CHAPTER FIVE

CIVIL WAR … AND RECOVERY

AMERICA’S CIVIL WAR (1861-1865)

Things had become increasingly bitter over the matter of slavery, as the groups that identified themselves as “Abolitionist,” inspired deeply by the spiritual awakening that hit the country, were certain that this was a most evil practice, and needed to be ended before it brought the curse of God on the country. In response, the South dug more deeply into its own religious logic, claiming that God always intended that these African “Sons of Ham” were destined by God’s own decree to live eternally in service to God’s chosen people, namely to Whites such as themselves.*

Then there was the matter of the Nebraska Territory coming up for statehood. It would be divided into two states, Nebraska keeping the name for the northern portion and Kansas becoming the name for the southern portion. Nebraska was clearly going to enter the Union as a free state. But since the decision in 1849 to bring California into the Union on the basis of its own choice to enter as a free state, despite the fact that most of it lay well south of Clay’s line of division, the idea of letting the states themselves decide under what category they would enter the Union had become the new standard. But for Kansas, that would be a terrible matter, as the state was itself deeply divided between the two groups. Consequently, fighting broke out (mid-1850s), vicious fighting, something of an early startup of the coming Civil War.

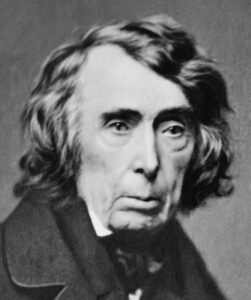

And deepening the pain of this very divisive issue was the Supreme Court and its Dred Scott Decision of 1857, in which Chief Justice Roger B. Taney succeeded in infuriating anti-slavery Northerners with his pro-slavery pronouncement declaring that no state had the right to free Blacks from slavery or to give them rights as citizens, the Constitution written to award those rights only to White Americans. The North ignored the decision, the South celebrated it loudly, and the nation divided even more deeply into two very hostile camps.

And deepening the pain of this very divisive issue was the Supreme Court and its Dred Scott Decision of 1857, in which Chief Justice Roger B. Taney succeeded in infuriating anti-slavery Northerners with his pro-slavery pronouncement declaring that no state had the right to free Blacks from slavery or to give them rights as citizens, the Constitution written to award those rights only to White Americans. The North ignored the decision, the South celebrated it loudly, and the nation divided even more deeply into two very hostile camps.

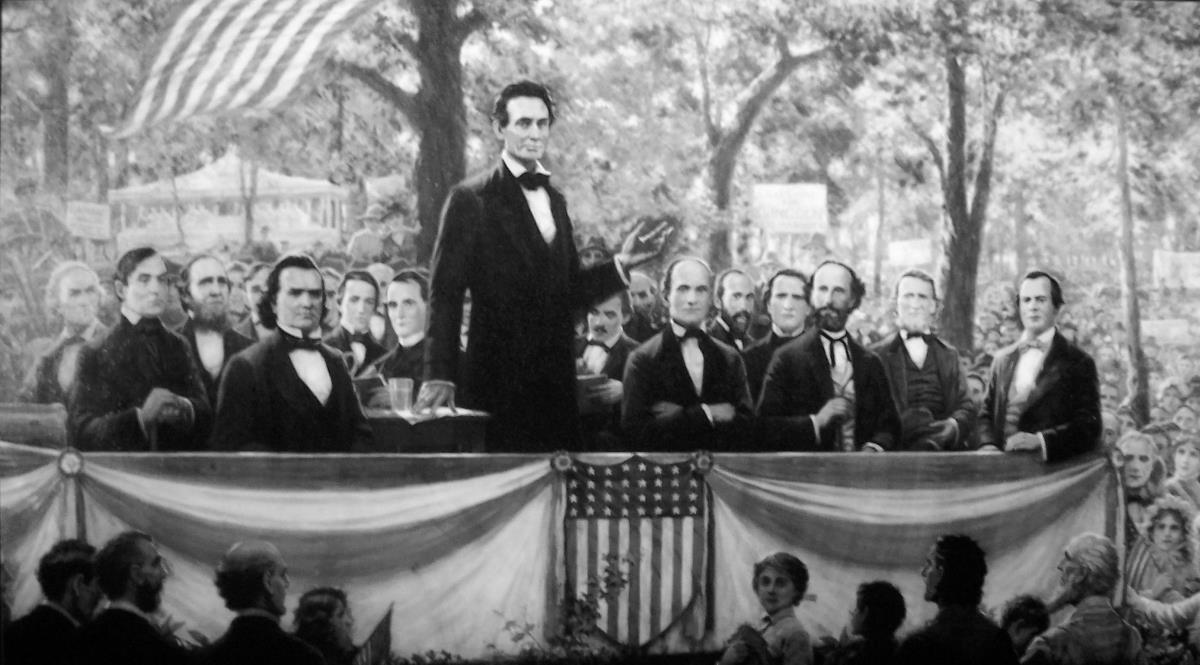

But what really set the war off was the election of Abraham Lincoln as the country’s new president in 1860. Lincoln, in his previous well-publicized Illinois debates with Senator Stephen Douglas (1858), had made it clear that it was time to bring slavery to an end in America. Britain had done so back in 1834 and France had done so in 1848.

But the South was most unwilling to bend on this matter, and before Lincoln could take office in March of 1861, South Carolina declared its separation from the Union (December 1860). And soon other Southern states did the same, coming together in February of 1861 to form their new Confederation of Southern states, with Jefferson Davis as their new president. And with South Carolina then in April firing on Fort Sumter (in Charleston’s harbor) to force the Federal forces located there to surrender the fort to the Confederacy, a war was on.

At first results were very mixed, because, despite the greater size of the Northern population and thus potential size of its military, the Confederacy actually contained a huge number of experienced soldiers, led by quite excellent officers. Ironically, Lincoln even at first asked General Robert E. Lee of Virginia to head up the Union army. But when Virginia chose to join the Confederacy (mid-April), Lee declined the offer. He would eventually prove himself to be an excellent commander for the Confederacy.

As for the Northern effort, it took Lincoln forever to find a similarly excellent commander. Consequently, the first two years of the war did not go well for the North. And complaints began to arise, supporting the idea of just letting the Slave South go its own way. Even at home, with his wife, Lincoln found growing pressure to just give up the effort. Multitudes of soldiers were dying, or being wounded horribly, with no gain to show for such a terrible effort.

But the American soldiers were themselves seemingly quite resolved to see the job done. Thus they went to war singing Julia Ward Howe’s Battle Hymn of the Republic:

But the American soldiers were themselves seemingly quite resolved to see the job done. Thus they went to war singing Julia Ward Howe’s Battle Hymn of the Republic:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord; He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored; He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword: His truth is marching on.

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps, They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps; I can read His righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps: His day is marching on.

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat; He is sifting out the hearts of men before His judgment-seat; Oh, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! Be jubilant, my feet! Our God is marching on.

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea, With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me. As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free, While God is marching on.

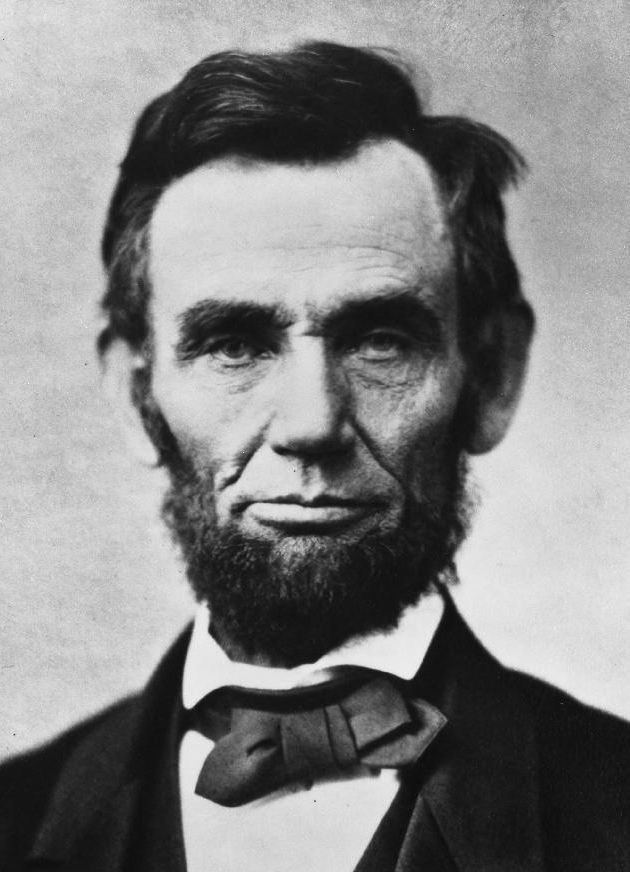

But it was also of enormous importance that Lincoln was truly one of America’s greatest leaders, which even members of his cabinet, who at first thought him to be no more than a clever country boy, had come to realize. Lincoln had a job to do. The Union had to be preserved, or a greatly weakened future awaited America, both North and South. And he still remained highly dedicated to the idea that both groups needed to get past the slavery issue and once again be joined together for the work ahead.

And he truly was a “man of God,” drawing ever closer to God for counsel as the situation became ever more difficult for him as national leader. Where else was he to go to keep the higher vision that he understood America to have been called to live by than directly to God himself?

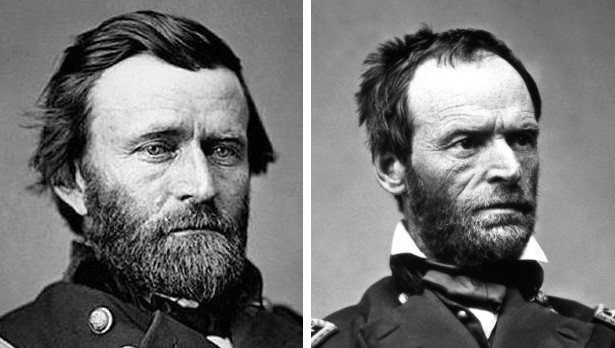

Finally, in Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, he got the military leadership the Union forces needed, the South found itself in steady retreat, and in the 1864 elections Lincoln was re-elected by Northern voters now fully appreciative of Lincoln and his leadership (no president had been re-elected since 1832!).

On March 4th of the following year, Lincoln addressed the nation with his inaugural address (found today etched on the interior North wall of the Lincoln Memorial in D.C.) leading into his second term in office, focusing the entire second half of the speech on the role of God and his judgment in shaping past events and future responsibilities, and thus the necessity of all Americans (both North and South) moving ahead together.

In the first part of this address he went over the origins of the war. He then continued:

Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.

Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.

He then explained that slavery was one of those offenses against God that God would allow, but only until such time as he was ready to exact his judgment, through the terrible war they had been experiencing.

If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.

He concluded:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with a firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

These were the words of a great leader, made ever wiser by the very impossibility of meeting the challenges he had facing him solely through his own intellectual abilities. Lincoln had learned to persevere in the face of massive uncertainty and huge risk, simply by trusting that he was merely a servant of the will of God himself and that it was up to God, not Lincoln, to bring the true and the good to bear in this Covenant nation that God himself had, centuries earlier, called into being. Indeed, this was the kind of wisdom that few American leaders after Lincoln were able to match even on a partial basis.

A month later (April 9th) Lee’s army was trapped at Appomattox, and with Lee’s surrender, the war was largely over. The Union had been saved.

RECOVERY … AND AMERICA’S SHIFTING MORAL PICTURE

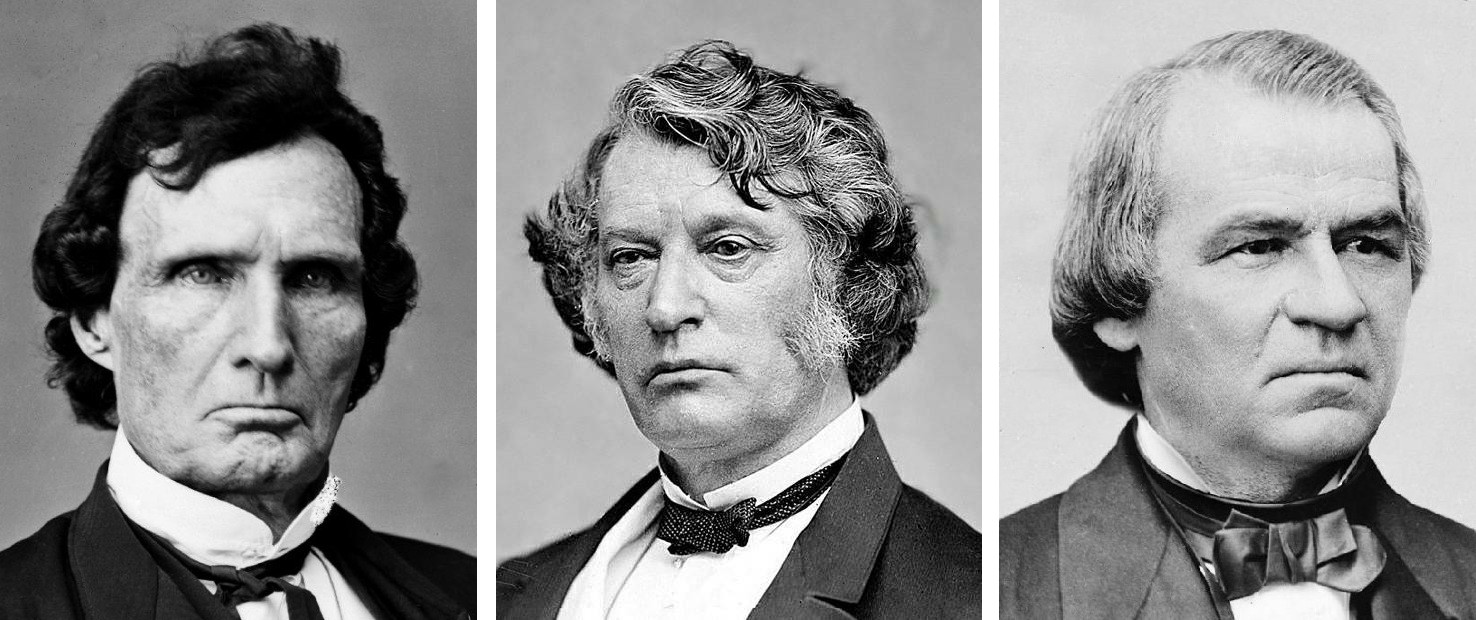

But less than a week later, both the North and the South would experience a great loss when Lincoln was assassinated (April 14th) by a Southerner who thought he was doing the South a great favor. But with Lincoln’s removal, vindictiveness and revenge, rather than healing, would fill the hearts of key Congressional leaders (principally the “Radicals” Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner), benefiting no one, North or South.

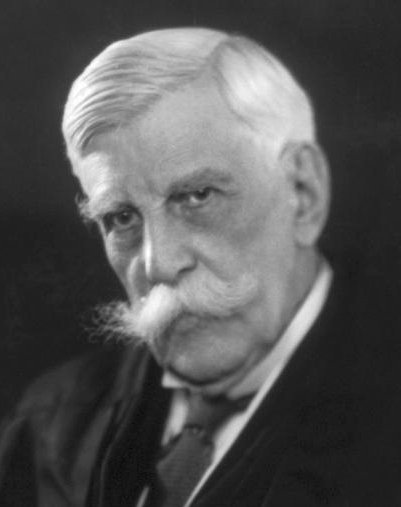

Stevens Sumner Johnson

Most tragically, the Radicals would most cleverly use the tool of “impeachment” to try to remove from power President Andrew Johnson (Lincoln’s Vice President) who appeared to them to be too pro-South, when in fact he was simply trying to continue Lincoln’s intention to restore the moral-spiritual union of a deeply divided country. The use of such a political weapon, intended only to be used in cases of treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors (something clearly Johnson was not guilty of), had not been attempted before. But ultimately, it failed, though only by the narrowest of margins. However, it did succeed in leaving Johnson powerless in his efforts to carry through Lincoln’s post-war plan for North-South reconciliation. Thankfully, this impeachment tactic would not be employed again, at least not for a long time afterwards.*

Ultimately, all the Radicals achieved in their self-righteous hunger for revenge was to end for the longest time (virtually a full century) the resolve of Southerners to reunite morally with their Northern partners. Instead, the behavior of the Radicals merely deepened the resolve of Southern Whites to preserve what they could of the social bondage held previously by Black Americans, something that they remained quite certain was a principle central to Southern culture.

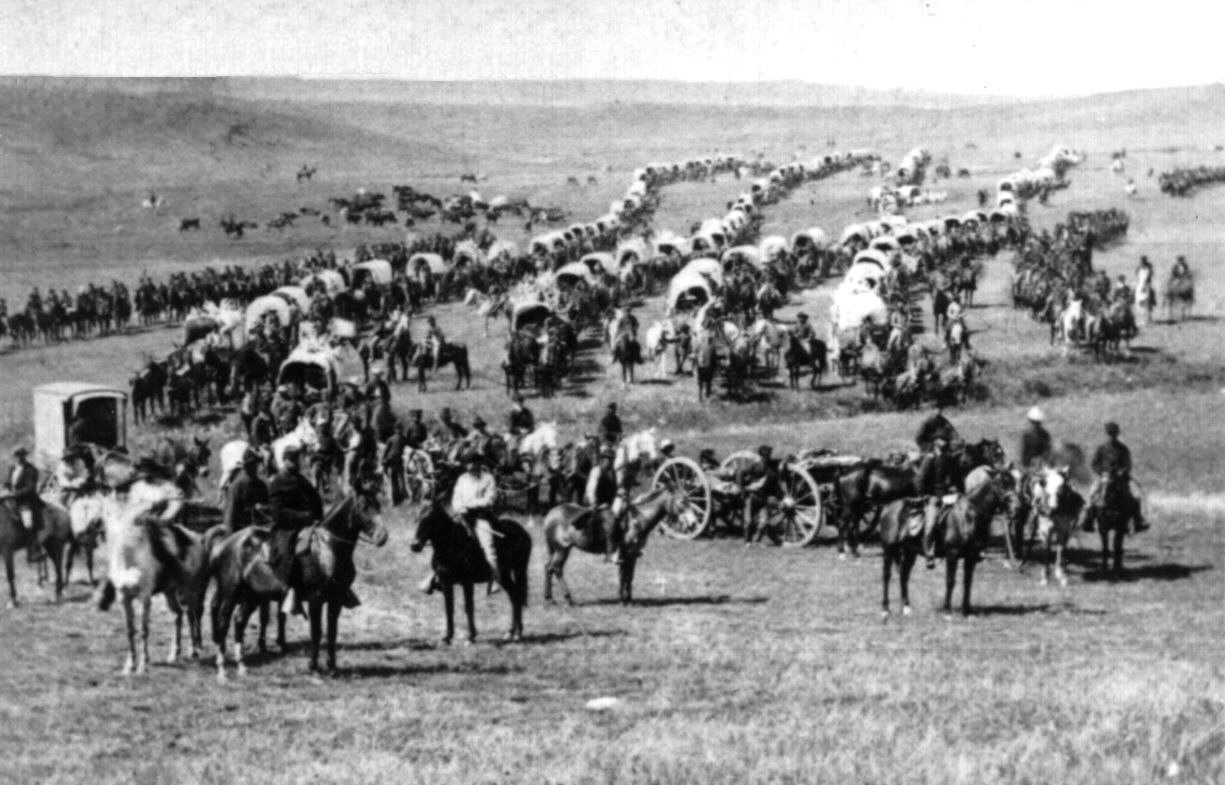

The closing of the West … and the ending of Black support in the South. There were three key developments that shaped America deeply during the remaining years of the 1800s. First, with the war over, the expansion of White America west into Indian territory resumed on a large scale. It, of course, had never ceased entirely during the war. Once again, the Indians fought back the best they could. But they were vastly outnumbered. And being hunters by occupation, the slaughter of the huge buffalo herds that once covered the West (by both rifle-carrying Indians as well as Whites) undercut deeply their economic foundations.

Custer leads a wagon-train through the Dakotas – 1874

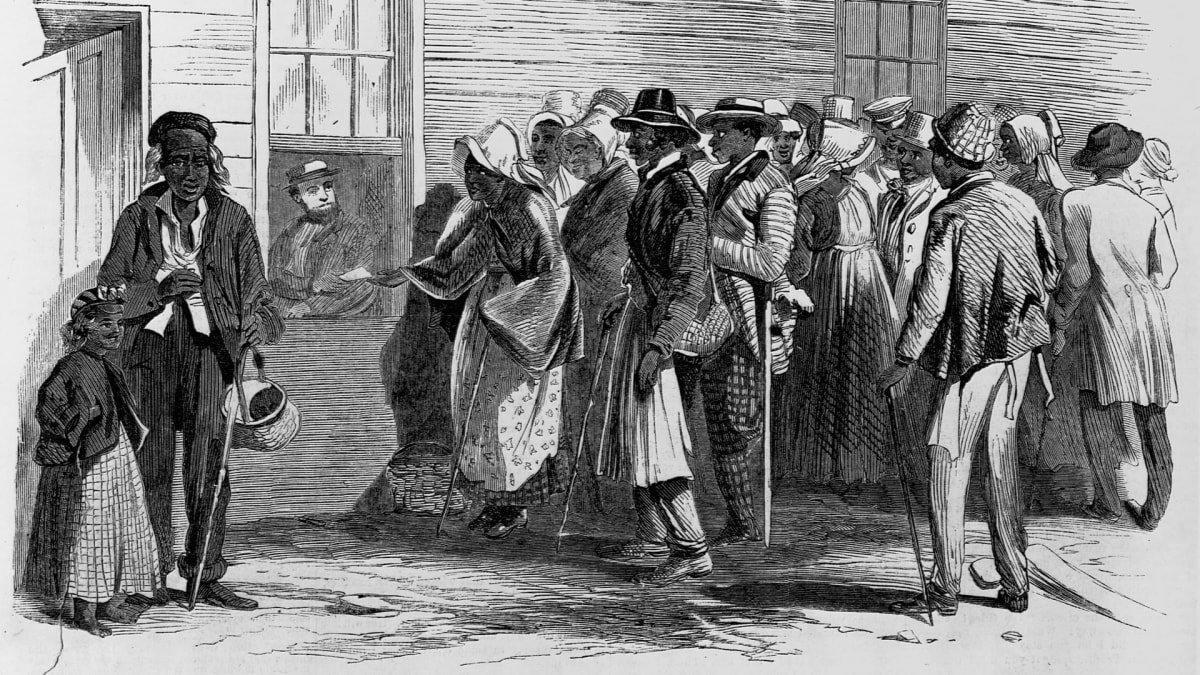

Meanwhile, for Southern Blacks, the removal to the West (to fight off the Indians) of the Federal troops sent to the South after the war to protect Black development, meant exactly that: the end of Black development in the South. Leading in the effort to keep Blacks “in their place” was the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), headed up by former Confederate officers, and widely spread across the South. Black life in the South thus became once again most difficult.

Blacks seeking rations – 1866

As for the Indians, they were forced onto reservations, usually arid lands of no interest to White intruders. And there they were expected to make of life what they could (not much). There were some tribal escapes from these reservations, episodes that did not go well for the Indians. By the end of the 1800s, the remaining Indian population had lost its ability and thus resolve to do anything about its situation. Thus in the prototype cowboys-and-Indians contests (inspiring stories that soon became entertainment as books and movies) the cowboys always won, and won most handily. For Europeans, to the extent that they even had any thoughts on America, this would be the image they would hold for the longest time of America and its “cowboy” Americans.

Geronimo at camp with some of his young warriors

Continuing industrialization, and accompanying moral problems. The second key development was the massive industrial output that the American economy produced. Much of that had started before the war. But the war merely increased greatly the production of agricultural goods, raw materials used in industrial production, industrial machinery to process such production, and the roads and railroads needed to move these goods.

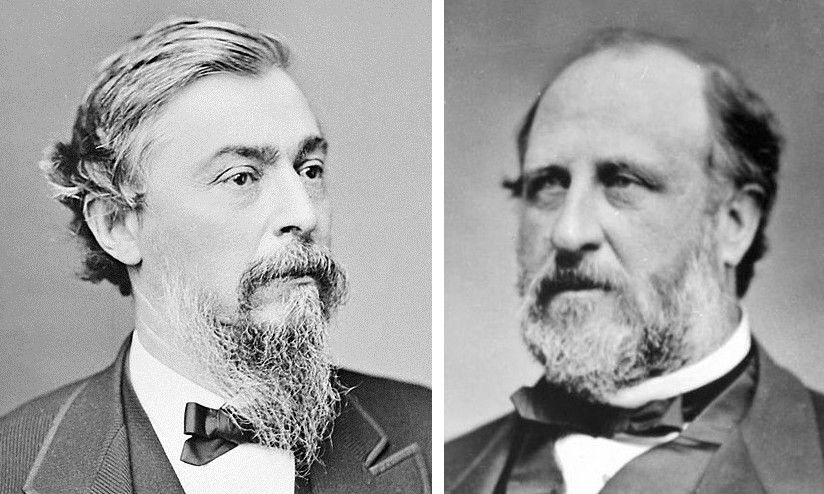

This in turn inspired deeply the world of finance, needed to support such development. Unfortunately, the world of finance operates a bit more out of sight than does the world of industrial production, and that in turn encourages behavior that is best described as motivated by mere greed, a lot of it most immoral, such as the huge scandal that broke during Grant’s presidency over Thomas Durant’s Crédit Mobilier financing of the huge railroad project linking the Midwest with the far West (1872). Then there was “Boss” William Tweed of Tammany Hall, whose corrupt behavior during the 1860s and 1870s was a regular feature of the way politics was conducted in both New York City and New York State (although the style would continue even after Tweed’s death in 1878). It all made Tweed a multi-multi-millionaire, at the cost of the New York taxpayer. But that’s just how things went, as long as there was no higher authority, no political “referee,” to keep the financial game clean. Things could get to be very corrupt, though considered cynically by many as merely standard political procedure!

Durant “Boss” Tweed

Also, the conversion of the country’s economy from one based on countless small farms and businesses across the country to now a world of fast rising “big business” would in itself change deeply the moral profile of America, especially a moral profile long resting on the moral foundations of Middle America, and its strongly Christian character.

That is because, with this rise in grand industrialization, the nation’s wealth began to accumulate into fewer and fewer hands, wealth that those who actually worked to build that wealth, the common laborer, enjoyed almost none of, and thus were having a very hard time making ends meet.

Thus by the end of the 1800s, an extremely wealthy 1 percent of the American families enjoyed 50 percent of the nation’s wealth; the next 11 percent, representing the “well-to-do,” earned about 35 percent of that wealth; the American middle class, constituting about 44 percent of the total, earned a little over 12 percent of the nation’s wealth, and the poorer working class, comprising another 44 percent of the total, earned only about 1 percent of the nation’s wealth. And even within that top 1 percent, most of that was owned by only a small number of families.*

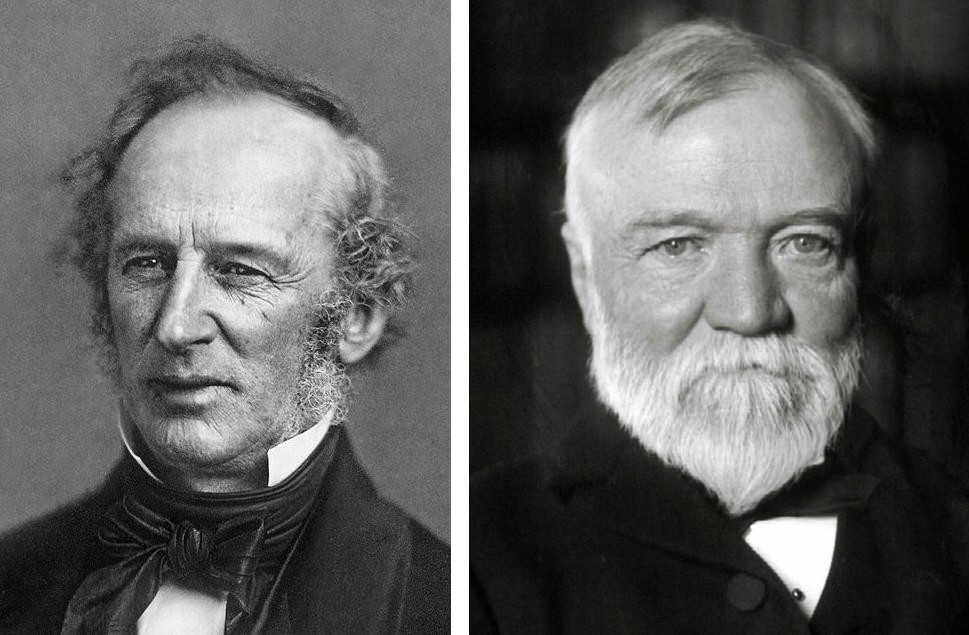

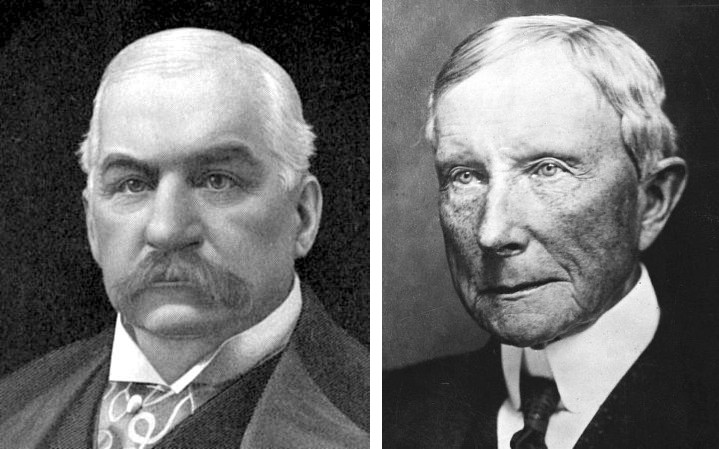

True, the financial-industrial greats did make some great contributions to American society. Such were Cornelius Vanderbilt (a steamship and railroad developer active before, during and after the Civil War), Andrew Carnegie (a Scot who came to America and was very active in building up the American steel industry during the second half of the 1800s), J.P. Morgan (New York mega-banker, who came to the rescue financially of the American government and economy in both 1893 and 1907), and John D. Rockefeller (oil industrialist during the second half of the 1800s and early 1900s, owning at one point 90% of America’s newly developing oil industry).

But the way these few individuals were able to gather in their hands the wealth of the nation had to be addressed. But that was not to happen until the early years of the 20th century, and the presidencies of Teddy Roosevelt and Howard Taft. More of that to come.

Vanderbilt Carnegie

Morgan Rockefeller

American imperialism. Thirdly, with the war over, America found itself increasingly interested in events going on outside the country. America was never a passive society, its expansive energies however previously focused “at home,” with the challenge of pushing ever-further west into Indian territory. Now that America had been largely settled, those same expansive energies could now be directed abroad. And indeed they were.

Most naturally, a rapidly growing American industrial world was just as interested in commerce abroad as were such Europeans as the English, Dutch and French, who actively pushed ever-deeper into East Asia, and further inland into the unknown continent of Africa.

Liberia. Africa proved to be an early American interest, when, in the early 1800s, the American Colonization Society helped some free Blacks “return” to Africa, to the shores of what would become the American-supported republic of Liberia, with its capital Monrovia, named in 1824 after the American president. Ultimately some 16,000 Black Americans would make the journey, and build there a society of their own, based as much as possible on their American background … finding it very difficult to integrate with the local African population already located there.

Japan. And Japan would be an early interest (even before the outbreak of the Civil War), Americans joining the Europeans in their interest in trade with the East, plus in their religious motivation to spread Christianity (thus “civilization”) abroad. Japan had been a fervently “closed” society since the arrival to power of the Shogun at the beginning of the 1600s. And Westerners now decided that it was time to “open up” Japan. American President Fillmore clearly wanted to get in on the act, and sent naval commodore Matthew Perry to Japan under instructions to get the Japanese to agree to open their ports to American trade − however Perry found it necessary to achieve such a goal. It took some showmanship (early island invasions) and a couple of visits (1853 and 1854) before Perry got the Shogun finally to agree to the opening of Japan to America (and thus also the West). And that would give the world an early illustration of how America was planning to move abroad, both diplomatically and militarily.

Japan. And Japan would be an early interest (even before the outbreak of the Civil War), Americans joining the Europeans in their interest in trade with the East, plus in their religious motivation to spread Christianity (thus “civilization”) abroad. Japan had been a fervently “closed” society since the arrival to power of the Shogun at the beginning of the 1600s. And Westerners now decided that it was time to “open up” Japan. American President Fillmore clearly wanted to get in on the act, and sent naval commodore Matthew Perry to Japan under instructions to get the Japanese to agree to open their ports to American trade − however Perry found it necessary to achieve such a goal. It took some showmanship (early island invasions) and a couple of visits (1853 and 1854) before Perry got the Shogun finally to agree to the opening of Japan to America (and thus also the West). And that would give the world an early illustration of how America was planning to move abroad, both diplomatically and militarily.

Hawaii. Hawaii proved to be another overseas area of interest to America, though largely through private religious and commercial groups rather than the U.S. government. Early in the 1800s, Christian missionaries (largely American, and of all varieties!) had come to Hawaii to bring it to “civilization,” with some of the “missionary families” who settled there discovering its great commercial potential, especially in the very lucrative sugar industry. Workers were brought in from Asia, and Hawaii began to take on a distinct international character. Then when in 1874 a huge succession dispute erupted upon the Hawaiian king’s death, American and British troops were brought in to get things settled down.

This worked for a while, until poor royal leadership led to economic problems, and popular revolt. At this point a new legislature was instituted, dominated mostly by members of the Missionary Party and other sugar plantation owners. Finally, more succession problems brought Hawaii in 1894 under the presidency of Sanford Dole, businessman and member of the Missionary Party, who asked the U.S. Congress to annex Hawaii as a U.S. territory. After much debate, it did this (barely) by vote in 1898.

This worked for a while, until poor royal leadership led to economic problems, and popular revolt. At this point a new legislature was instituted, dominated mostly by members of the Missionary Party and other sugar plantation owners. Finally, more succession problems brought Hawaii in 1894 under the presidency of Sanford Dole, businessman and member of the Missionary Party, who asked the U.S. Congress to annex Hawaii as a U.S. territory. After much debate, it did this (barely) by vote in 1898.

Cuba, the Philippines and China. Meanwhile America was finding itself under President William McKinley involved in a growing conflict with Spain developing in East Asia and simultaneously just offshore from the U.S. in Cuba. Cuba was still part of the Spanish Empire, but found itself ready to break away as an independent nation. This quickly involved America fighting Spanish troops in Cuba and also the Spanish-held Philippines, both of which Americans decided to help “liberate” from Spanish rule (1898). The Philippines would also continue to receive American “support” because it was strategic territory located along the American path to China, where America was deeply involved with its European allies in putting down the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), an event in which Chinese rebels were attempting to drive the Westerners out of China, and kill off the Chinese who had begun to take up Western ways.

And so America now found itself fully involved in the imperialist game right alongside the Europeans. And like the Europeans, it did so without apology, although some Americans were hotly opposed to the idea. Indeed, a very popular naval analyst, U.S. Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, in his widely read The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783, made it quite clear that such imperialism as America and the West were deeply involved in at the time was a very necessary part of civilized life. Imperialism was a necessity for any society, not only for self-protection, but also for true social success. So it was that imperialism got itself deeply moralized, along very Rational lines!

PROGRESSIVISM, HUMANISM, LIBERALISM, AND DEMOCRACY

Indeed, as the entire Western world entered the 20th century, it had the self-understanding that it was the most awesome society, civilization even, in all of history. Western dominance was global, its new industrial enterprises cranking out the most amazing products never seen before. And there was a presiding sense that this was just the beginning of even greater things. Indeed, within a few years, with America itself taking a bit of the lead in the matter, travel on the roads by self-driven vehicles instead of by horses, and even by flight in the air by similarly self-driven “airplanes,” was about to take place. This was totally unprecedented, and not even imaginable merely a generation earlier. Progress was now moving at an incredibly rapid pace.

And thus it was that Western society, including certainly America, believed itself to be moving forward into an even grander future.

Rising intellectualism

This sense of grand optimism as to where things were headed was found in the intellectual-spiritual realm as well as in the economic-material realm. It was easy to suppose that all of this material progress was something of a natural thing, something that unfolded naturally simply because there were people willing to undertake life’s challenges − and discover in the process the fact that there were actually formulas for grand success, simply in the willingness of venturesome people to step boldly into the future. It was supposedly a dynamic quite natural to man, if he would merely take up the challenge.

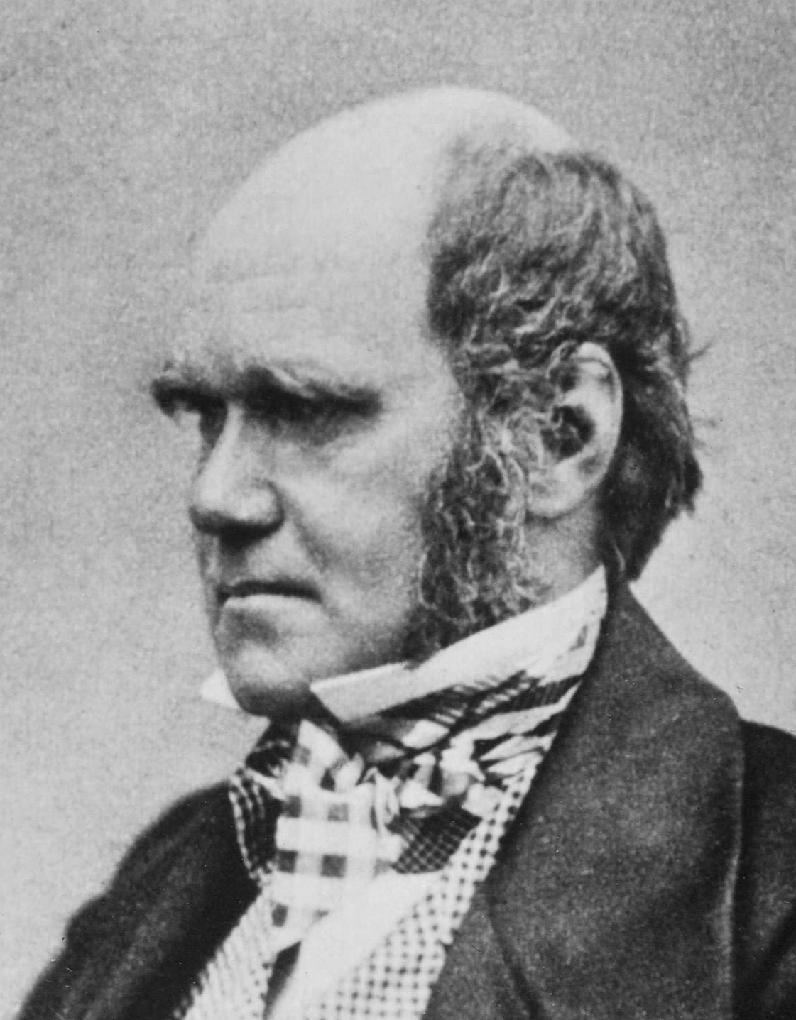

Darwinism. While America was taking the lead in the development of the unfolding material realm, Europe (especially Britain) was taking the lead in a fast-developing intellectual realm. A big contributor to this new understanding of life and its dynamics was Charles Darwin, whose research seemed to establish beyond all doubts the idea that biological progress, that is, the development of the various species inhabiting our world, was entirely a natural process of competition, one forcing newer and stronger species to emerge along life’s way.

Darwinism. While America was taking the lead in the development of the unfolding material realm, Europe (especially Britain) was taking the lead in a fast-developing intellectual realm. A big contributor to this new understanding of life and its dynamics was Charles Darwin, whose research seemed to establish beyond all doubts the idea that biological progress, that is, the development of the various species inhabiting our world, was entirely a natural process of competition, one forcing newer and stronger species to emerge along life’s way.

Such “Darwinism” was then expanded into the social realm with the understanding that all progress, but especially social progress, developed along similar lines. Progressive social development (understandably a matter of great interest to the world of intellectuals) occurred through constant confrontation with major social challenges, ones which forced players in life’s competitive game to have to come up with newer and better ways of going at life. And those better ideas and understandings were what was behind all social progress.

God did not really constitute any part of this dynamic, except perhaps to have put this game in play at the beginning of creation. Now all things, including very importantly social things or dynamics, were understood to work in accordance simply and perfectly with life’s own natural laws. And it was these very natural social laws which inquisitive intellectuals were supposedly discovering going into the 20th century, right alongside the discoveries that such people as Thomas Edison (inventor of a massive variety of mechanical instruments, from light bulbs to movie cameras) were making in the material realm.

Humanist Progressivism. Of course, such Progressivism, or Humanism, and the questions about life that these philosophies inspired (pro and con), was not a new thing. It was there in the Bible, the basic theme of the Bible in fact, recurring Humanism having been the problem constantly facing Israel of old. It was there as a question which the ancient Greek philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle attempted to answer. It was there in the Roman writings of Cicero and Seneca, and even the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. It was a matter of deep concern to the Roman-Christian Augustine. It was there across the centuries of Roman Catholic theology.

And to bring things more up to date, it was there in the thinking of Rousseau, and then to those who had to watch in horror as the French attempted through “revolution” to move to a social realm built solely on Human Reason. And now, as the Western world entered the 20th century, it was a question again, the wisdom of the past being ignored (once again) because thinkers believed that they had at that point somehow stepped well ahead of older human tendencies. They had just entered a new realm of “social science.”

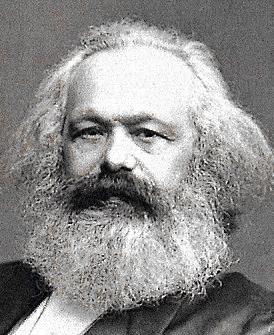

Marxism. Leading the way was the intellectual legacy produced (the 1870s principally) by Karl Marx, who once again believed that society was about to leave behind its failed social traditions and enter a new realm of “social democracy,” simply by overthrowing all those older social traditions that people had long held to. And in doing so, Marx was certain that this would allow a new spirit of human freedom to take its progressive course forward quite naturally. Marx promised that in overthrowing the capitalist-driven industrial world that was developing rapidly at the time, the common laborers supporting that industrial world would at that point naturally find themselves living freely as “comrades” in a classless, even stateless, industrial society.

Marxism. Leading the way was the intellectual legacy produced (the 1870s principally) by Karl Marx, who once again believed that society was about to leave behind its failed social traditions and enter a new realm of “social democracy,” simply by overthrowing all those older social traditions that people had long held to. And in doing so, Marx was certain that this would allow a new spirit of human freedom to take its progressive course forward quite naturally. Marx promised that in overthrowing the capitalist-driven industrial world that was developing rapidly at the time, the common laborers supporting that industrial world would at that point naturally find themselves living freely as “comrades” in a classless, even stateless, industrial society.

What an interesting dream, one that would inspire multitudes of “thinkers” to get in line with such thought. Too bad, however, that it was, like Rousseau’s work a century earlier, built on a fanciful dream that had no connection with social reality, previously, at that time, or at any time in the future.

Nonetheless, such a Humanist dream would prove to be an intellectual magnet that would never seem to fail to attract newly “enlightened” individuals, intellectuals who would inevitably come to believe that they had finally found a way to make such Idealistic social logic actually work. And over the 20th century, this line of thinking would spread widely and deeply in Western political thinking.

For instance, the huge bureaucracies, which now direct Western societies everywhere, function exactly along those same lines. Bureaucrats (the French call them “technocrats”) see themselves as being in the political business to promote an all-encompassing social progress from their offices at the society’s political center, a social progress that the common people are not yet quite able to provide for themselves. This political philosophy is called Socialism in Europe. Most ironically, it’s called Liberalism in America, even though American Liberalism operates along lines similar to European Socialism. Basically, the two are of the same mindset.*

So, such thinking was the road that many Americans were headed down as the country headed into the 20th century.

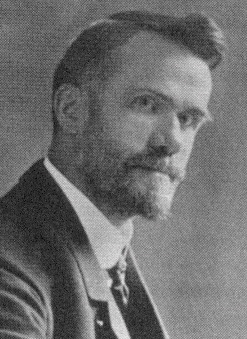

Holmes. A number of individuals stand out particularly in this matter of the newly developing worldview. One of these was the Supreme Court Justice, Oliver Wendel Holmes, who held what he called a “Realist” view, namely that the constitutional foundations underpinning the American social order needed to be creatively updated by those in a position best able to see the need for such “realistic” adjustments, not surprisingly, in Holmes’s view, the Supreme Court justices themselves. He obviously had no knowledge about how such “Realism” impacted the ancient Romans.

Holmes. A number of individuals stand out particularly in this matter of the newly developing worldview. One of these was the Supreme Court Justice, Oliver Wendel Holmes, who held what he called a “Realist” view, namely that the constitutional foundations underpinning the American social order needed to be creatively updated by those in a position best able to see the need for such “realistic” adjustments, not surprisingly, in Holmes’s view, the Supreme Court justices themselves. He obviously had no knowledge about how such “Realism” impacted the ancient Romans.

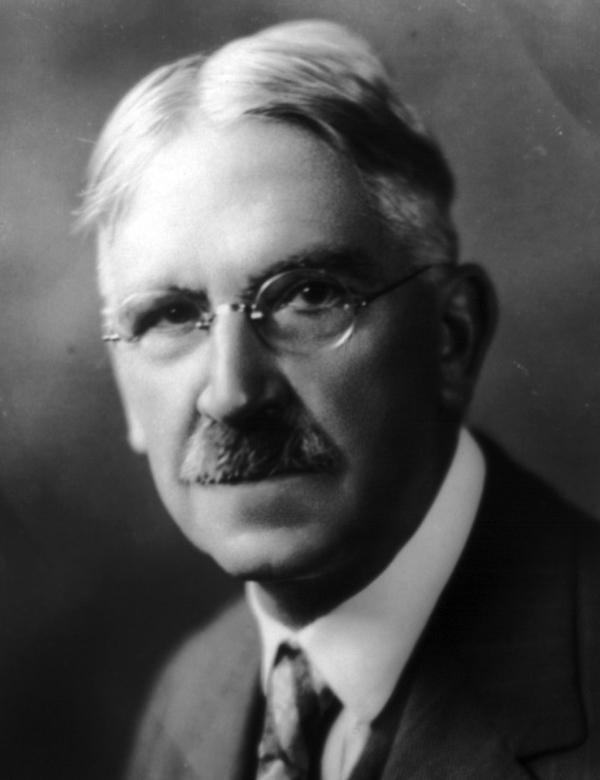

Dewey. Then there was the philosopher and university Professor John Dewey, who advocated strongly (in his 40 books and 700 articles!) in favor of a more “pragmatic” approach to child development, one that, under proper guidance, would bring forward ever-improving generations of Americans. Eventually becoming enlightened adults, such well-instructed individuals would then be better able to move “rationally” through life, rather than being directed by traditional superstitions. Like Marx, Dewey dismissed Christianity as just that, mere superstition. And he would eventually demonstrate that worldview most clearly in his contribution to the 1933 Humanist Manifesto. But more about that later.

Dewey. Then there was the philosopher and university Professor John Dewey, who advocated strongly (in his 40 books and 700 articles!) in favor of a more “pragmatic” approach to child development, one that, under proper guidance, would bring forward ever-improving generations of Americans. Eventually becoming enlightened adults, such well-instructed individuals would then be better able to move “rationally” through life, rather than being directed by traditional superstitions. Like Marx, Dewey dismissed Christianity as just that, mere superstition. And he would eventually demonstrate that worldview most clearly in his contribution to the 1933 Humanist Manifesto. But more about that later.

CHRISTIAN AMERICA RESPONDS

Once again, Christianity was thrown into confusion when it found itself challenged by this rising Humanism or Liberal Progressivism. And once again there would be those Christians who would try to “fix things” by interpreting the faith in such a way that it would not find itself in contradiction to the “scientific” mindset moving ahead in full force. In this, Europe moved even more quickly than America, though America certainly had its voices of such “Christian enlightenment.”

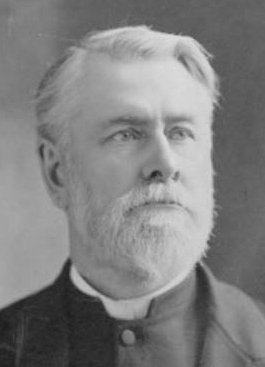

Briggs. One of those American individuals who was, in his own mind, doing nothing more than putting the Christian faith on stronger grounds, was Charles Briggs. Briggs however upset deeply the majority Christian world of his day with his announcement that Moses did not really write the five books attributed to him, because the Hebrew language used in the Biblical writings comes from a much later Hebrew version, without pointing out the fact that, true enough, such verbal narrative familiar to the ancients would be converted to written narrative only centuries later. This did not however mean that those who later wrote down that well-rehearsed narrative were simply inventing matters at that point.* He also pointed out that the Book of Isaiah was actually two different works, the second half of the book written later probably by Isaiah’s disciples.

Briggs. One of those American individuals who was, in his own mind, doing nothing more than putting the Christian faith on stronger grounds, was Charles Briggs. Briggs however upset deeply the majority Christian world of his day with his announcement that Moses did not really write the five books attributed to him, because the Hebrew language used in the Biblical writings comes from a much later Hebrew version, without pointing out the fact that, true enough, such verbal narrative familiar to the ancients would be converted to written narrative only centuries later. This did not however mean that those who later wrote down that well-rehearsed narrative were simply inventing matters at that point.* He also pointed out that the Book of Isaiah was actually two different works, the second half of the book written later probably by Isaiah’s disciples.

This was all very upsetting to those firmly in the camp of “Biblical inerrancy” (the Bible can never be considered “wrong,” on any points or matters whatsoever). But what got Briggs finally expelled from the Presbyterian denomination in 1893 was his well-voiced opinion that the Old Testament, morally speaking, was vastly inferior to the modern worldview and its accompanying moral foundations.

The Social Gospel. More “moderate” in their updating of the Christian faith were the developers of the “Social Gospel” (late 1800s and early 1900s). To them, such as the Baptist seminary professor, Walter Rauschenbusch, Christianity was not about simply finding a strong, personal faith in God, but was about finding an even higher faith through the good moral works of helping the poor and needy in the world around them. This was the way Rauschenbusch expected Christians to deal with real sin, the sins of society and its cruelties. And it was hard to argue with this viewpoint, as clearly the way wealth was being redistributed across the American social spectrum was truly alarming. And something certainly needed to be done to reverse this ugly trend.

The Social Gospel. More “moderate” in their updating of the Christian faith were the developers of the “Social Gospel” (late 1800s and early 1900s). To them, such as the Baptist seminary professor, Walter Rauschenbusch, Christianity was not about simply finding a strong, personal faith in God, but was about finding an even higher faith through the good moral works of helping the poor and needy in the world around them. This was the way Rauschenbusch expected Christians to deal with real sin, the sins of society and its cruelties. And it was hard to argue with this viewpoint, as clearly the way wealth was being redistributed across the American social spectrum was truly alarming. And something certainly needed to be done to reverse this ugly trend.

But here again, The Social Gospel merely reduced Christianity to a religion directed largely by good / logical moral reasoning rather than by some kind of mysteriously birthed personal faith. Any faith, any morality, any religion, would likely agree with the Social Gospel, with respect to its social agenda. That would include even atheistic Secularism. The Social Gospel was deeply Humanist, involving Humanism perhaps at its finest, but still nothing more than Humanism. What then was Christianity to make of all of this?

Moody. A much different approach to the question was to come from the evangelist Dwight L. Moody. Moody preached to urban crowds of “Middle Americans” who turned out to hear him. Moody avoided the grand theological debates going on in the seminaries, aligned himself with neither Christian Liberals nor Christian Inerrantists, but instead merely preached strong messages about all things being still well under God’s control, despite the social questions of the day. That certainly worked, though it did not answer the question as to where, in this age of unbounded “progressivism,” Christianity was ultimately headed (he personally hoped for the “return” of Christ to answer that question).

Moody. A much different approach to the question was to come from the evangelist Dwight L. Moody. Moody preached to urban crowds of “Middle Americans” who turned out to hear him. Moody avoided the grand theological debates going on in the seminaries, aligned himself with neither Christian Liberals nor Christian Inerrantists, but instead merely preached strong messages about all things being still well under God’s control, despite the social questions of the day. That certainly worked, though it did not answer the question as to where, in this age of unbounded “progressivism,” Christianity was ultimately headed (he personally hoped for the “return” of Christ to answer that question).

Was there then to be another Great Awakening, such as had brought America back from a similar Humanist predicament in the early 1700s and then again in the early 1800s? Would there be a similar reawakening of the Christian faith in the early 1900s?

Pentecostalism. To be sure, certain events, such as the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles (1906 to approximately 1915) would qualify, in the way it shared many of the features of the earlier Awakenings. But it was of a very limited impact in comparison to the early Awakenings, although it did inspire portions of the broader Pentecostal Movement, in particular that which in 1914 organized itself in America as the Assemblies of God. This Assemblies of God movement did amazingly well (and still does today) as a quite focused Pentecostal movement, growing not only across America but across much of the world. However, and not surprisingly, such Pentecostalism would run into a great deal of opposition by other Christian groups to its unorthodox style. But when had such revivalism not found itself opposed by “normal” Christian groups?

What then can we conclude about the state of Christianity as it moved into the early 20th century? The answer to that depends on how one views the way the Western world found itself thrown into a very deep existential crisis, the “Great War” of 1914-1918 that was soon to follow, and how it tried to get past this grand tragedy.

Go on to the next section:

The “Great War” (World War One) … and Another Recovery