CHAPTER FOUR

THE EARLY YEARS OF THE REPUBLIC

THE FIRST YEARS

Challenges to be faced

Putting the American economy on firm foundations. The American economy, originally based on the “Continental” currency but converted to the “Dollar” a few years earlier (1785) was in trouble. The troops, who had been paid in those continentals, had found them at war’s end virtually worthless in terms of being accepted for real payments for goods and services, and many had sold their continentals to speculators, generally receiving less than a tenth in real value for their face value. Something needed to be done, and done quickly, or the economy of the new Republic would fall badly.

To the task of addressing this problem, Washington appointed the ever-faithful Hamilton as his new secretary of the treasury. And Hamilton made the decision that the new government would respect the currency, new and old, on its face value, not the much lower speculative value of the currency. Suddenly a lot of speculators found themselves very rich.

As for the poor souls who had given away their earnings to speculators, they felt deeply betrayed for their years of service, and soon were ready to march against the new government.

But Washington, not liking what he knew he had to do, but being the man of valor that he was, knew he had to break up the protests, or the nation would be in deep trouble. When he then moved troops to the protest area, the latter, seeing Washington heading the troops, quickly disbanded. The Republic had been saved.

But Washington would have a political price to pay, thanks particularly to Jefferson, his secretary of state, who was growing increasingly annoyed with Hamilton, and with Washington as well, especially as Washington clearly paid more attention to Hamilton than to Jefferson.

Dealing with the bitter French-English rivalry. Jefferson had just left his greatly beloved Paris, prior to taking up his new position in Washington’s cabinet as secretary of state. To Jefferson, France could do no wrong. But in the constant tension going on between England and France, both Washington and Hamilton understood that, to the extent that America got involved in European affairs at all, despite America’s recent conflict with England, this did not change the fact that England was, strategically speaking, by far America’s best ally in dealing with the larger world.

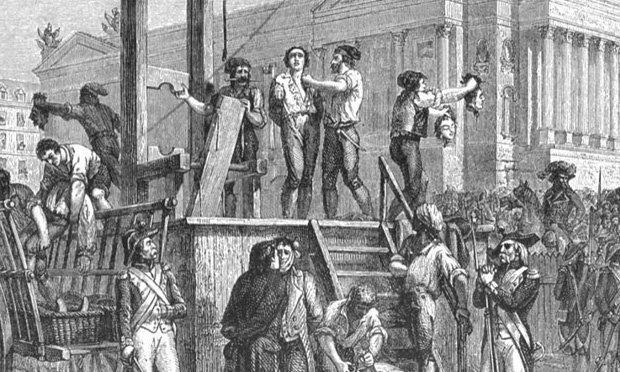

Indeed, when the French Revolution broke out the same year as the startup of the new American Republic (1789), Jefferson was adamant that America should be supporting France in this new “democratic” venture. And he would continue to be very insistent on this matter, even when clearly the French Revolution was turning into a chaotic bloodbath.

But Jefferson would not back off in his support for such “revolution” in France. For instance, in a letter written in January of 1793 to a close friend in Paris, William Short, (the “Reign of Terror” well underway at the time), Jefferson rebuked him for his criticism of what was going on in France:

My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed I would have seen half the earth desolated; were there an Adam and Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than it now is.

To Jefferson, the French cause was so lofty, so noble, that even if it was proceeding through wholesale slaughter of thousands of the French, including individuals he knew and admired personally, the French Revolution was fully justified in doing so.

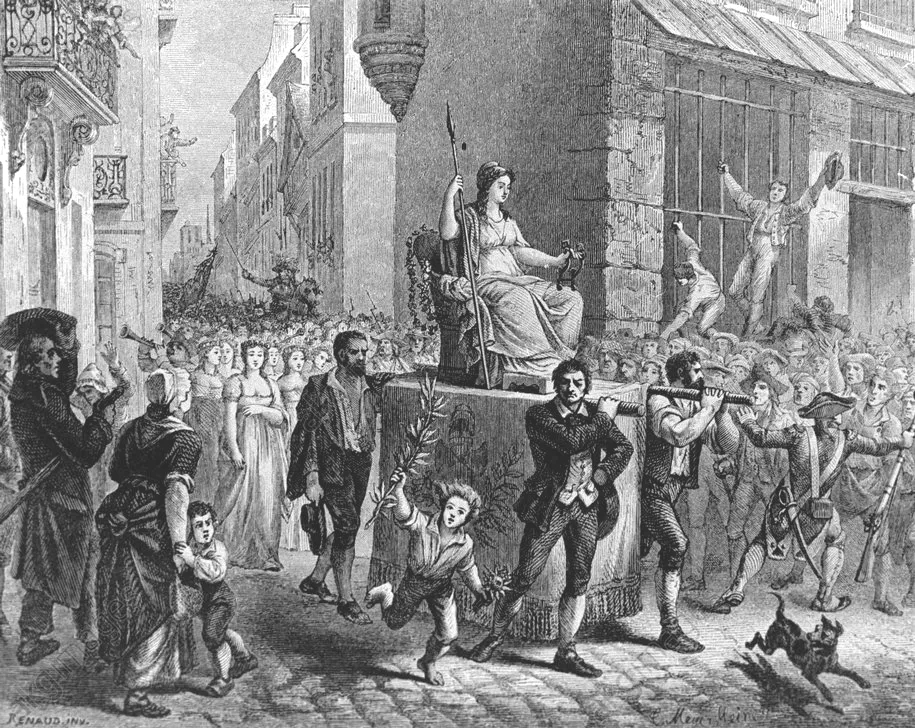

Of course there was nothing Christian, even God-like in all this. The French were supposedly operating under pure “Reason.” Indeed, the French revolutionaries were very proud of their total repudiation of all Christian tradition. At one point (November 1793), they even carried a young woman at the head of a large “Cult of Reason” parade into Paris’s Notre Dame Cathedral, to place her there on the altar as the “Goddess of Reason.” They were proud to boast that they would be worshiping Reason, not any of the traditional objects of Christian worship.

The birth of the two-party system. But it was just such “Reason” that appealed so greatly to Jefferson. And clearly, Washington and Hamilton were most unwilling to go down that road with Jefferson. Thus Jefferson resigned at the end of 1793, to take up the cause of opposing openly and deeply the “Federalist” Hamilton, and also Washington. And in doing so, Jefferson was also able to convert Madison from his earlier pro-Federalist position to now helping Jefferson in developing his anti-Federalist “Democratic-Republican” Party (actually founded the previous year).

Thus America’s two-party system was born. Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party (also termed at the time simply as the “Republican Party”) was designed to protect “states’ rights” against an expansive Federal authority (Washington and Hamilton’s in particular). Hamilton and Washington’s Federalist Party (formed in 1791), on the other hand, was designed to further unify the country as a federal union of the various states … and would go through a number of identity shifts with various rising social developments, becoming the Whig Party, the American Party, and then, just prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, the Republican Party – the Republican Party still in existence today.

Washington steps down. Washington initially agreed to serve merely the first presidential term, as he truly wanted just to enjoy life at his plantation home at Mount Vernon. But in 1792 he very reluctantly agreed to the pleadings of many to serve yet another term. But at the end of that period, he was more than happy to finally achieve his retirement. And in this, he set something of a tradition that presidents should serve no more than two terms, and also that the presidency is an office of national service, not some kind of personal power position that overactive political egos always hunger for, and hang onto for as long as possible.

The Adams presidency (1797-1801). In the country’s first election, Adams was the runner-up to Washington, and thus, according to how things at that point were expected to work, awarded by the presidential electors the position of Vice President, where he would find out how meaningless the position can be. Indeed, Washington never consulted him on any matter. But it did put Adams in the position of being potentially Washington’s heir-apparent as the country’s next president when Washington chose not to run again. However, Adams got that position only when Hamilton, who hated Jefferson more than he disliked Adams, threw his support to Adams, winning the election for Adams by merely one vote. Thus Adams would be the new president, and most ironically, his adversary Jefferson would be the new vice president.

As president, Adams found himself caught in the middle between Northern Federalists (supposedly his own support group) and Jefferson’s Southern Republicans … Jefferson’s group strongly favoring the French, and the Federalists favoring the British in the French-British war going on at the time. The Federalists, being in the majority, nearly brought the country into a war with what was at that time a very haughty Napoleonic France. But Adams negotiated peace terms with the French, saving the country from war, but thereby losing the Federalist support needed to be re-elected to presidential office. Few appreciated what it was that he had just done for the young republic.*

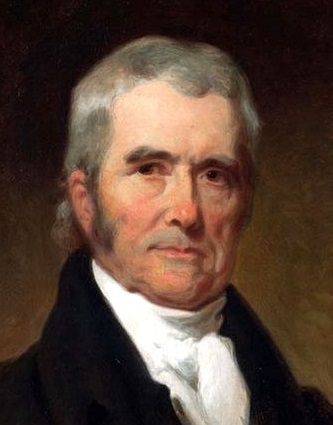

John Marshall. One thing Adams would do was to have a lasting effect on the American political system: his last-minute “midnight appointment” of Virginia aristocrat (though born in relative poverty) John Marshall as Supreme Court chief justice.* Adams probably had no idea that in choosing Marshall, he would be altering deeply the original intent and power assignments of the Constitution.

John Marshall. One thing Adams would do was to have a lasting effect on the American political system: his last-minute “midnight appointment” of Virginia aristocrat (though born in relative poverty) John Marshall as Supreme Court chief justice.* Adams probably had no idea that in choosing Marshall, he would be altering deeply the original intent and power assignments of the Constitution.

Marshall was a Federalist, and thus in favor of a strong central authority heading up the Union. But how that would impact the Federal judiciary was not anticipated by Adams (or others at the time). But in his 35 years of service, Marshall would do much, simply by judicial decree, step by step, to make not only the Federal government in Washington the supreme power in this union of various states, but the Supreme Court itself the determiner as to what the ultimate law, the constitutional law directing the federal union, was to look like and how it was to operate. This would make the Supreme Court – not Congress – to be the country’s chief legislative body, the final authority on how American law was to be shaped and enforced.

Wow! No one saw that coming at the time. But no one challenged Marshall, probably because his pronouncements helped considerably to advance the agenda of the then-dominant Federalist Party (more “unifying” power over the various states granted to Washington, D.C.). And when Jefferson and his Democrats came to power (more into “states rights”), there was nothing they could do to remove Marshall, because according to the Constitution, Marshall was empowered to hold his political position for his life, if he so chose to do so, which was indeed the case, Marshall occupying that powerful position until his death in 1835.

We will have more, much more, to say about this matter of the Supreme Court surpassing in power the people’s representatives in Congress as the nation’s supreme legislative or law-making source.

Jefferson as president (1801-1809). Jefferson became president in 1801, and would have a “mixed” success as president. He succeeded brilliantly in sending a naval fleet to end the extortion imposed on shipping in the Mediterranean by Barbary pirates operating out of the ports of North Africa. And he sent delegates to Paris to purchase from Napoleon the city of New Orleans based strategically at the exit of the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico, only to have his envoys come back to America having purchased France’s entire claim to the vast Louisiana territory to the West of the Mississippi, the money-short Napoleon eager to gain the now highly respected dollars that the Jefferson-despised Hamilton had worked so hard to make into just such a strong currency. Ironic!

But Jefferson also became the authoritarian power that he once despised in others, getting his supporters in Congress to back him in punishing the British economy for the way American neutrality in the French-British conflict was being violated by the British – by shutting down sectors of American trade with the British (the 1807 Embargo Act). Then, to be “fairer” in the matter (New England tradesmen who depended on their trade with the English, were furious), he also, in early 1808, blocked trade more broadly, thus impacting also trade with the French (mostly the South’s agricultural exports), nearly destroying the American economy in the process. Finally, two days before the end of his time in office in March of 1809, he realized the disaster that he had created and reopened American industrial trade to both parties. But the damage was done.

THE WAR OF 1812 (ACTUALLY 1812-1815)

Jefferson’s place was taken by his understudy Madison, who actually seemed to return to his older Federalist, or at least “nationalist,” ways. But that may not actually have been his choice, as he was certainly pushed in that direction by the passion that was building in America over ongoing British arrogance in seizing American sailors from their American ships, claiming these sailors to be British draft-dodgers (which mostly they were not). Americans were so enraged over the matter that in 1812 Congress (the Federalists, however, in opposition) declared war on England.

At first there were some American successes in the contest, with the British deeply focused on fighting the French rather than the Americans. But American troops foolishly burned Canada’s capital York (modern Toronto) to the ground (April 1813), so the British returned the favor, doing the same to America’s capital at Washington, D.C. the following year (August 1814).

But their next move, the British march north towards Baltimore (that September), did not go well for the British (thus the origins of America’s national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner), humbling the British.

But by this point, both sides, American and British, were growing very tired of the war. And supposedly the conflict with Napoleon and his French had ended with Napoleon’s capture and imprisonment, and thus the British found it to be no longer necessary to fill their naval ranks with resentful American “recruits.” So peace negotiations undertaken in Belgium led to a peace treaty (Christmas 1814).

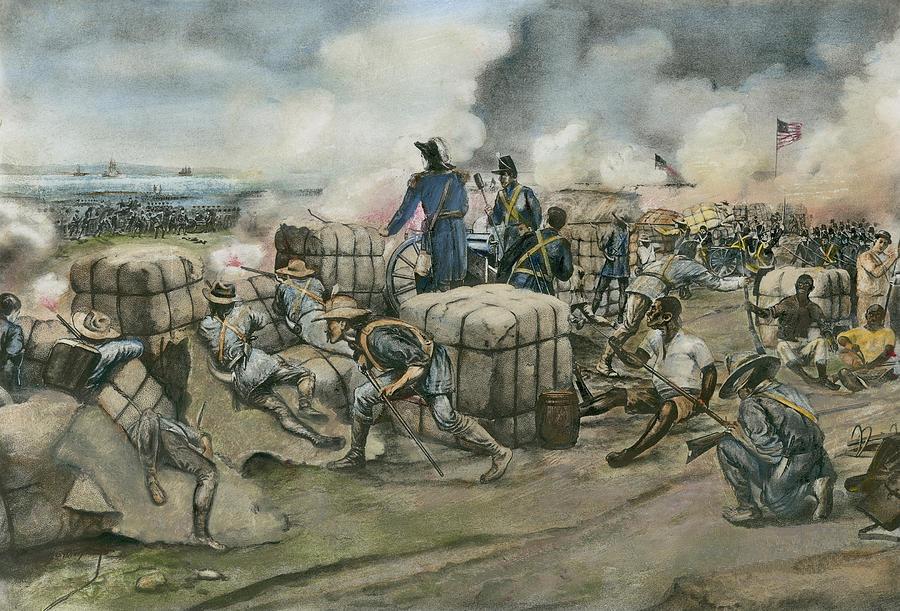

But news of the new peace did not immediately reach overseas to America, where British and American troops were gathered for a fight at New Orleans (January 8, 1815), and most amazingly (thanks to a clever American defensive wall of cotton bales) the much smaller American force, headed by Andrew Jackson, virtually slaughtered the attacking and quite massive British force. It was a major humiliation for the British, bringing some degree of respect abroad for American military power, and heroizing Jackson greatly within America.

And the Federalists, having opposed the decision to go to war with Britain, would be viewed by fired up American patriots almost as traitors, with the party fading out of existence after the war.

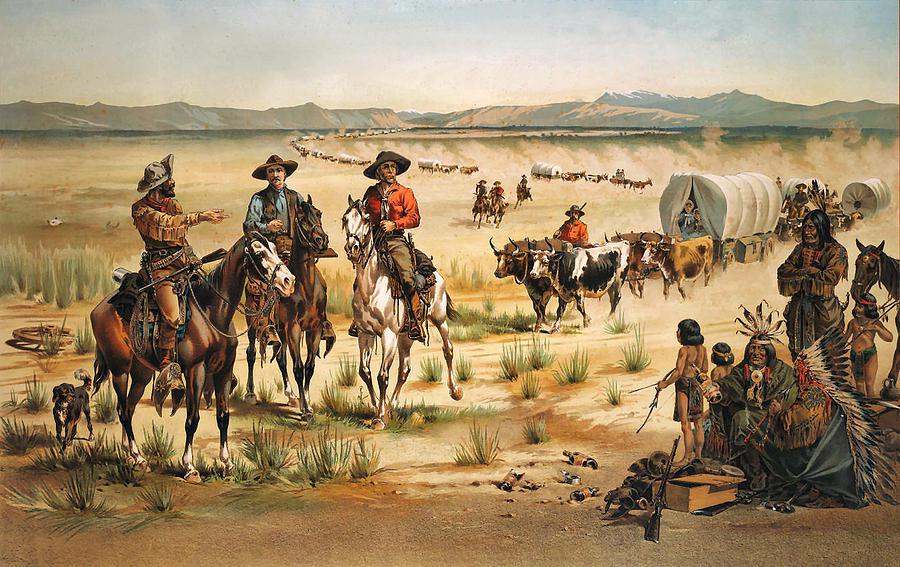

THE AMERICAN EXPANSION

Florida

War-hero Jackson was eventually called on to do something to protect Georgia and Alabama from the raids out of Spanish Florida by the fierce Seminole Indians. And in response, Jackson sent his troops into Florida (1818), not only defeating the Indians but then announcing the American takeover of Florida. The Spanish, in a very weak position at that point, were happy the following year to receive $5 million in payment from America in formalizing American ownership of Florida. Again, Jackson got greatly heroized.

Slavery, and the “Missouri Compromise” of 1820

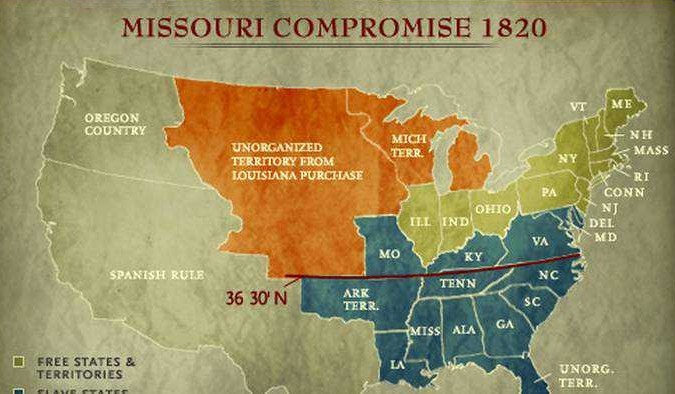

But this American expansion brought with it a huge problem, one that was to tear at the country. When Missouri applied for admission into the Union in 1819 as the 23rd state, this problem exploded. At this point America clearly had eleven “free states,” located in the American North, that had outlawed the practice of slavery, balanced in number by eleven “slave states,” located in the American South. With Missouri being a border state, part of it settled by “free” settlers, part of it settled by small-scale slave owners, it became a huge question as to whether the admission of Missouri to the Union would add to the ranks of the “slave” or the “free” states.

Actually it was not just a matter of slavery but also one of differing political mindsets, the South still idealizing a society of glorious plantations, directed by a small aristocracy presiding over the tobacco and cotton production by masses of slaves. And most weirdly, the masses of poor White Southern dirt farmers who owned no such slaves and lived nowhere close to this Southern ideal, nonetheless were themselves deeply entranced by this impossible dream.

Furthermore, the freeing of the slaves would most likely put freed slaves on a social-economic par with the poor Whites, something that the latter was most adamant about never, never happening.

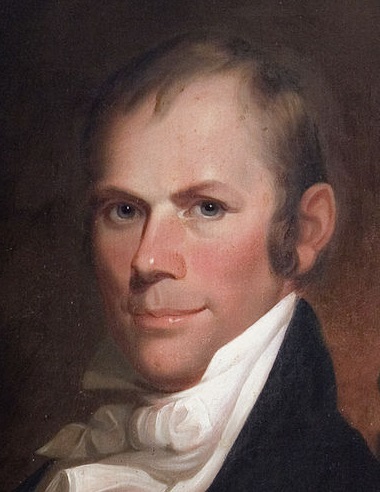

It was Henry Clay that pushed hard for Congress’s acceptance of the “Missouri Compromise.” He finally got Congress to agree to a geographical line extending West, a line which designated that lands north of that line would in the future come into the Union as free states, those below that line permitted to do so as slave states, with no further argument over the matter. And with Maine ready to enter the Union as a Northern Free State and Missouri, even though it was located north of Clay’s dividing line, deciding to enter the Union as a Slave State, thus keeping the North-South balance at 12 states each, this supposedly resolved the problem fully.

The “Missouri Compromise” supposedly had saved the Union by finally putting the matter to rest. In fact, it only made the tragic seriousness of the issue as a matter of deeply divisive principle all the clearer to everyone.

The Monroe Doctrine

Meanwhile, colonials in New Spain had taken note of Spain’s political weakness revealed in the Florida crisis. And a bitter rivalry back in Spain between Monarchists and Republicans only worsened Spain’s political image. Spanish colonials realized that this presented a golden opportunity to follow the American example, and declared their independence from their Spanish mother country … Mexico in 1821, with Central American states soon to follow.

Then when it appeared that France might also take advantage of a weakened Spain – to possibly reassert French power in the Americas – both Britain and America became quite nervous. America, of course, intended to exploit fully its holdings in the former French Louisiana and wanted no complications to arise from a renewed French interest in the Western Hemisphere. And Britain had been developing important commercial ties with Latin America and did not want to see those interests lost through French involvement, or even a return of the Spanish to their former colonies.

Thus it was that both America and Britain were to come to an agreement on the idea of defending Latin-American independence. But the British let American President James Monroe take the lead on the matter in announcing in 1823 his “Monroe Doctrine,” making it clear that America was ready to defend the rights of its Latin neighbors to their independence. But the world knew that behind this bold assertion was also the readiness of the British navy to see the doctrine enforced fully.

In any case, this began America’s move into the larger world of international diplomacy, as something of a new player of the game.

Jacksonian America (1830s)

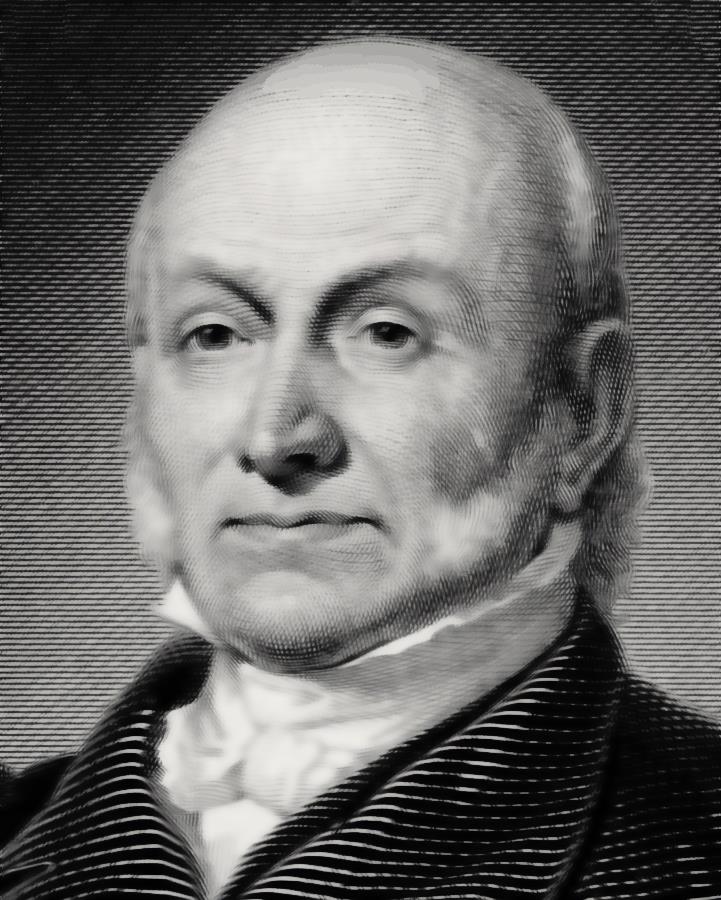

Monroe would finish out his presidency with America in quite good shape socially and economically, and be followed in the presidency (1825-1829) by John Quincy Adams, son of the former president Adams. The younger Adams’ four years as president involved a continuation of those good years.

But it was also a time of political turmoil in the nation’s capital. The Federalist Party was gone, and Jefferson and Madison’s Republican Party was itself in a state of confusion because of political rivalries inside the party, especially between the older “states’ rights” members and the younger “American nationalist” members. Much of this turmoil also had to do with the way Henry Clay threw his support to Adams in the 1824 contest between Adams and Jackson, infuriating Jackson. Jackson would not merely sit out the next four years in anger, but would found the Democratic Party, whose sole purpose was to get Jackson elected in the 1828 elections. And in this, it succeeded masterfully. The quiet Adams was easily pushed aside by the charismatic “champion of the people” Jackson, supposedly indicating the move away from government by an aristocratic ruling class to now rule by true democracy.

A Frenchman who came to America in 1831 to check out this matter was Alexis de Tocqueville, who published his observations in his two-volume Democracy in America (1835/1840). He noted the strong individuality of the typical American, the readiness to take up any new challenge (often without completing an older challenge!), and the spirit of basic equality of all (the Whites anyway) in American society. And he well-understood the origins of this mindset in the Puritan moral-legal foundations set out generations earlier, foundations contained in their colonial covenants and subsequent state constitutions.

But he also noted the rising tensions over the issue of slavery, a moral idea in such deep conflict with the democratic instincts of most Americans, that he actually predicted that a very ugly war was most likely to develop in America over this matter.

The Indian Removal or “Trail of Tears” (1830s)

Something else that was unfolding at this time was a hugely tragic event, tragic for the people who had long lived in North America prior to the coming of the English settlers. White settlers coming to Georgia had long looked to the lands occupied by various Indian tribes, but particularly by the Cherokee, who actually had undertaken the process of trying to conform to White ways themselves, possibly hoping to become an integral part of the Anglo-Christian world. That was not what the settlers wanted to see happen, nor did their governor, who decided that it was time to move on the matter. He got some compliant Indian chiefs to sign an agreement to move their tribes West, supposedly voluntarily, to the Indian Territory of Oklahoma.

But President Jackson at this point wanted this to be a federal, not a state matter, and took the initiative to have Congress pass the Indian Removal Act of 1830, a much broader Indian removal program. But an appeal by the Cherokee to the Supreme Court to block this act led Marshall to pronounce in favor of the Cherokee (1831). This in turn led Jackson to inform Marshall that the Supreme Court had no way of enforcing its decision. The Indian removal would proceed as planned.

Imagine a US president ignoring a decision handed down by the Supreme Court! This was just power versus power!

The Indians, of course, resisted as best they could. In Illinois the Sauk and Fox Indians, led by Chief Black Hawk, revolted against the order and had to be put down violently by the Illinois militia (including in its ranks Captain Abraham Lincoln). But one by one, the Choctaw (1831), Seminole (1832), Creek (1834), and Chickasaw (1837) were forced to move.

The worst removal occurred among some thirteen thousand Cherokee, who in 1838 were first herded into camps in Tennessee and then force-marched westward through a freezing, snowy winter by Gen. Scott’s soldiers. Cold, disease, and starvation took a huge toll in their numbers. Thus many died along this “Trail of Tears,” possibly as many as a third of all Indians involved.

In all, some 46 thousand Indians were relocated in order to open the way for Anglo-American settlement in their traditional lands.

Texas Independence and the Mexican-American War

The Mexican territory of “Tejas,” to the north of the Mexican heartland, had been only lightly settled by the Spanish, the area well defended by the fierce Comanche Indians. In the early years of Mexican independence (the 1820s), the Mexican government thus made it a policy of inviting Europeans (Americans responding eagerly) to settle the area, in the hopes of bringing the region to “civilized” status. But when the American flow to the region became a flood, the Mexicans tried to put a halt to this dynamic (1830), merely driving the American settlers to resist (1832), and then fiercely fight off Mexican troops sent to enforce the ruling (1835).

War resulted, the Texans declared independence (March 1836), and a huge Mexican army immediately marched north, committing atrocities at the Alamo and at Goliad, which merely steeled the hearts of the Texans.

Most surprisingly (to the outside world), Santa Anna’s Mexican army was then rather quickly defeated the next month at the Battle of San Jacinto. Thus Texas at that point found itself indeed quite independent.

The question then arose, was Texas to be a sovereign state, or a new member of the United States? The matter did not have an obvious answer, even on the U.S. side of the issue. Slaveowners (migrating into Texas from the American South) were numerous in Texas, thus making Texas’s entry into the Union something designed to heighten the growing American tensions over the slavery matter.

Anyway, the matter was repeatedly put off, for almost ten years, before out

But this merely drew Washington into ongoing Texas border issues, and Polk got Congress to go to war with Mexico over the matter (1846). For Mexico, the war did not go well, and Mexico now lost even more Western territory in the process (New Mexico, Arizona, California, and parts of Colorado and Nevada). Thankfully, Congress was wise enough to compensate Mexico financially ($15 million) for the loss, wise because this sealed the matter, and kept it from coming back into play at a time in the near future when America would be distracted deeply with its own civil war.

The Oregon Territory

The British and Americans had been able to agree on a Canadian-American border extending westward along the 49th parallel from Minnesota to the Rocky Mountains. But the territory to the west of those mountains was disputed by both Americans and British. The British claimed the Oregon Territory, and the Americans, already moving in huge numbers into the territory via the “Oregon Trail,” claimed the land bordering the Pacific, all the way north to the border of the Russian territory of Alaska at the 54°40′ latitude.

The feelings in America grew increasingly heated over this, with some calling for “Fifty-Four Forty or Fight.” Finally, in 1846 the British and Americans came to an agreement to simply extend the 49th parallel border all the way west to the Pacific (but swinging just south below Vancouver Island). And thus the Oregon Territory came officially into American hands.

ANOTHER SPIRITUAL WANDERING

Materially speaking, America was doing awesomely well. Moving goods from field to factory, and Americans always on the go (usually westward), was greatly facilitated by the development of rail and canal transport, those two technologies requiring the development of massive infrastructure (the laying of tracks and the digging of canals), not to mention the steam power that drove the trains and boats (and factory machinery). Indeed, by the early 1840s there were some 1,200 cotton mills in operation (mostly in the Northeast), the Erie Canal was in place, with the Baltimore railroad linked to it, the McCormick reaper was harvesting huge wheat harvests, steam boats were making regular runs on the Great Lakes, etc. America at this point was an industrial giant (not yet quite acknowledged by the European powers). And it all seemed so natural to America itself.

An “Enlightened” America

Also, for a number of Americans, located especially in the American East, a comfortable small-town life, dependent on an economy other than just agriculture, seemed to have a natural peace and prosperity to it. Not surprisingly, life there took on a more “rational” character, thus stepping America back from its previous fervency in its Christian spirituality. A number of Americans, especially among the more leisured professional classes, found themselves less interested in what God might do in their lives and more interested in what they might achieve for themselves under this more rational social realm clearly emerging around them.

These Americans did not abandon Christianity, because being Christian was understood to be the same as being “civilized.” But the faith component (trust in God as the essential higher power in their lives) was disappearing. Its place was being taken by a rational morality, a key part of Enlightenment Humanism that was sweeping intellectual circles at the time, in America as well as in Europe. Such Humanism usually claimed the moral teachings of Scripture, especially the teachings of Jesus, as its “Christian” foundation. But in the end, no such connection was absolutely necessary, for these were supposedly “self-evident” truths that any rational person would understand as the foundation of any life lived properly.

Indeed, there were even “very enlightened” Americans who were totally disdainful of people who still held “pre-scientific” superstitions about life, people who were intellectually unable to shake off the “silly old Biblical beliefs” about people walking on water and raising the dead back to life.

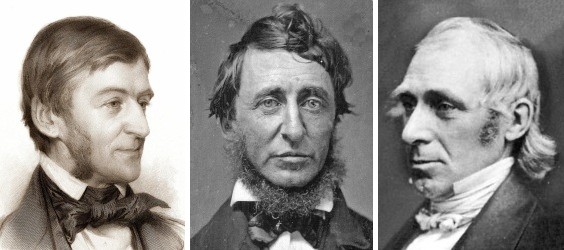

The Transcendentalists

A perfect example of this new enlightenment were the Transcendentalists, who undertook the quest for “God,” but not through the way of Christ. Rather, they did so as a higher order of “pure thought.” They sought, through mental discipline, to be broad in their intellectual reach, encompassing a variety of refined efforts to embrace God both in a oneness with nature and a sense of reaching beyond even the natural. They sought to be as fully “human” as possible, so as to find God as fully as possible. They too tended toward lofty communalism in the hope of reaching beyond the coarse nature of selfishness and sin, to find a more perfect human harmony.

Quite notable among this class of Transcendentalists were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Amos Bronson Alcott (father of the highly popular novelist Louisa May Alcott), neighbors in Concord Massachusetts who helped to set the pace of such Transcendentalism. Thoreau attempted to find serenity in two years (1845-1847) of relative isolation in the woods at Walden Pond, Alcott in his experimental school in Concord, and Emerson in his many philosophical lectures and writings.

The earthier intelligentsia

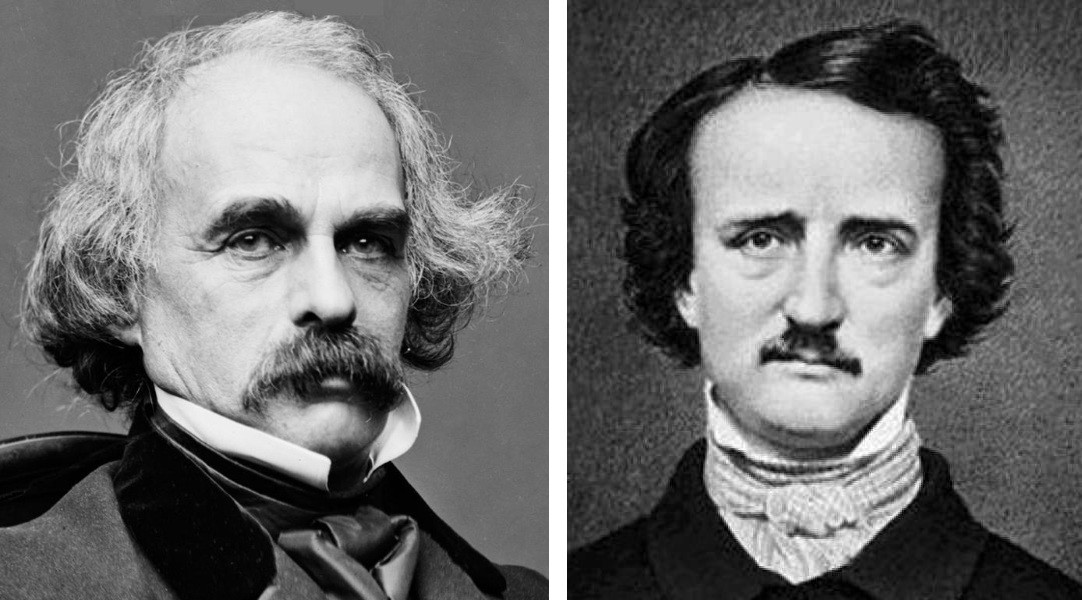

But for those less comfortable, where life’s dangers were not guaranteed to be manageable, where life could suddenly take a violent turn (hunger, disease, Indian massacre), such humanist rationality seemed as absurd to hardened “Realists” as their personal trust in a God of miracles seemed absurd to the Humanists. Indeed, even Nathaniel Hawthorne, who once was a neighbor of the Concord Transcendentalists, eventually became something of an Anti-Transcendentalist, tending to delve more into the darkness of the religious-ethical issues of his era in his novels The Scarlet Letter (1850) and The House of the Seven Gables (1851). Likewise, Edgar Allan Poe could be just as abrasive in his dislike of the romantic optimism of Transcendentalism.

Hawthorne Poe

The “Second Great Awakening”

Thankfully, God knew that his Covenant-America was about to undergo another time of major testing – over the horrible issue of slavery – and sent his Spirit anew during these times to bring America out of these wandering “Rational” ways, and back into full faith in his direction and protection. He well knew that America would need exactly that full faith, and thus commitment to the cause, in order not to fall apart in the face of the irrational horror produced by that conflict.

This Awakening was quite unique in the way it birthed the development of a massive number of non-seminary-trained lay-preachers, individuals who took up Christian ministry simply on the basis of a sense of personal call to the task. Particularly numerous were the Baptist preachers and Methodist circuit riders, the latter who covered the vast Western backlands, where settlers were widely scattered, roads non-existent, food and drink lacking, and Indians often most unfriendly.

This Awakening was also unique in the way it duplicated the role of the evangelists of the first Christian century, moving not just by programmatic interest in seeing the Christian faith extended to new territory, but simply moving in response to the promptings of what they recognized as the hand of God itself. Thus, to the shock of some of those “more reasonable” Easterners, these Western circuit riders not only preached Christ’s salvation and God’s fatherly love, they demonstrated the active power of the Holy Spirit through the amazing number of healings and other miracles that accompanied their ministry.

Setting the example for this trend was the Methodist Bishop Francis Asbury, a preacher who himself in his years of ministry (1784-1816) covered approximately 275,000 miles of travel in delivering a possible total of 16,000 sermons, and helped lead the expansion of the Methodist community during that same period from 1,200 to 214,000 members, and bring in 700 preachers to pastor this same community. That was a huge early start to the Second Great Awakening.

Setting the example for this trend was the Methodist Bishop Francis Asbury, a preacher who himself in his years of ministry (1784-1816) covered approximately 275,000 miles of travel in delivering a possible total of 16,000 sermons, and helped lead the expansion of the Methodist community during that same period from 1,200 to 214,000 members, and bring in 700 preachers to pastor this same community. That was a huge early start to the Second Great Awakening.

Quickly the Methodists and Baptists grew to be the most numerous Christian groups in America. For example, by 1840, something of the “height” of this Second Awakening, some 3,500 circuit riders and nearly 6,000 pastors were supporting the faith of 750,000 Methodists.

Some of the Presbyterians also saw the challenge and took up a similar path, creating a deep division within the denomination between the New Lights (supporting the revivalist trend) and the Old Lights (disdainful of the emotionalism of this trend). Prominent among the Presbyterian revivalists was Charles Grandison Finney, who in New York during the mid-1820s to mid-1830s developed a distinct revival style at his camp meetings, a style that others would pattern their own revivals after. These involved a huge open-air gathering of people over a period of several days (sometimes even a full week), involving preaching, singing and dancing, even shouting and fainting as signs of being possessed by the Holy Spirit, everybody having a great time!

Some of the Presbyterians also saw the challenge and took up a similar path, creating a deep division within the denomination between the New Lights (supporting the revivalist trend) and the Old Lights (disdainful of the emotionalism of this trend). Prominent among the Presbyterian revivalists was Charles Grandison Finney, who in New York during the mid-1820s to mid-1830s developed a distinct revival style at his camp meetings, a style that others would pattern their own revivals after. These involved a huge open-air gathering of people over a period of several days (sometimes even a full week), involving preaching, singing and dancing, even shouting and fainting as signs of being possessed by the Holy Spirit, everybody having a great time!

This spiritual impulse would include Black freemen, particularly in Philadelphia and New York City. Congregations known as the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Philadelphia and AME Zion Church in New York City were founded at this time (the early 1800s).

The most intense concentration of such evangelical activity was what was termed the “burned out district” by Finney, referring to an area in upstate New York where he had been very active, as revival swept back and forth across the region.

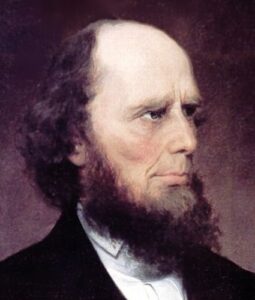

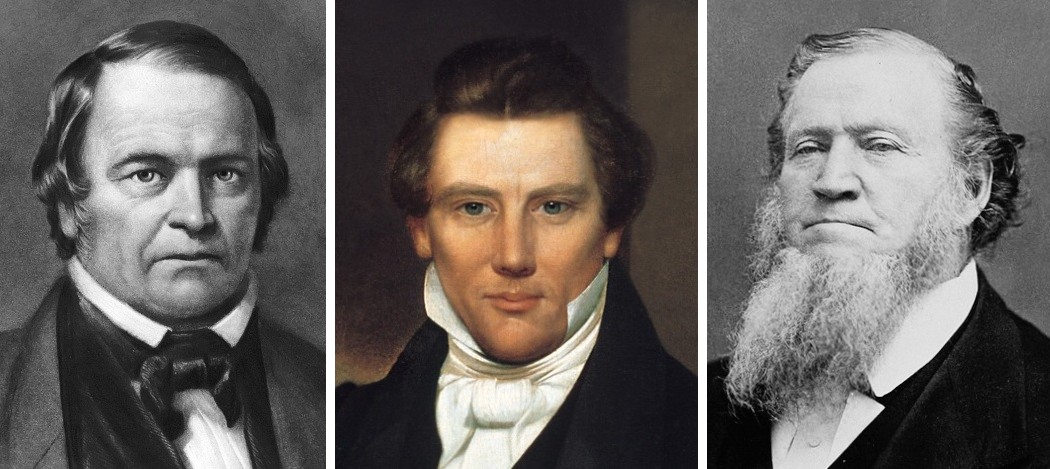

Most interestingly, it was in this same “burned out district” that William Miller founded the Seventh-Day Adventists in the 1830s, expecting Jesus’s “Second Coming” to take place soon (1843 or 1844). It was there also that Joseph Smith founded the Church of Christ of the Latter-day Saints (the Mormons) in the 1830s. Both groups would grow, despite Jesus’s failure to show up on schedule and despite the opposition of “traditional” Christians to both groups, but especially to the Mormons, whom Smith would lead in the late 1830s by the thousands (8,000?) to the American Midwest. Tragically, he would be killed there in 1844 by angry “Christians.” Brigham Young would then direct the Mormon cause, Young taking his 35 wives and hundreds of followers all the way to Utah in 1847, to build the new “Zion” and its temple at Salt Lake City.

Miller Smith Young

But the Awakening also hit more traditional Christian groups, to develop new Christian programs in a variety of ways: the American Bible Society, to make Bibles available to every American family, the Sunday School Union to teach Bible stories and teachings to rising generations, and numerous missionary societies to take the gospel to America’s various Indian tribes, but also abroad, to Hawaii, China, India, the Middle East, and then finally Africa.

Christian colleges also came to be planted in vast numbers during those years, most American colleges indeed having strong Christian roots. In fact, over 500 American colleges founded in the period since the beginning of the colonies up to the mid-1800s were founded as Christian colleges. Higher education was always considered by Puritan America, and a broader Christian America after that, as critically important to the spiritual-moral development of America, even though most of them would eventually, over the years (especially since the mid-1960s), wander far from their own founding Christian principles.

Irish-Catholic immigration

Impacting American culture greatly would also be the huge entry in the mid-1800s of Irish to America, at first largely due to the potato famine that hit Ireland in 1845, which within five years killed a million Irish, and sent a half-million to America.* These were primarily farmers by trade. But most simply ended up settling into the Eastern seaboard cities (notably New York and Boston) upon their arrival. There they took up work in the factories, or moved further West working in the mines or on the railroads, but always in the lowest-paying positions.

The Irish responded in kind, but in particular against Blacks who shared much of the same discrimination. But what would really send the Irish into a rage, would occur during the Civil War, when in 1863, the Irish found that in applying for citizenship they had been signed up for the military draft, at a time when the war seemed not to be going well for the North, and many Americans were finding ways to avoid military conscription. Riots in several cities, but especially in New York, led to the death of 100 people at the hands of angry Irish mobs, many victims simply by-standing Blacks (who because of their race were not being drafted).

Eventually the Irish would settle in and get deeply involved in the political process, even (as we shall see) constituting the heart of the New York City Tammany Hall political machine, as well as a growing part of Boston politics.

Go on to the next section:

Civil War … and Recovery