CHAPTER THREE

INDEPENDENCE … AND THE NEW REPUBLIC

“REVOLUTION”

Revolutionary “change.” This brings us to a matter of terminology. The period of history we now find ourselves entering (the later 1700s) is often termed a period of “revolution,” and thus the American war or battle that resulted during this period is often termed the “Revolutionary War.” That implied that something “revolutionary” happened to America during those crucial years of the second half of the 1770s and the early 1780s.

Certainly, the idea of a people rising up against their royal leadership could be considered quite “revolutionary,” especially in that they actually succeeded in this endeavor. But “revolutionary” also means change, deep change. But in fact, very little changed, in the sense that what America was as a society before the war, was also what it was after the war. All that Americans were doing in this war was fighting to keep the English king from taking away everything that America had become. They were simply fighting to defend what they already were, and wanted to keep it that way.

True, they would have to be inventive in order to protect that original social integrity. But they did not need to change America itself in order to succeed.

The French Revolution (1789-1800). Now let’s compare the American event to an event that was soon to follow the American event, and was itself deeply impacted by that American event: the French Revolution, which broke out in 1789, just as the various American states were uniting under their new Constitution as the “United States of America.” What happened in France was truly “revolutionary … in the worst sense of the word.

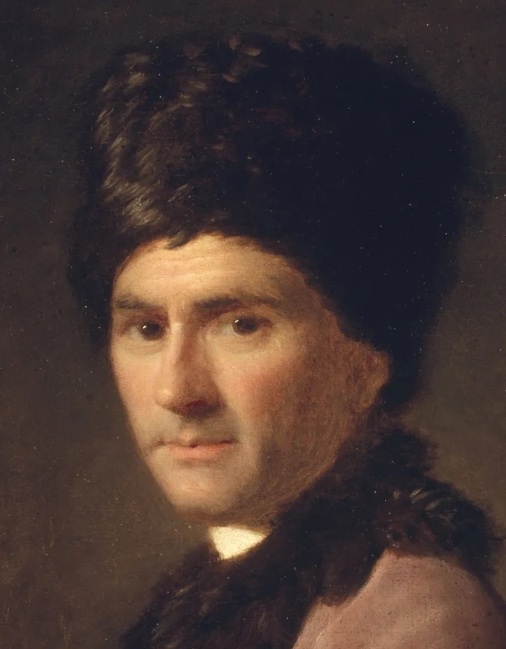

Earlier in the 1700s, philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, with his Social Contract (1762), had stirred some very unrealistic thinking, promoting pretty much the Rationalist idea so widespread among European (and many American) intellectuals that somehow social wisdom was simply instinctive to man, and that all one needed to bring that wisdom forward was to get older systems of authority off their backs and let them self-govern. Instinctive human self-interest would be more than sufficient to bring things to social greatness.

Earlier in the 1700s, philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, with his Social Contract (1762), had stirred some very unrealistic thinking, promoting pretty much the Rationalist idea so widespread among European (and many American) intellectuals that somehow social wisdom was simply instinctive to man, and that all one needed to bring that wisdom forward was to get older systems of authority off their backs and let them self-govern. Instinctive human self-interest would be more than sufficient to bring things to social greatness.

By the late 1780s, soon after the American “commoners” had won their War of Independence, French political reformers thought they were headed down the same road as the Americans, whom they had so recently joined and fought alongside in the American effort to fend off the royal absolutism of English King George III. These French reformers supposed that they therefore could automatically do the same, find political “freedom” simply by refusing to submit to royal authority. But unlike the Americans, they had absolutely no idea of whose authority they were then to operate under.

Somehow, in great part thanks to the popularity of Rousseau’s thinking, the idea that social wisdom has to be learned, experienced, and carefully developed, got left out of the picture, creating the illusion (that all Rationalists love) that instinctive Human Reason was all that was needed to build and develop a new utopian society. The French were about to find out how wrong such Rationalism would prove to be.

The reality of it all was that unlike in America, where self-government had been the practice since the English arrival to American shores in the early 1600s, self-government had never existed in France. France, like all of feudal Europe at the time, was tightly controlled by its king and the king’s small supporting group of privileged nobility. Everyone else was simply a “subject” to such authority.

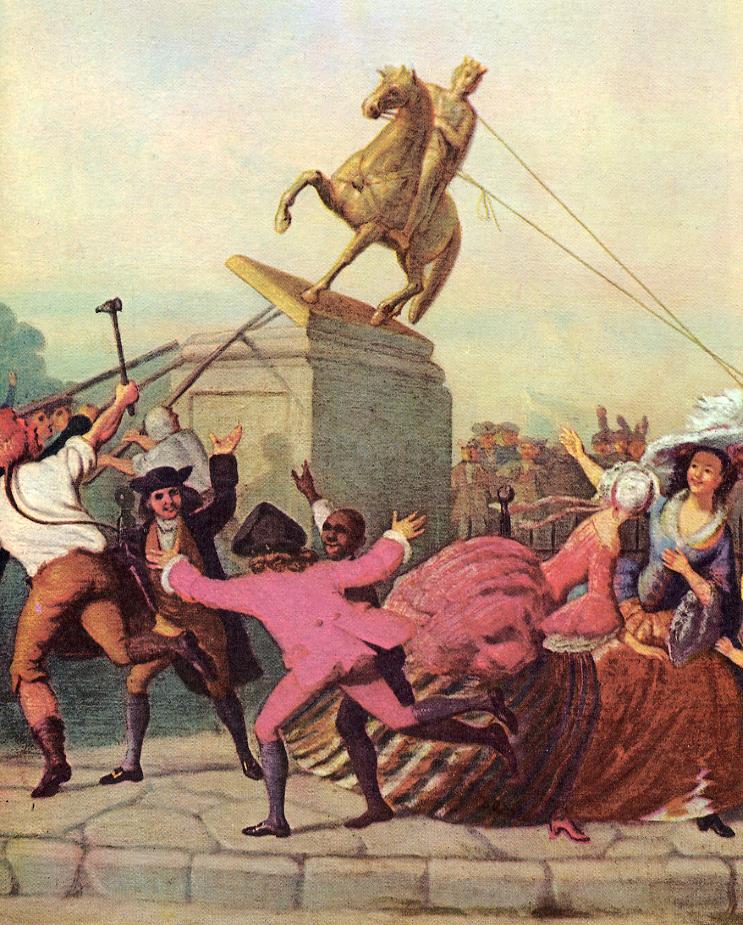

And thus it was that the French had no experience, no well-cultivated talent for the kind of self-responsibility that governed America. Consequently, with the taking up of “revolution” in 1789 involving the overthrow of the French monarchy, France simply fell apart.

That was because the “reasoning” of two groups, the more moderate Girondins and the more radical Jacobins, could not find an agreed-on strategy as to how to put this new Republic together. And after killing off the monarchy, the aristocracy, the priesthood, and even notable members of the French middle class, the Jacobins turned murderously on the Girondins.

But the sheer ugliness of a 1793-1794 “Reign of Terror” alienated deeply most of the surviving French, so that things ultimately turned brutally against the Jacobins. Thus in the end, nothing except social confusion and spiritual exhaustion was achieved by all of this “revolution.”

Eventually, step by step, military hero Napoleon took control of France (by late 1799), and then redirected France’s focus abroad, personally leading an army of fired up French commoners to assault militarily the societies surrounding France, all the way even to Moscow in Russia (1812).

So it was that the French republic ended up being an Empire (literally a military-governed society), the French back under the rule of a single individual. But they understood that. As far as the Republic went, they were clueless as to how that was supposed to work.

AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE

Background to the American event. We return to our narrative, as things stood politically in America in the 1700s. In 1714, a new British monarch, George I, a distant German cousin of the Stuart family, was called on to reign in England (he was also prince of Hanover in Germany), when the Stuart line ran out, at least as far as Protestant Stuarts went. But being weak in his command of the English language, George really depended on his British cabinet members to run things in England. And anyway, George was actually much more interested in the dynamics of the many dynastic rivalries taking place on the European continent than in the domestic matters of a fairly peaceful offshore England.

And when he died (1727) his place was taken by his equally German son, who continued to run things pretty much along the same lines as had his father.

But when George II finally died in 1760, his place was taken by his grandson, George III, who was definitely an Englishman first and foremost, and deeply interested in keeping a tight hand on political developments in Great Britain, as well as on England’s colonial holdings in America. For the Americans, who were well used to taking care of their political affairs themselves, this would come as a huge shock.

Politically speaking, the American colonials were not at all a passive people, and had participated directly in the dynastic wars that rattled Europe during the 1700s (and drove the monarchs to near bankruptcy in the process), at least to the extent that those wars spilled over into North America. The Americans conducted their own “English” battles taking place there, at their own expense, thus coming up against primarily the French (and their Indian allies), though occasionally also the Spanish. These American “colonials” fought and died for the English cause, largely at their own initiative, rather than as a matter of mere obedience to English commanders.

But this self-sufficiency of these American colonials seemed to concern the young King George III deeply, for he feared that this might set a precedent in England itself, something that he was determined was never to happen. These Americans were, after all, his subjects, just like the millions of commoners in England itself. And he expected his American subjects to act accordingly. After all, he was their sovereign king.

And certainly the Americans tried to work with this new development. But it all seemed to be so unnecessary in the eyes of many of these colonials, well used to self-rule.

Little by little, tensions rose over this matter of political sovereignty, as it slowly became a matter of great principle to both sides in this mounting standoff.

Particularly worrisome to George were the citizens of New England, and in particular those based in Boston, something of a major political center in colonial America. But that same sense of independence could be felt all the way south to Philadelphia.

The South was not quite as problematic, as the Southern aristocracy understood the game of sovereignty-from-above, as their own world there in America worked pretty much this same way.

But this could not be said to be the case of the Southern backwoodsmen, who could be just as independent-minded as the colonials in New England and the Middle Colonies.

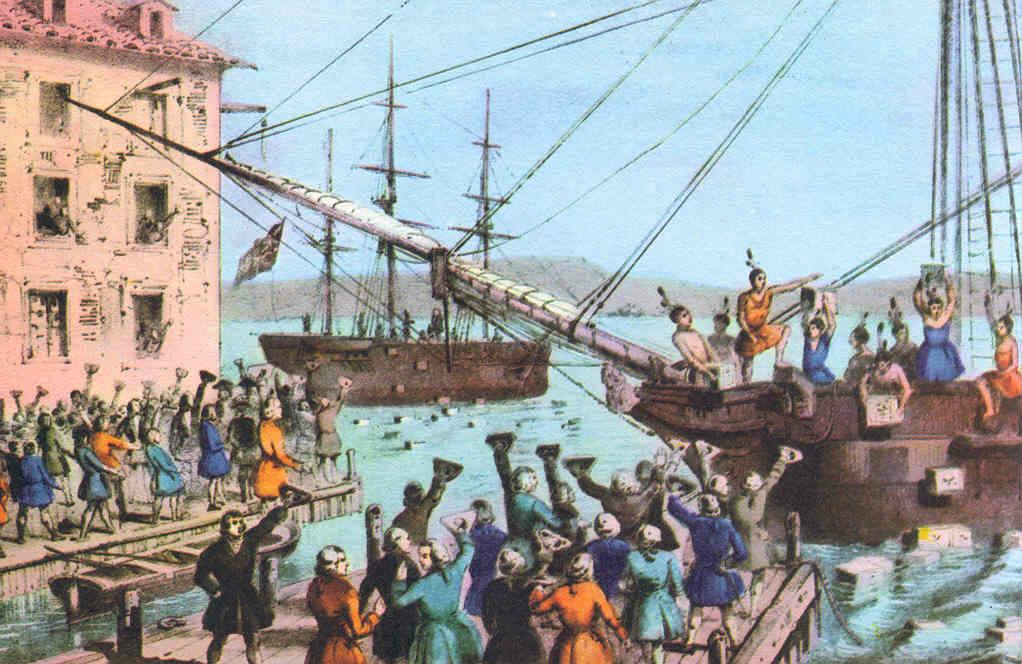

Then, just to make things come to a boil, George made the mistake of trying to control the American economy, placing taxes on goods coming and going to and from America, and then forcing the Americans to buy the very expensive British tea rather than the much less expensive Dutch tea. And when, in 1773, the Americans chose to show their displeasure over such royal highhandedness by refusing to unload such just-delivered tea, even dumping some of that English tea into their harbor at Boston, George was furious.

He was determined to break their spirit in every way possible. He particularly targeted strongly independent-minded Boston, by putting even the private lives of the Bostonians under the grip of his military, by stationing troops in their homes.

But ultimately all he achieved was to make the Americans even more resolved to keep his royal hand out of their affairs. Thus in 1774, colonial representatives came together in Philadelphia, the First Continental Congress, to spell out their grievances, and what they hoped to see happen in London to correct matters (they actually had a number of “Whig” supporters there in the British Parliament).

But George personally remained unmoved, and proceeded to try to disarm the restless colonials militarily, causing fighting to break out in Boston (actually just outside of the city) in 1775 between a determined and quite capable American militia (though much smaller in number), and the well-experienced British troops sent to America to force the colonials into submission.

War was now on. Indeed, in 1776, representatives to a Second Continental Congress drew up a Declaration of Independence, to make quite clear the American political cause, and their intentions to defend themselves no matter what.

At the same time, each of the colonies declared themselves now to be fully independent, fully sovereign societies, governed by their own state governments (and their respective legal foundations or state “constitutions” now undergirding each one of them).

Quite normally, such a struggle between sovereign king and rebellious commoners had one guaranteed outcome: defeat and severe punishment of the rebellious commoners. But that was just not going to happen in this American case. And there were a number of reasons that the American rebellion defied all normal expectations as to its outcome.

First of all, ruling monarchs never had to face a spirited people such as these Americans, well-disciplined in this matter of political self-management. Again, they had been at this program of self-government for about a century and a half.

Then also the spiritual Great Awakening had confirmed that spirit in a very special way, giving the colonials even greater confidence that their power to live freely as they did came from the gracious support of a caring God, not from some distant royal authority. And if faced to make a choice as to which of those two power sources they were likely to follow, for most Americans the choice was to let God, not King George, direct their lives, even in battle. In fact, especially in battle.

THE VITAL ROLE OF AMERICA’S LEADERSHIP

Then there was the matter of leadership, critical to the success of any social venture. Taking on the British king was going to take some true wisdom, bravery, and resolve on the part of those called to make the major decisions as to how the American effort was to move forward. And the Americans were truly blessed by having in their ranks some of the most outstanding leadership in human history.

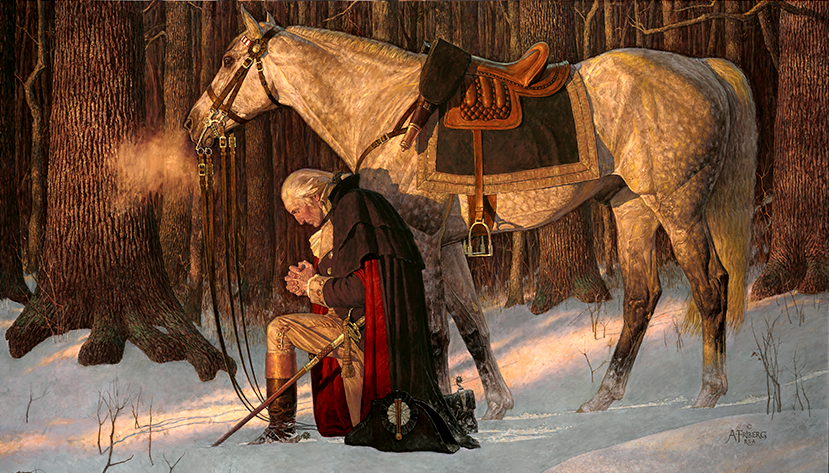

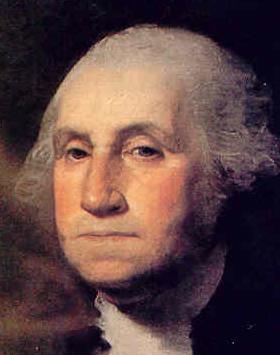

George Washington

It was an act of great wisdom for the Second Continental Congress in 1775 to call on George Washington to command the colonial armies fighting to defend American independence. Probably the self-understood wisdom at the time was simply that in choosing this Virginian to lead the troops, this would serve to deepen the South’s commitment to this act of independence, when the matter of the South’s involvement in this action was still rather uncertain.

But what they did not know at the time was what a Providential decision that this happened to be, “Providential” in the sense by which at that time they used that term to refer to God and his powers. A true Man of God Washington happened to be. And that would be the most important component undergirding his powerful leadership, even though that was not yet understood.

Washington was an experienced soldier. But so were others, in some cases even more so, which caused resentment on the part of some other American military leaders, undertaking even dangerous backstabbing on their parts.

But Washington was not interested in the ego games that drive so many people who have succeeded in moving themselves to public notice. Washington’s sense of self was probably secured by his own birth into Virginia nobility, although economic circumstances had made his growing up a constant economic struggle, which he took on quite graciously. In fact, this drew him even closer to God, well expressed in the diary he kept in those formative years. He well understood how rough life’s challenges could be. Yet he also developed the stamina to continue moving ahead, even when circumstances constantly seemed to want to undercut him.

He thus understood life on these terms, namely that we are called on by God simply to take up the duties laid before us, expecting the Evil One to try to discourage and even break us up, but all of this being simply the testing by which God brings people forward in fulfilling that call in life. Thus in all this, Washington was most certain that Providence was with him, as God had been with ancient David as he faced Goliath (and then later, King Saul in his effort to bring David down), and others called to critical social roles in history.

Consequently, with only a volunteer militia to lead, Washington was directed to fight off an experienced army of British troops many times the size of his, and to not falter when all of that was thrown his way.

Needless to say, finding any success in such an unmatched contest would at first bring mostly huge disappointments. But when others would have given up, Washington would not. And thus little by little, Americans understood that they had a real leader in command of their troops, ready to fight on until the will of the enemy to continue was finally shattered.

And finally, having Providentially found himself and his troops (and French allies) well-placed around a trapped British army at Yorktown (1782), that British will was finally broken. Washington and his troops had succeeded, way beyond what any reasonable person could have ever expected. Thus it was that Washington at that point was well-understood to be a man of most exceptional leadership talents, ones that newly independent America knew clearly it would continue to need as it laid out its own future as a fully independent society.

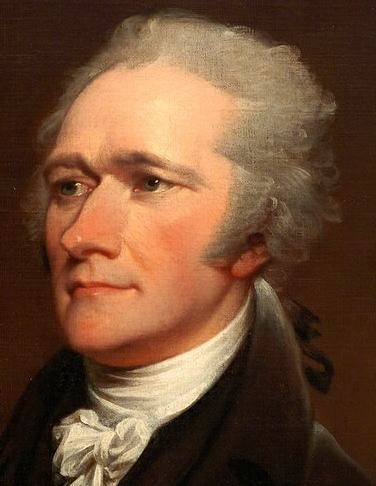

Alexander Hamilton

Washington’s closest associate was unquestionably the young Hamilton, whom Washington came to trust deeply. Hamilton was a man of great moral integrity (difficult to find in upper political circles), who, for instance, when having formed his own militia unit in New York at the war’s outbreak, was quick to defend and protect the president of the college he himself had attended (today’s Columbia University) when fired up anti-royalists wanted to lynch the man for his pro-British loyalties.

Hamilton was totally self-developed (raised under very poor circumstances in the West Indies as an orphan), bringing notice to himself because of his skillful mind and writing (at first used by Washington to write his military correspondence) and then given increasingly important assignments by Washington as the war progressed.

But one assignment Washington did not give, or did not want to give, Hamilton is when Hamilton insisted that he be allowed finally to join the action, by leading the final assault on the British at Yorktown. Thankfully, Hamilton was not killed in the venture!

Washington would then, in the future, continue to look to Hamilton for more such support and personal leadership. More about that later.

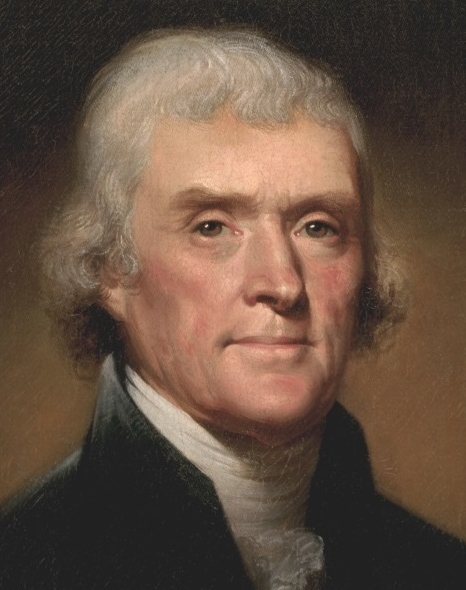

Thomas Jefferson

Much praise has been directed toward the person of Jefferson, particularly by the world of Rationalists, who consider Jefferson to be some kind of Rationalist patron saint.

Unlike Hamilton, Jefferson was born to upper class life as a Virginia aristocrat, and thus felt compelled to make that status clear in everything he did. And it was indeed this status that first brought him into the political world of the American rebels, when as a young man he was given the assignment to draft up what would become the Declaration of Independence, those asking him to do so not understanding what huge political significance would eventually be placed on this matter.

Much of what he came up with in that drafting was simply a rephrasing of what the British Rationalist Locke had spelled out in his writings, and much of what Jefferson came up with in that draft copy was simply cut out as being excessive in its line of reasoning. But the final product was judged to be a splendid testimony to Jefferson’s excellent “reasoning,” and that’s what brought Jefferson to the political front. Shortly after this he was elected as representative to the Virginia House, where he helped reshape Virginia’s laws as an independent state. Then in 1779 he was elected to be the state’s governor. However, in 1781, when the British finally turned their attention South towards Virginia, he and his government spent most of their time in flight from the British. This ultimately did not go over well with the Virginians, and he was not re-elected governor. Nonetheless, he was sent in 1783 as a Virginia delegate to America’s new Continental Congress, where he headed up the committee designing the shape and character of what were destined eventually to become new states in the American “Northwest” (territories in a region northwest of the Ohio River). Actually, it was his idea to make these non-slave territories, even though he was himself an owner of hundreds of slaves. Then in 1784, he was sent to Paris to negotiate new trade terms with the French … and in the process fell in love with the French lifestyle. He would remain there until just before the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, when he returned home, to then soon join Washington’s new Cabinet as Secretary of State, supposedly in charge of America’s diplomatic matters. More about this later.

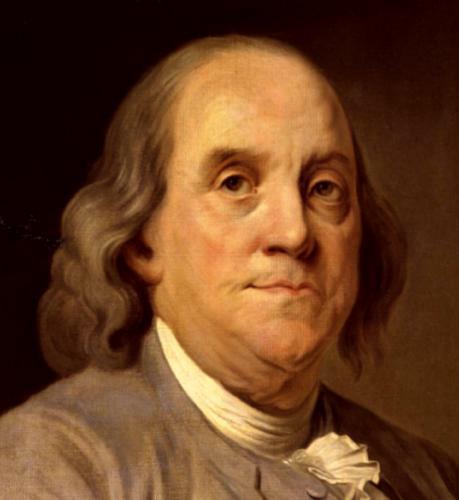

Ben Franklin

Franklin is a person hard to pin down as to what category socially he belonged to. He was born in Boston to a family expecting him to take up the family printing business, but escaped to Philadelphia to start up his own printing operations (including a newspaper). Eventually, beginning in 1732 and for 25 years thereafter, he was to publish annually a work, Poor Richard’s Almanac, offering advice, weather predictions, amusements, etc. This was to have a deep impact on “Middle American” life, and quickly bring him to widespread attention as a man of great wisdom! But even there, Franklin’s inquisitive nature would reach further, much further, in jumping him into the world of science (messing around with dangerous lightning!), math, and knowledge in general, Franklin helping to set up and then write the curriculum for what would eventually become the University of Pennsylvania. The assumption by many was that Franklin was a full-fledged member of the Rationalist club. He certainly could be a man of reason. Indeed, he was that, but more than that. Although he in no way fit into any standard Christian design of the day, he was a deep believer in God, and not just in a Deist way. He truly believed that events, not just those in the past but those even those in his own day, were shaped deeply by the hand of God, in accordance to the amount of faith man himself brought to the relationship. We have already mentioned his friendship with the most unorthodox Christian evangelist, Whitefield, whom he admired deeply. But here too, more about Franklin to follow.

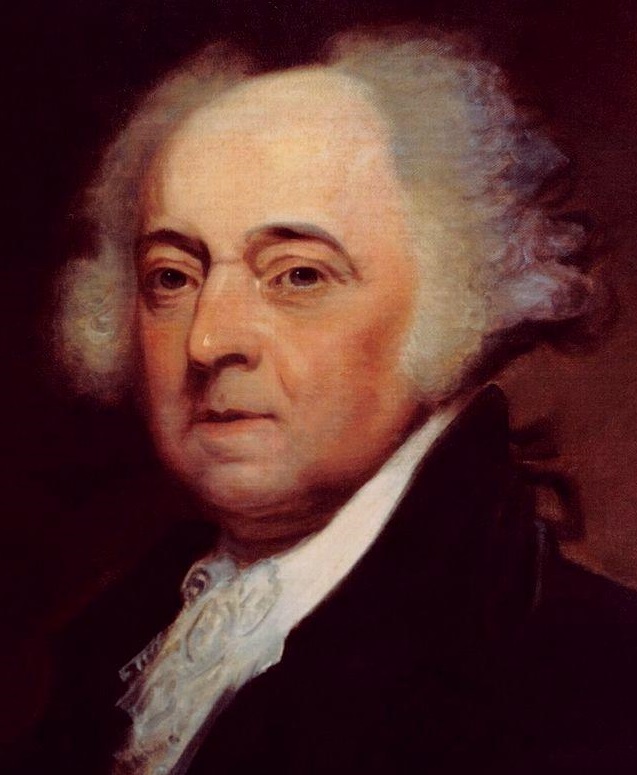

Adams was a complex man of conflicting principles, his Puritan background making him one who valued moral principle highly as a society’s necessary foundation, but also one who tended to employ a lawyer’s tactics in his efforts to achieve the political importance he hungered for so deeply. He was an early supporter of the idea of American independence and acquired such attention from his work (cases and writings) that he was called on to represent Massachusetts at both the First and Second Continental Congresses. At the latter, he headed the committee asked to compose the Declaration of Independence, he in turn asking Jefferson to do the draft, something he would regret for the rest of his life because of the fame it would bring Jefferson! He was sent to France to negotiate an American treaty with that country, and then was sent to the Netherlands as an ambassador, to get Dutch financial help for America, then back to Paris to participate in the negotiations leading to the American peace treaty with the British. Here too, more about him to follow.

BUILDING A NEW REPUBLIC

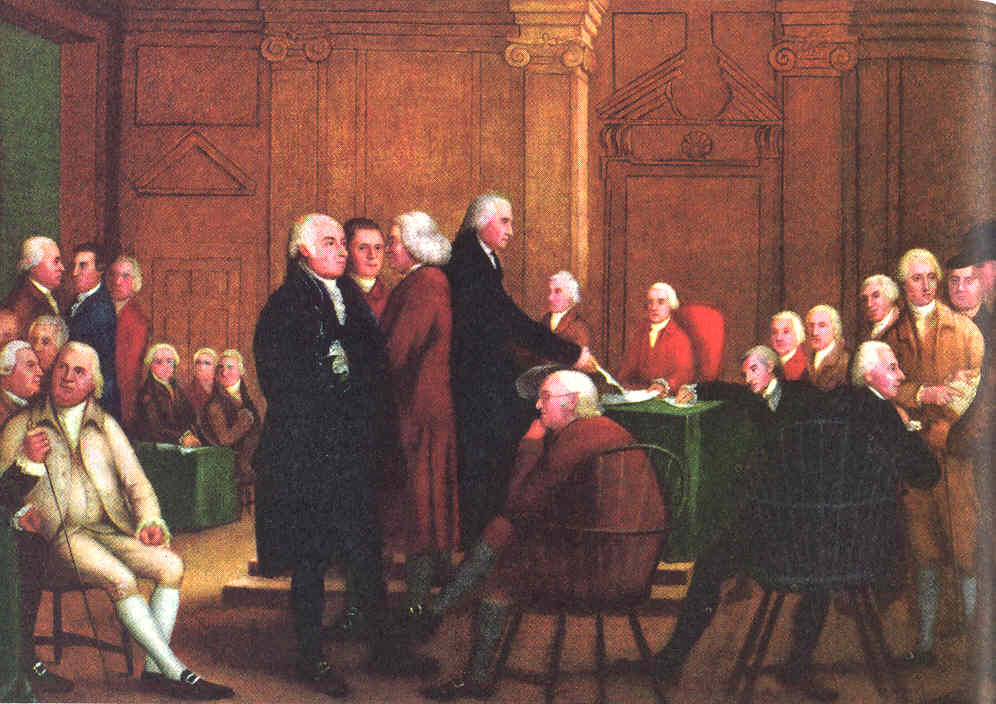

Coming up with a stronger political bond. Sadly, with their new full independence, the 13 new states found themselves competing deeply with each other: sending diplomats abroad to promote their state’s political interests, even setting up tariffs against each other’s products in order to encourage their own economies. This was a dangerous development, one which many of the leading political figures of the times understood quite readily. And thus in May of 1787, representatives of the newly independent states gathered in a cloistered “Independence Hall” in Philadelphia to try to work together, outside of the public eye, to come to some kind of an agreement bringing them back together … as the United States of America!

But, as also explained previously, very quickly it became apparent that this was as far as Reason was able to take them, before Reason descended into partisan bickering, especially as to how power was to be allotted among the states, states that were of unequal size and character. The biggest problem was that “logic” (logic of the big states anyway) therefore demanded that greater power should be accorded to the larger states.

Anyway, as also already noted, to achieve that deeply desired unity, it took Franklin’s intervention … plus the realization of the delegates themselves, that they were going to have to go higher than merely their own political logic if they were to arrive at this political unity America needed so badly. And indeed, finally by September of that year they achieved exactly that unity. And for that they knew that it had been God’s hand that had led them to just that achievement.

“A Republic, if you can keep it”

The representatives having met in secret all those summer months, when their work was finished and the doors were finally opened to the public, there was understandably great public interest in what these representatives had ultimately designed as their new American government. Was it a monarchy, a democracy, or what? Franklin answered calmly, when that very question was asked of him: “A Republic, if you can keep it.”

Wow! A Republic … if you can keep it! What was it that this very wise philosopher, teacher, scientist, was saying? Did he have his concerns? Of course he did. And anyone familiar with the game of politics would be wise to be just so concerned. America was going to need a lot of guidance to stay on course, on God’s course, and not wander off into some realm of self-destructive Human Reason. The Constitutional Convention itself had just proven that. Anyway, a Republic rather than, say, a Democracy? What did that mean?

Franklin (and the other delegates) knew that a democracy was a form of government conducted by the ideas, even whims, of the common people, one that history showed (as in the Greek case) was able to be easily manipulated by clever Sophists (“Wise Ones”) skilled at getting the people to believe anything at the moment, and capable of heading them off to some very self-destructive venture, one that seemed so “reasonable” to them at the time.

A Republic, however, was governance by a set of deeply embedded laws, constitutional laws that set the goals, boundaries and rewards for a particular society, laws not easily changed by the mere whim of political trends. In short, Franklin was saying that America was intended to be led by a regime of law rather than by ambitious, ever-shifting, human wills.

But the challenge was there. As we have already noted, Rome started off that way, a society directed by a strict set of laws (clearly defined on those 12 bronze tablets posted in the Roman Forum) and grew and prospered greatly as just such a Republic. But when “reformers” began to update those laws along more “progressive” lines, the Republic drifted from that firm legal-moral foundation, and fell ever-deeper into domestic social conflict. Ultimately, the Republic simply disintegrated … and had to be rescued from the resulting social-moral chaos by dictatorial emperors.

And thus Franklin’s “A Republic, if you can keep it.”

GOD’S HAND IN ALL THIS

Hamilton had experienced first-hand those well-reasoned contentions that initially looked as if they were going to cripple the effort to unite the various states under a single Constitution. He made something quite clear:

For my own part, I sincerely esteem it [the Constitution] a system which without the finger of God, never could have been suggested and agreed upon by such a diversity of interests. [A letter by Hamilton to Mr. Childs, October 17, 1787]

And as for James Madison, the Virginian aristocrat (but New Jersey educated, at what one day would be Princeton University) who kept the notes at the constitutional convention, and who joined Hamilton in writing the many Federalist Papers, published to demonstrate why it was necessary for all the states to fully ratify this Constitution, he would have something quite similar to say:

It is impossible for the man of pious reflection not to perceive in it [the Constitution] the finger of the Almighty Hand which has been so frequently and signally extended to our relief in the critical stages of the Revolution. [The Federalist Paper #37, January 11, 1788]

Making this same point quite clear, in his inaugural Address, issued in his assuming the office of President (April 30, 1789), Washington had this to say:

It would be peculiarly improper to omit, in this first official act, my fervent supplication to that Almighty Being, who rules over the universe, who presides in the councils of nations, and whose providential aids can supply every human defect, that His benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of the people of the United States. . . .

No people can be bound to acknowledge and adore the Invisible Hand which conducts the affairs of men more than the people of the United States. Every step by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation have been distinguished by some token of providential agency. . . .

[We] ought to be no less persuaded that the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right, which Heaven itself has ordained.

Thus it was, thanks greatly to the Christian Great Awakening and the soon-to-follow intense challenge of the war to secure their independence (and find agreement afterwards as to how they could continue to work together in facing the unfolding future) that America was still a “God-fearing” nation, Americans’ understanding the critical importance of building their new nation on the same Protestant-Christian foundations set out by colonial America 150 years earlier. These moral-religious foundations had served them very, very well.

And indeed, they were quite aware of this fact.

But would they be able to stay the course, letting their faith in God continue to be their supreme guide? Or would they, over the coming generations, turn to man’s more “natural” instinct of relying on self-justifying (thus greedy) political, social and economic reasoning … the same self-destructive path that Adam and Eve took up in believing the grand deception of the Evil One, namely that eating the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil (Human Reason) would make them like God. In doing so, these Biblical ancestors lost their Divine protection and guidance, and were then forced to live facing the usually-not-very-pretty consequences of their own designs and deeds. Tragic!

Anyway, at this point, the United States of America was off and running!

Go on to the next section:

The Early Years of the Republic

John Adams

John Adams