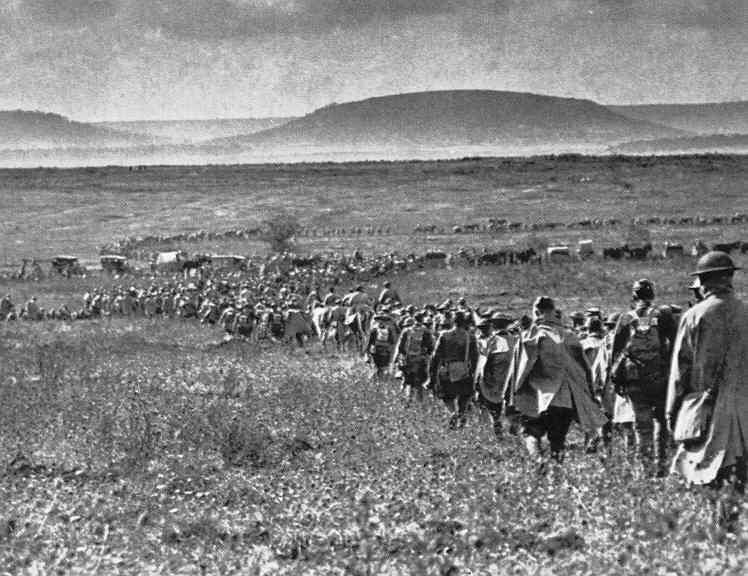

At first, the British and French allies wanted American troops to be slipped into their fighting units as “replacements.” But American commander General John Pershing insisted that they be positioned as separate American military units at various points along the battle front reaching across northern France. In the meantime, the exhausted Russians negotiated a separate peace with the Germans, the Germans being most eager to move troops from Russia to France in anticipation of the soon-to-be arrival on the scene of American troops. This they did, and in March of 1918, repositioned Germans undertook a major offensive against the British and French. But the latter held firm, and the effort merely exhausted the Germans.

At first, the British and French allies wanted American troops to be slipped into their fighting units as “replacements.” But American commander General John Pershing insisted that they be positioned as separate American military units at various points along the battle front reaching across northern France. In the meantime, the exhausted Russians negotiated a separate peace with the Germans, the Germans being most eager to move troops from Russia to France in anticipation of the soon-to-be arrival on the scene of American troops. This they did, and in March of 1918, repositioned Germans undertook a major offensive against the British and French. But the latter held firm, and the effort merely exhausted the Germans.

Then American troops finally made their arrival in April. They took positions at various points of the front (Saint-Mihiel and Belleau Wood, for example) and then made their move against German troops, Germans now trying to fend off this new energy on the part of the French-British and now American allies. The fighting was fierce. But the Germans could no longer hold the line, and began to fall back. It was clearly over for the Germans.

Americans heading to the front at St. Mihiel – 1918

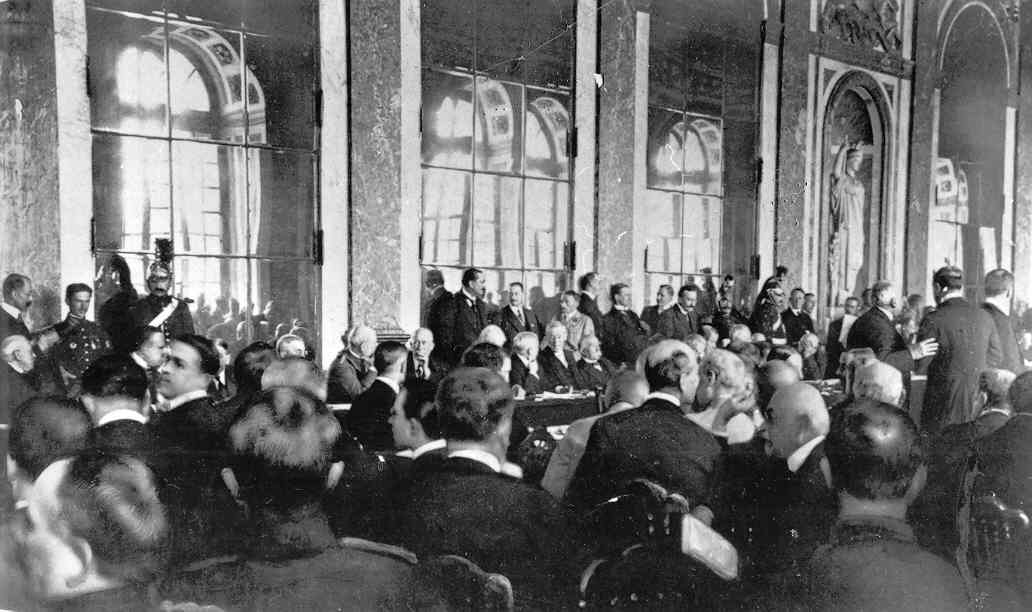

“Peace” (November 1918). Consequently, in November of that year, an exhausted Germany and its allies, Austria-Hungary and Turkey, simply surrendered. Now Wilson would supposedly have a chance to see his democratic dream come to reality.

But that simply was not going to happen. Other than the Kaiser’s dynastic government being overthrown in the last days of the war by exhausted, angry German rebels, and being soon replaced by a new republican government based at Weimar, nothing else developed along Wilson’s “democratic” lines. The Austrian Empire was broken up into a number of individual countries, countries that perhaps had some possibility of developing “democratic” social instincts in the future. The Turkish Ottoman Empire was also broken up into a number of individual countries, which however had virtually no likelihood of developing as democracies. This then gave both Britain and France the excuse to take these countries under their wings as “mandates,” in essence expanding the British and French Empires deep into the Middle East, a political move not greatly pleasing to Wilson, who had presumed that the war was all about democracy, not empire.

Quite tragically, this move to “democracy” also merely plunged Germany into massive political confusion, and a nasty civil conflict at home (1919-1923). And most tragically, it also produced a lot of resentment on the part of the Germans about how this “democratic” government ultimately came into being only through German defeat. Hitler would later play this sentiment to his own political favor, and to a lot more destruction inflicted on Western society by a deeply resentful Germany.

Wilson’s wife Edith helping him do his work – 1920

In the end, Wilson came home in 1919 as an unsuccessful negotiator, and suffered a greatly damaging stroke that same summer (which Americans were prevented from knowing about). He would finish out his term in office with his wife basically having to cover for him.

One thing he actually contributed to the peace talks however was his League of Nations idea, an international organization designed to help its members develop the use of diplomacy rather than military in their relations, hopefully therefore making the horrible war they had just gone through to be “the war to end all wars.” Again, this League of Nations was the product of more Wilsonian Idealism, although numerous Western countries joined the organization.

But oddly enough, Wilson’s America did not join, as Wilson refused to compromise on any part of his proposed plan, even when the Senate (the portion of American government designed to decide such international matters) showed deep concern about turning its foreign policy, its right to protect itself, over to this international organization.

America’s decision to be virtually the only Western country not joining the League of Nations broke Wilson’s heart. Once again, tough political Reality (that he refused to work with) crushed the Idealism that governed Wilson’s spirit.

RECOVERY II (THE “ROARING TWENTIES”)

Deep postwar anguish

What would American society, but especially European society, do to come back from this insane disaster that the Christian West had just put itself through? Of course reactions would vary from society to society. But they all tended to be rather intense in nature. Coming out of this wartime disaster emotionally, spiritually, was not going to be easy. Europe had lost a good part of a rising generation of young men. And the ones who did survive would be scarred deeply by their wartime experience.

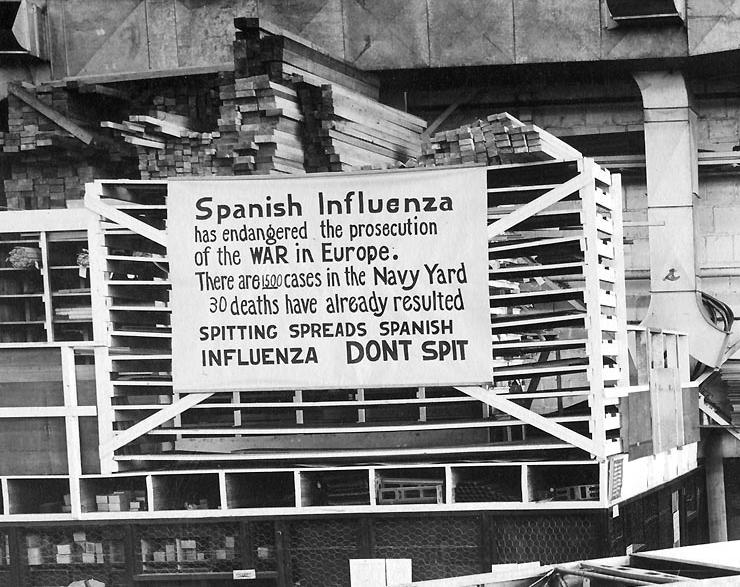

The Spanish Flu (1918). Then there was the matter of the Spanish Flu, which hit the world hard just as the war was coming to a halt. 16 million people had died during the war; but the Spanish Flu killed three times that number within mere months (late 1918). And many that survived the attack would nonetheless find themselves permanently crippled.

This then left the question: where was God in all of this? Clearly he had not started this war, nor seemed to be the cause of its end. And certainly he had not chosen to inflict the Spanish Flu on those millions of good people. But still, why had he not intervened?

Economic depression in rural America. Then too, economically speaking, the European national economies now found themselves at a horrible low. The end of the war most naturally shut down a good part of the industrial world so recently built around the material requirements of the war. And shifting to a peacetime economic order was going to take some time. Thus work for those returning from the battlefields was hard to find.

In this, America seemed to be, at first, the exception, in part because its military loss had been much less by comparison to the loss on the part of the European societies. Indeed, for the farming world, the huge profits they made on their food products sold to a rather farmerless Western Europe (young European farmers had become soldiers during the war) would continue to flow to America, at least for a couple of years after the war’s end.

However, when the European farm boys got themselves back working on their farms, the profitability of American farm production, built heavily on that export market, quickly faded away.*

American farmers had put themselves in deep debt during the war, because of the bank loans they had taken out to purchase all that new farm machinery and additional farmland. But these were loans that within a few years of the end of the war they were totally unable to repay. They would be most willing at this point to sell off some of that land, now that production had cut back so greatly. But who would want to buy that farmland from them? The value of the land now proved to be much less than the bank loans they still had to pay the interest on. Thus it was that bankruptcy hit rural America savagely. But it hit not only the farmers, it also hit the local banks, who found their involvement in supplying these farmers with those now unpayable loans rendering the banks themselves worthless.

Minnesota potato farmers finding life to be quite tough – 1920s

The onset of the Great Depression at the beginning of the 1930s is quite well-known to us (and we will have much to say about this further on). But most of us do not know that for rural America, that same Great Depression actually started ten years earlier, when it hit at the beginning of the 1920s. And recovery would be slow, and not great for rural America.

Again, where was God in all this?

Jazz Age urban America

Then there was urban America, which seemed to suffer none of the shortcomings experienced by rural America. Indeed, urban America seemed to enter some kind of party mode, where life was seemingly rich and exciting.

A Charleston competition in St. Louis – 1925

A big part of this was due to the way American industry quickly switched from military production to the production of radios, washing machines, and other household goods, but most importantly automobiles. The latter was partly a result of the policies of Henry Ford, who made his Model-T Ford priced at a level that even his own workers could afford one for themselves. When the Model-T was replaced by the Model-A in 1927, the number of Model-Ts that had been sold amounted to over 15 million!

But also under production during these “Roaring Twenties” was flashy clothing, cigarettes, and yes alcohol. In fact there was a great expansion of the (not so undercover) alcohol trade that went on despite – or even in deliberate defiance of – the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, which went into effect in 1919, outlawing alcohol sales. This was a law that a very traditional (mostly rural and small town) America had seen to impose on the country. And urban America found the new law to be something they were proud to ignore.

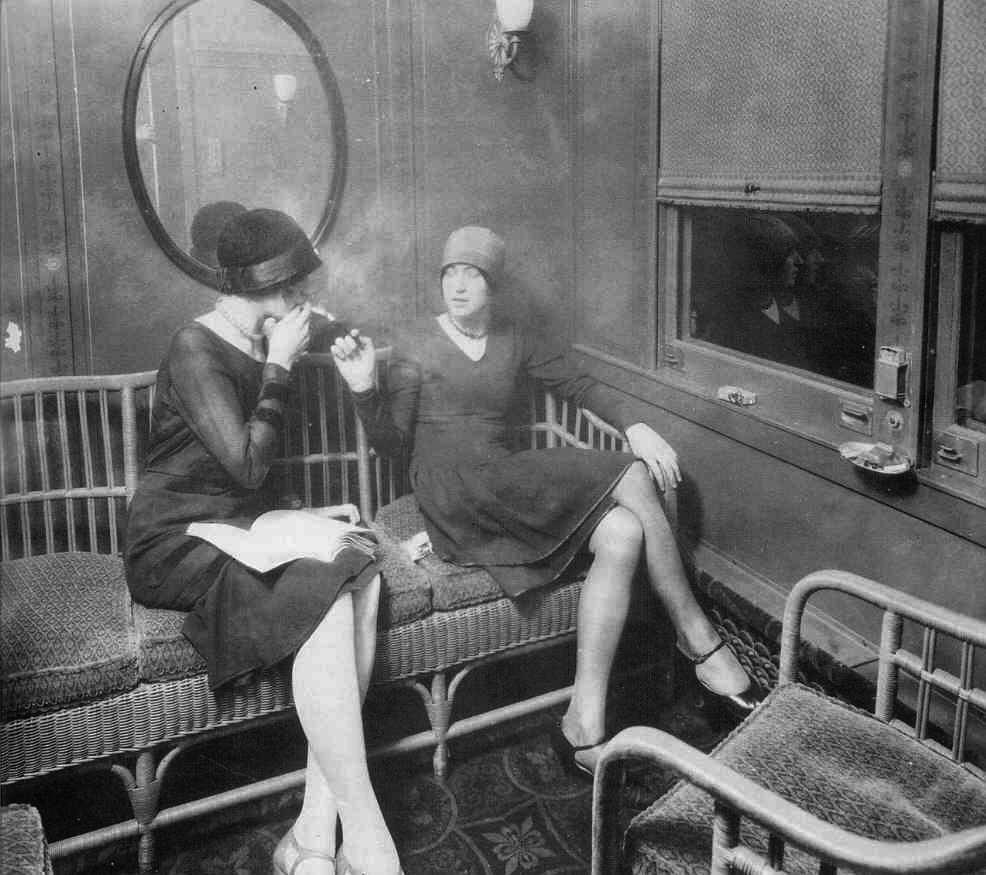

The wonderfully illegal partying at a 1920s “speakeasy”

Indeed, the “law” in general seemed to come into purposed disrespect by a newly “freed” postwar culture or spirit, a spirit found widely among America’s younger adults.

Another sign of the times was the entry into effect in 1920 of the 19th Amendment, opening the national vote to women in those states that had not already done so. The idea was that women no longer needed to rely on their husbands to do the speaking for the family. They could do that for themselves. In fact the idea was that they were free to do most anything for themselves, family roles no longer holding the paramount position that they had held formerly. A spirit of “individualism” was growing strongly in American culture, particularly among younger Americans.

Enjoying life in a train’s smoking car

The Scopes Monkey Trial (July 1925)

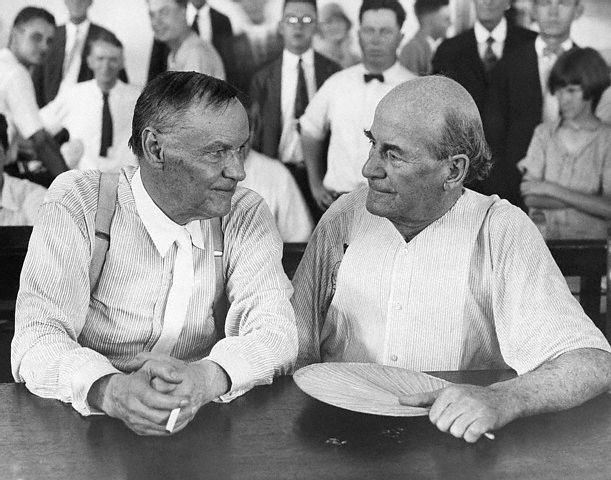

A sign of the times was the famous trial held in Dayton Tennessee over a state law that prevented Darwinism from being part of the teaching conducted in Tennessee’s schools. The trial all started as something of a stunt by some of the town’s leaders, who thought that contesting the law would bring some needed attention to the town. But the stunt became a national debate when the New York celebrity lawyer Clarence Darrow was brought in to defend the town against the law, and found strong support from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), in the ACLU’s effort to replace America’s traditional Christian worldview with Secular-Humanism as America’s new worldview.

Defending the “Christian” viewpoint, that God, not mechanics, stood behind man’s origins, was the old political warhorse William Jennings Bryan (formerly three times the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate). Bryan’s defense was that man was not the descendant of some earlier form of “monkey” (thus “monkey trial”), but was founded fully in his present form from the very beginning of his creation.

Darrow and Bryan

But actually his defense reached much more broadly than simply this matter of Darwinism. To Bryan, the case was really about how “science” had replaced Christian ethics (built on Christ’s love) with the laws of mechanics, loveless mechanics that had just proven themselves able to slaughter millions on the world’s battlefields. His closing argument (not presented at the trial itself but published soon after) is worth quoting because it is also highly prophetic. Most tragically, World War Two would soon validate completely Bryan’s warning:

Science is a magnificent force, but it is not a teacher of morals. It can perfect machinery, but it adds no moral restraints to protect society from the misuse of the machine. . . . Science has made war so hellish that civilization was about to commit suicide; and now we are told that newly discovered instruments of destruction will make the cruelties of the late war seem trivial in comparison with the cruelties of wars that may come in the future. If civilization is to be saved from the wreckage threatened by intelligence not consecrated by love, it must be saved by the moral code of the meek and lowly Nazarene. His teachings, and His teachings alone, can solve the problems that vex the heart and perplex the world.

Ultimately this trial truly revealed the deep moral-spiritual division America had fallen into. Bryan’s view was strongly supported from American pulpits across the country, while the major Liberal (Secular-Humanist) “up East” newspapers treated the matter as a sad joke, sad because any reasonable person could see how the Tennessee law was the dangerous tool of fools.

In the end, no one truly won or lost the case. The battle of worldviews would simply continue … to be present constantly in serious moral-spiritual questions that the country would continue to face (even down to today).

Moral-spiritual America in the 1920s

The “Prohibition” culture generated by the 18th Amendment served only to deepen this “traditional” versus “progressive” social divide afflicting America. Notorious were the gangs that made huge profits off the sale of the illegal alcohol, not only defying the law, but defying all moral sense needed by American society. Particularly famous, treated almost as heroes by “progressive” America, were the likes of Chicago gangster Al Capone, Capone known for his murderous hand in the wars going on between corrupt gangs.

St. Valentine’s Day gang killing in Chicago – 1929

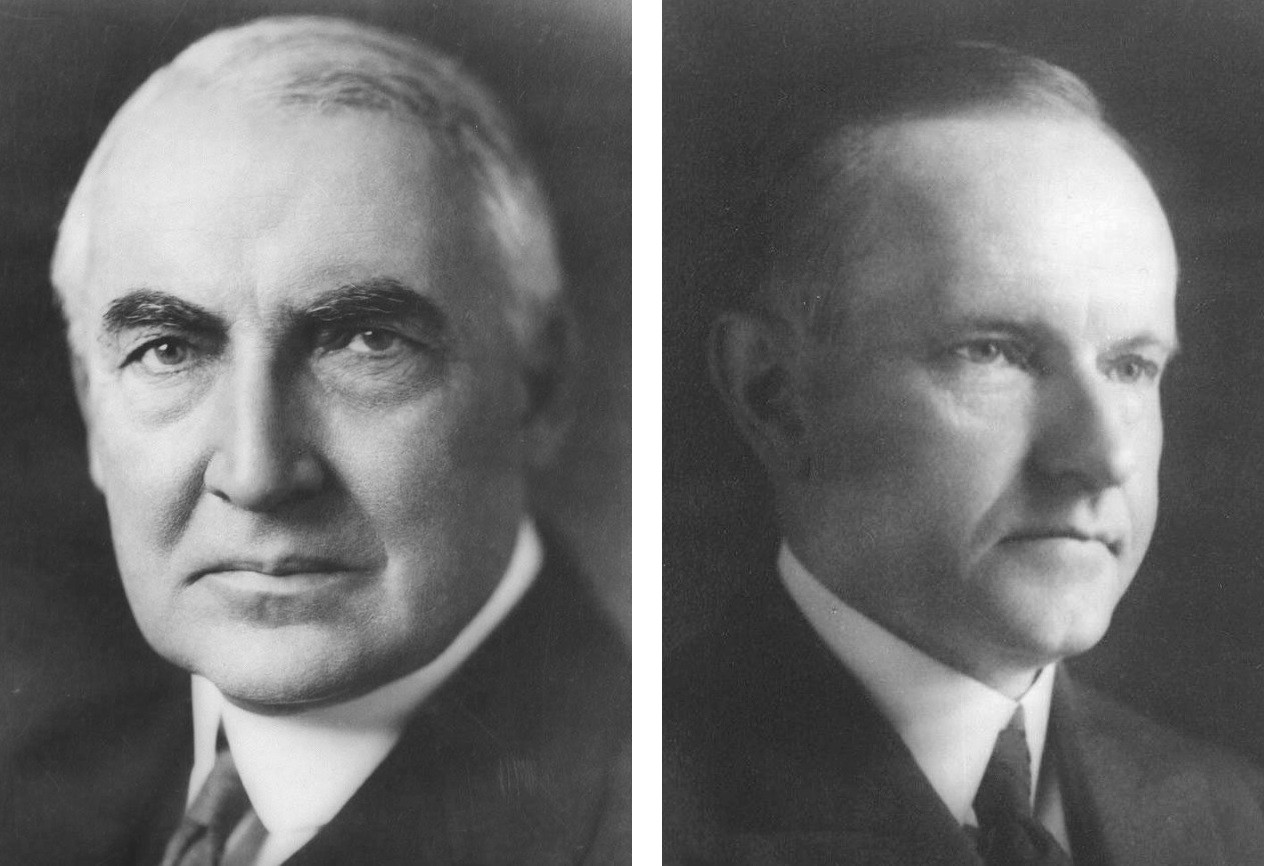

But that same moral decline was to be found in the presidential offices of William Harding, not so much in the president himself, but certainly in the offices below him that he seemed unable to discipline.* Sadly he suffered a heart attack and died after only two years in office (1921-1923) while taking a trip across the country to present his side of the moral questions that were rising around him.

It would finally take the strong Puritan moral character of his Vice President (thus now President) Calvin Coolidge to inspire America to head back towards its former, quite strong, moral foundations. And indeed, America would settle down (somewhat) under his quiet but firm leadership.

Harding Coolidge

As for Christian America, America’s churches at least, the 1920s would generally prove to be a huge disappointment. There was much hope placed in an Interchurch World Movement, numerous Christian denominations coming together immediately after the war to try to support the Wilsonian dream of a new world of peace and wisdom, the churches seeing Christian mission as a vital part of that dream. But just like the post-war fast-fading of Wilsonian Idealism, so the missionary spirit faded, and the organization failed to find the funding it was expecting in order to carry out its proposed mission. It would still continue forward, but at a much lower operational level than originally planned.

Then too, the bitter Liberal versus Fundamentalist battle in the American theological centers would not lessen. The initial Fundamentalist supremacy was finding itself, step by step, being replaced by a rising Liberal supremacy, as pastors switched loyalties, or were simply driven from their particular denominations. Often it was not a pretty scene.

Equally sadly for traditionalist America, across the nation (and the Western or “Christian” world as well) the 1920s would see an alarming drop in church attendance.

But Liberal America was running into its own moral-spiritual problems, in that all this moral-spiritual freedom was leading individuals to find themselves without purpose as they took on life’s challenges. The “Jazz Age” often found itself not truly free, just simply empty.

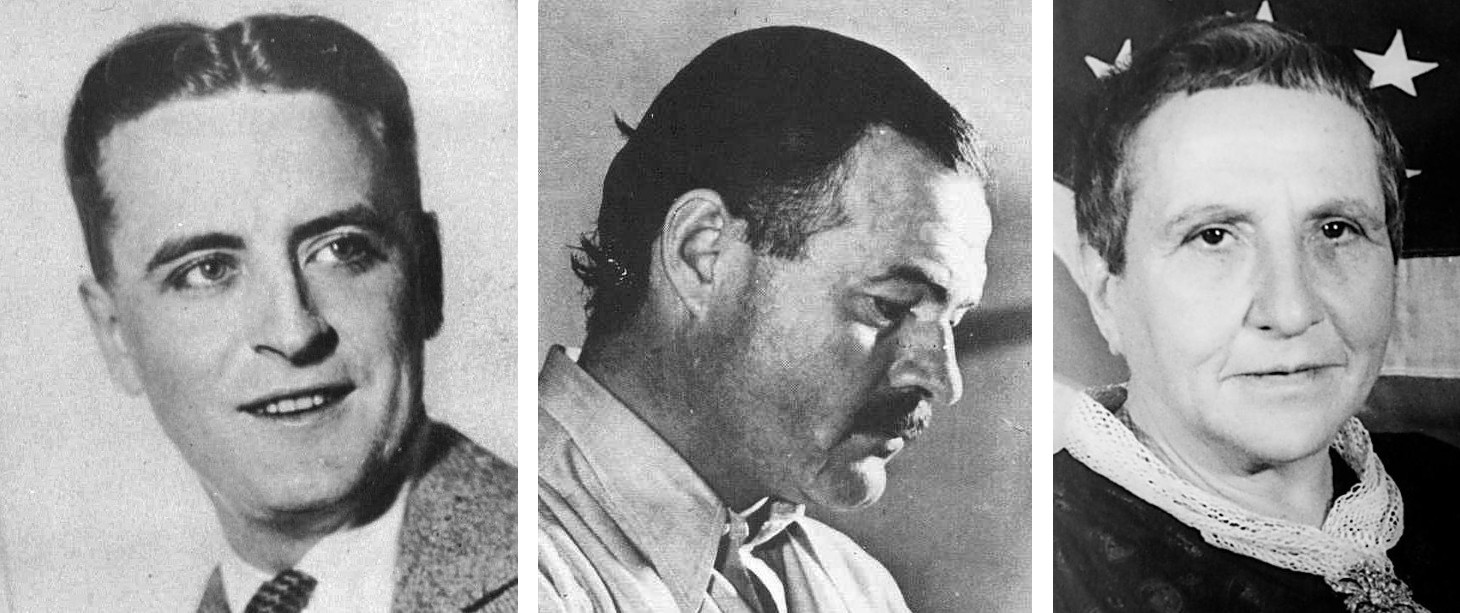

The “Lost Generation.” A classic expression of this spirit was found in a work of one of America’s great authors, F. Scott Fitzgerald: his The Great Gatsby (1925), where a group of quite fancy Jazz Age individuals coexist in a world of conflicting sexual relations, but also a world which ends in Gatsby’s murder, depicting just such a world without any particular meaning or grand purpose. In a way, Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926) was an attempt to impart some element of meaning and purpose to the Jazz Age world of the “Lost Generation,” a term American Gertrude Stein used in reference to the large group of American expatriate artists and intellectuals that she hosted in Paris, who gathered there in the hope of finding such meaning and purpose. Whether Hemmingway succeeded or not in his effort is debatable.

Fitzgerald Hemmingway Stein

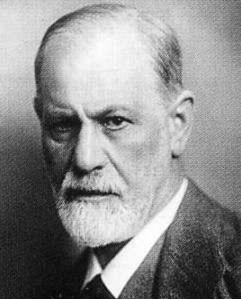

Freud. Not helping the matter much was the Austrian psychologist, Sigmund Freud. Freud’s “science” was actually merely Freudian opinion on matters of how and why the human mind works as it does, Freud hoping to bring some degree of rationality to such matters. He loved to see human instinct as shaped by very early sexual urges that get repressed during childhood … which good counseling can release the person from. That was a theory that appealed greatly to people looking for the “cause” of their behavior, even though there was no truly “scientific” basis on which Freud’s theories were derived.

Freud. Not helping the matter much was the Austrian psychologist, Sigmund Freud. Freud’s “science” was actually merely Freudian opinion on matters of how and why the human mind works as it does, Freud hoping to bring some degree of rationality to such matters. He loved to see human instinct as shaped by very early sexual urges that get repressed during childhood … which good counseling can release the person from. That was a theory that appealed greatly to people looking for the “cause” of their behavior, even though there was no truly “scientific” basis on which Freud’s theories were derived.

But he also loved to attack the West’s traditional religions, but especially Christianity, as being nothing more than tragic neurosis, useful illusions that we feed ourselves in order to find some degree of comfort in the face of a very difficult existence.

But then, how was Freudian psychology any less the sort of thing that he accused traditional religion of being, namely, just a set of useful ideas offering some degree of comfort in the face of a very difficult existence?

But thus it was that he was able to gather into his realm a large number of Jazz Agers, practicing Freud’s very “rational” religion.

THE BROADER WORLD DURING THE TWENTIES

Russia

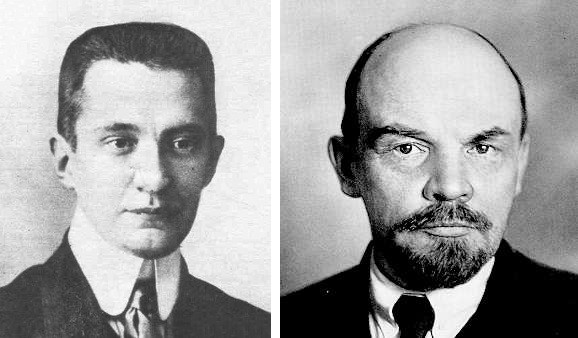

Russia would, as a follow-up to the collapsed Tsarist regime in early 1917, most definitely not go down the road that the Idealist Wilson had dreamed it would. The new Provisional Government of Kerensky foolishly assumed that what formed the foundation of this political changeover was the people’s enthusiastic support for a new democratic government. Actually, they just wanted out of the war, and failed to come to such support of the new government when it became clear that this government was going to continue to pursue the war, in joining with Wilson in his “crusade for democracy.” Some did join, many of “middle-class” Russia. But Russia’s industrial workers refused to go down that road, and formed a party under V.I. Lenin’s Marxist leadership (Russia’s “October Revolution” in late 1917), Lenin committed not only to getting Russia out of the war but also to setting up their own “Communist” society governed by workers’ councils (soviets).

Kerensky Lenin

When Lenin was fully able to take command of the strategic soviets of Petrograd and Moscow, and then in December of 1917, through his envoy Leon Trotsky, get an agreement with Germany ending the war between the two powers, Lenin’s Communist party, soon identified as the “Reds” (their flag), found themselves more securely in power. But still resisting them were the “Whites,” a loose coalition of middle-class “democrats” and former Tsarist supporters … as Russia now became caught up in a vicious civil war.

At this point, Wilson, along with the British (and others), sent troops to Russia in July of 1918 to aid the White coalition in its fight with Lenin’s Reds. But it soon became apparent that politically, as well as militarily, this was far more complicated a matter than Wilson had expected. He thus gave up the effort (as eventually did the other allies) and withdrew his American troops from this Russian civil war in July of 1919 – a war which Lenin and his Communist Red Army would eventually win (1921-1922).

Actually, Lenin soon backed down a bit in his Marxist purity, acknowledging with his “New Economic Policy” Russia’s need to continue to work a bit with Russia’s entrepreneurial talents (the “capitalists”) to get the Russian economy back up and running. But he was, at that point, a sick man, and died in 1924.

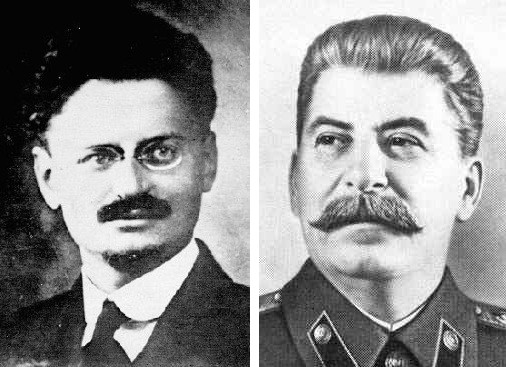

Soviet Russia then fell into a bitter contest for leadership, Lenin’s associate Trotsky being the presumed leader. But Joseph Stalin busied himself working secretly to put his followers in positions of power wherever he could, and, in openly opposing “Trotskyism,” one by one have his opponents eliminated.* Then when in 1928 he was so bold as to take command of the Soviet economy with his Five-Year Plan for government-directed industrial development in Russia, he found himself unopposed. He was clearly Soviet Russia’s new leader (dictator actually).

Tragically, this cost the lives of millions of Russians when Stalin shifted the foundations of the Russian economy from agriculture to heavy industry, producing starvation when the peasants resisted the turnover of their lands and herds to the Soviet authorities now ruling the land (“collectivization”). But there was nothing they could do to protect themselves, Stalin having put deep fear in the hearts of anyone not carrying out his orders.

Italy

Then there was Italy, a country stung by its poor performance in the war. The Italians had finally entered the war in 1915 on the British, French and Russian side, and subsequently had done very poorly against an Austro-Hungarian advance along the northern Italian front. This undercut deeply the country’s support for its national leadership, giving the ambitious journalist Benito Mussolini the opportunity to make a postwar move against Italy’s leadership, encouraging a band of his “Fascists” to march on Rome in October of 1922, and convince the King that what Italy needed was true leadership, the kind that Mussolini presumably offered. The king yielded, and Italy consequently found itself under Mussolini as their Duce (Leader) and his Fascist Party, a party increasingly backed up by a growing number of Fascist “Black Shirts,” paramilitary types ready to strike fear in the hearts of anyone so bold as to oppose, or even question, the leadership of their Duce. So Italy too had come under some kind of political dictatorship.

Then there was Italy, a country stung by its poor performance in the war. The Italians had finally entered the war in 1915 on the British, French and Russian side, and subsequently had done very poorly against an Austro-Hungarian advance along the northern Italian front. This undercut deeply the country’s support for its national leadership, giving the ambitious journalist Benito Mussolini the opportunity to make a postwar move against Italy’s leadership, encouraging a band of his “Fascists” to march on Rome in October of 1922, and convince the King that what Italy needed was true leadership, the kind that Mussolini presumably offered. The king yielded, and Italy consequently found itself under Mussolini as their Duce (Leader) and his Fascist Party, a party increasingly backed up by a growing number of Fascist “Black Shirts,” paramilitary types ready to strike fear in the hearts of anyone so bold as to oppose, or even question, the leadership of their Duce. So Italy too had come under some kind of political dictatorship.

What Mussolini planned to do to build a stronger Italy was never clear. Aside from the fanfare that accompanied Mussolini’s frequent public appearances, little seemed to change in Italy. Ultimately, the Italians seemed content to simply live life locally (as they had for centuries), and politically quietly.

Germany

Under the terms of the peace treaty signed in 1919 in Versailles, Germany’s new government based at Weimar (thus “Weimar Germany”) was virtually disarmed, forced to pay huge reparations payments to the allies for its role in the war, payments that Germany in no way could afford.

Somehow life was expected to continue on a somewhat normal basis for “democratic” Germany. But it seemed that everything that the victors did (principally Britain and France, because America basically backed out of further involvement in European affairs) was designed to ensure that postwar Germany failed. And indeed, the violent civil chaos of this group fighting that group, which descended upon Germany after the war, made it look as if this was indeed going to be the case.

But the spirit of the Germans was quite strong, despite the political things going on around them even after the civil fighting settled down. The worst they had to go through was the devaluation of Germany’s currency, the mark − the printing of mass amounts of marks done in part to meet the impossible reparations requirements. But the devaluation of the mark brought it to such low value, that in January of 1923, the Weimar government announced that it could not continue making the reparation payments. In consequence, French and Belgian troops moved into Germany to take over Germany’s industrial region, to “guarantee” that those reparation payments continued. But the humiliation did not end there, because the mark continued to drop in value, so that by the autumn of 1923 the mark was not even worth the paper it was printed on.

A German using worthless marks to heat her stove

The German government finally took the action to revalue, and promise to hold, the German mark to approximately 4.2 marks to the dollar, by cutting 12 zeros off the currency! This finally stabilized matters. But the whole thing had ruined the life savings of all German investors, and left a deep bitterness in the German heart towards their government, and the foreigners who had been behind this catastrophe.

Taking advantage of this mood was Adolf Hitler, who had played his cards right in publishing his personal story, Mein Kampf (My Struggle) while briefly in prison for an attempted takeover of the Bavarian state by his small group of National Socialists or Nazis. Little by little he would expand his circle of supporters, the paramilitary Brownshirts or SA (Sturmabteilung) “storm troopers,” mimicking Mussolini’s Blackshirts and their bullying tactics. But Hitler would not achieve the political status he was seeking until the early 1930s.

AMERICA AND THE WORLD

Despite not having joined the League of Nations, this did not mean that America backed completely off the stage of international politics and diplomacy. But certainly America’s involvement was fairly cautious at this point.

Unlike its European allies, Britain and France, who saw “victory” in this war as bringing grand opportunities to expand their empires, for instance France and Britain taking huge Arab sections of the defeated Ottoman Empire into their own empires as “protectorates,” America played to the other spirit of the times: the desire indeed to ensure that there would be no more wars.

And it was almost an unquestioned assumption at the time that the best way to ensure that was to reduce greatly the size of the military that the various world powers were entitled to possess. This after all had been behind part of the understanding of why its was necessary to cut back the German military to almost a pointless size.

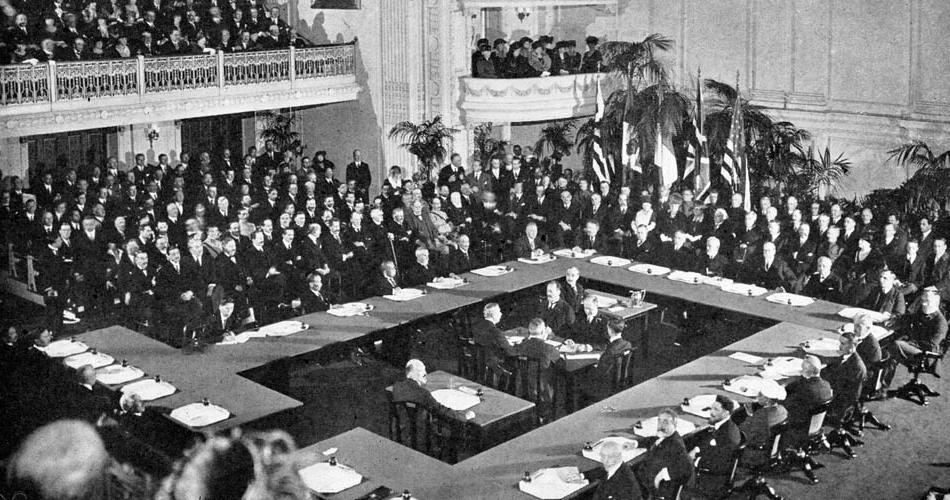

Following up on that spirit, it was America that would host a major international arms agreement at the Washington Naval Conference (winter of 1921-1922).

Various world powers met in Washington to go over plans to greatly reduce everyone’s military, and set precise limits as to the size of the military each would be allowed. And as the title of the conference suggests, the main emphasis was on the size and precise character of the navy that various naval powers agreed to limit themselves to.

Then there was the conference held in Locarno, Switzerland, (October 1925), in which America did not participate, but which it supported strongly. This brought Germany back into full diplomatic status (joining the League of Nations), as well as Britain and France’s other former opponents in the war … who all agreed that in the future they would seek diplomatic arbitration rather than jump to military action when issues developed among them. Thus the pacifist “Spirit of Locarno” seemed to have finally ensured that the world had come to its senses, and would never engage again in the kind of warfare they had just been through.

Thus supposedly the huge fear that Bryan had expressed earlier that year at the Scopes trial (the same fear which had brought about the Locarno Conference) had just been answered, but along purely “reasonable” rather that along Bryan’s “Christian faith” lines. Human Reason, not God, was expected to be the enforcer of this agreement. The world would soon see how that worked out for them.

America did jump back into the game again, this time as an agreement drawn up in August of 1928 between American Secretary of State Frank Kellogg and the French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand, termed the Kellogg-Briand Pact, agreeing to renounce all recourse to war as a means of settling conflicts. Soon the pact was joined by some 59 other countries (including Germany, Italy and Japan). Thus even Mussolini promised his support for this most noble idea, though soon he, and the Germans and the Japanese, would find themselves ridiculing the very idea of what the pact represented.

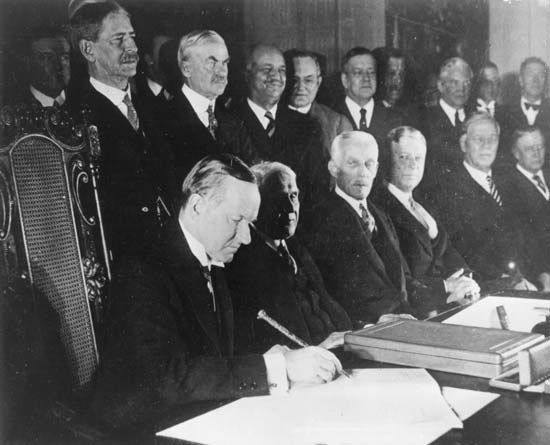

Coolidge signing the Kellogg-Briand Pact

Go on to the next section:

The Great Depression … and Rise of the Dictators