CHAPTER TWO

AMERICA’S COLONIAL FOUNDATIONS

VIRGINIA AS ENGLAND’S FIRST EFFORT IN AMERICA

Dealing with Spain. Watching the Spanish grow rich from American gold was hard for other European powers to observe. But getting in on that act would be a matter nearly impossible to carry off. The Spanish navy guarded closely the Atlantic, to make sure that it remained under full Spanish control. Of course “privateers” (pirates), of which the English seemed to have quite a number, busied themselves raiding and plundering what they could of the Spanish fleets transporting American wealth back to Spain.

Finally Spanish King Philip of Habsburg had enough of such piracy … and was determined to bring the source of such criminality, England, under Spanish control. But he had other reasons for wanting to do so as well. He had, in 1554, just two years before he began his reign as Spanish king, married English Queen Mary Tudor … adding substantially to his Spanish-Catholic realm. But Mary had suddenly died in 1558 … and her place in power in England was taken by her relatively pro-Protestant half-sister Elizabeth. Thus not only had Philip lost England in the deal, his beloved Catholicism (he hated Protestantism intensely) seemed also to have taken a big hit in England.

Thus it was finally that he had enough of England and its “evil” ways … and sent his mighty naval fleet, the great Spanish Armada, to conquer England (1588). But things did not work out as planned … when horrible weather and clever English seamanship together destroyed his fleet.

This would mark the beginning of Spanish decline … and the rise to power of the English.

The French get involved. Most importantly, the Spanish seemed to have had very little interest in laying claim to the lands of what constituted North America. The French thus had responded quickly to the opportunity for territorial claim in America by sending the French explorer Jacques Cartier to lay claim in 1534 to a “New France” in Canada. They would plant a number of colonial settlements … none of which succeeded because of weather (Canada), lack of resupply (South Carolina), or Spanish opposition (Florida). Finally, in 1608, Champlain established a successful French settlement along Canada’s St. Lawrence River at Quebec. And they would eventually reach even beyond that, all the way to the Mississippi River valley – La Salle claiming that region as French territory in 1682.

Jamestown, and the gold motif. The English also wanted to get in on the act, and saw the lands between New Spain in the South and New France to the North as offering them just that opportunity. They first (1587) sent off a community of 90 men, 17 women and 11 children to found an English community (“Roanoke”) along the Outer Banks of today’s North Carolina. But plans to continue to support and resupply that venture got curtailed by the Spanish effort to conquer England. When in 1590 they finally were able to get a ship to bring such supplies to the Roanoke Colony, its inhabitants had disappeared – with no indication of what had happened to them. Needless to say, that had a huge impact, discouraging further English plans for such colony-building in the New World.

But ultimately, the gold lure proved to be a very strong motif for trying again in 1606 to organize an English settlement in America. And it was not just the acquiring of wealth that inspired English gold hunters. Those that were recruited to venture off to Virginia agreed to this very dangerous mission because it was well understood that the acquiring of such wealth in American gold would also allow them to buy land, hopefully lots of land, and thus improve greatly their own personal status within the highly-stratified English social system, at least within the still-feudal parts of English society.

However, a major social problem developed immediately upon these settlers’ arrival in Virginia in May of 1607. Personal greed not only inspired their behavior, it made the social cooperation necessary for their collective survival impossible to attain. Upon arrival to Virginia, the men (there were no women in the first group) quickly set up something of a fortress at “Jamestown,” named after England’s presiding king, and then headed off to find for themselves the gold that would make them rich.

But as things turned out, no significant amount of native gold was discovered. And worse, their unwillingness to work together as a community left them very weak in the face of the huge life-threatening challenges that surrounded them. Consequently, they died in massive numbers.

More men were brought in (and women too beginning the next year), not yet fully aware of the problems impacting the settlement, and they too died, by the hundreds. Indeed, in the winter of 1609-1610, 420 of the 480 colonists died.

Tobacco. Two things finally saved the Jamestown plantation from becoming another failed venture. One was the arrival that summer of 1610 of the English commander Lord De La Warr (Delaware), and more settlers and supplies, which brought some degree of order to the Jamestown social mess. And the second thing was the subsequent discovery (around 1612), thanks to John Rolfe, that the drug tobacco could bring to the planters the wealth that they all dreamed of, the wealth that would raise their social status greatly.

Thus additional family-based settlements or plantations were soon established along the shores of the various rivers of the Virginia Tidewater region (principally the James, York, Rappahannock, and Potomac Rivers) where the tobacco could be farmed in mass amounts by indentured workers brought in from abroad. And most marvelously, because of the depth of these rivers, the tobacco could then be shipped directly from these riverfront plantations all the way to England. Virginia would need no urban commercial center to consolidate and ship their tobacco for them.

Thus urban Virginia did not develop. Virginia took on more the character of rural rather than urban Europe, a society led by Virginia “aristocrats” whose families owned the rather large estates bordering the rivers. It all resembled quite closely the Europe that was still living under feudalism.

Sadly, those that came along later to settle the Virginia colony found that, with the prime riverside lands already well settled, the only available land for them to undertake their own tobacco farming was further inland, in the rocky uplands, at some distance from the great rivers, and where hostile Indians awaited them. These later plantations would exist economically only very marginally. Ultimately, many Virginians ended up qualifying only as poor dirt farmers.

Nathaniel Bacon confronting Virginia governor Berkeley over the lack of protection of the Virginia workers and frontier farmers – 1676

With Englishmen becoming increasingly aware of these developments in Virginia, the Virginia settlement slowed up in its growth.

Slavery. Also, “indentured” or contracted laborers to do the labor were hard to keep in place (their terms of service were actually fairly limited), and thus the Virginia aristocracy found that purchasing African slaves, who would serve these aristocrats for a lifetime, and the slaves’ offspring after them as well, proved to be a “necessary” investment. And then also, the amount of slaveholding, in addition to the amount of acreage under cultivation, became quite the measure of a Virginian’s social status.

Thus by the beginning of the 1700s a number of aristocratic or noble families dominated Virginian life. For instance, there was the Byrd family, proud owners of a library of around 4,000 volumes at their plantation home, and owning hundreds of slaves and almost 180,000 acres of land. That was quite the feudal estate!

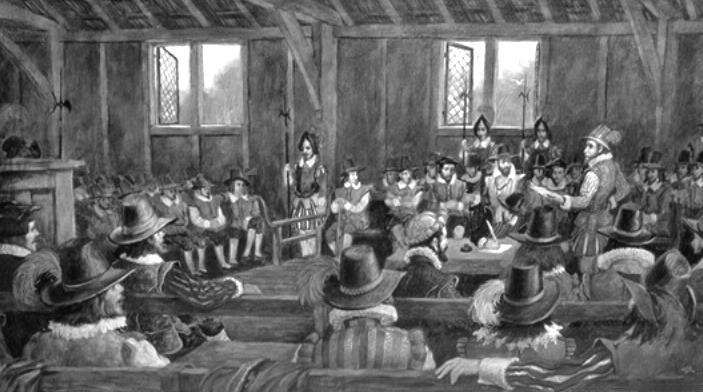

Government. Virginians rightly like to point out that it was Virginia that first established “democracy” in English America. Indeed, something resembling very much the English Parliament of the day was set up in Virginia in 1619, the House of Burgesses, with each county sending two representatives to Jamestown for periodic meetings to discuss matters impacting Virginia.

Especially important in this arrangement was the Governor’s Council, something like the British House of Lords, involving select individuals called to work with the royally-appointed Governor. But even the representatives to the House were typically drawn from the ranks of the Virginia “gentry,” this being the expected role of those of a higher social rank.

Spirituality. And yes, it was a “Christian” society, at least in name. But settlements were widely scattered, making regular church attendance difficult. Anglican priests were few in number. And religion itself had actually played no role in getting the colony up and running. And widespread slavery should have raised some Christian questions, but ultimately didn’t.

Again, in the context of the time (1600s and 1700s), this quite “feudal” rural order was all very much the political norm of the day in Virginia, just as feudalism was still the norm in much of Europe.

THE NEW ENGLAND COLONIES

Calvinist Puritanism. What was most definitely not the norm of the day was the English plantation that developed in New England, because from its very founding, it was an experiment in trying to live in accordance with particular social principles, principles directly drawn from the Calvinist Reform Movement that birthed a number of different Protestant communities in Europe, and in particular, the Puritans of England.

“Puritan” was originally a term of scorn issued by English religious traditionalists, who were very unhappy with those wanting to “purify” the Anglican Church (the Church of England). These English Puritans were very opposed to all the fanciful Sunday rites and rituals conducted at an altar by fashionably-dressed priests, and instead urged their religious leaders (preachers or pastors) simply to teach and encourage the faithful through their Sunday sermons … about how God wanted them to go at life − a life of faith in God and a caring for each other − the way Jesus himself set the example.

Puritans vs. Separatists. Of course, once the idea of such religious reform got underway, it quite naturally would take a number of various forms. But Puritan pastors were fairly uniform in holding to their idea that what their Christianity was to be all about was what the Bible itself showed them their religion to be, nothing more, but certainly also nothing less.

But a deep split occurred within the English Puritan community about how long the effort to reform the Church of England was to go on. Many were already quite ready to “separate” from the Anglican Church, and thus got the label “Separatists.” The Puritans who stayed with the original idea of Anglican reform looked down on these Separatists as “quitters,” and in general viewed them with deep contempt.

It would be this Puritan-Separatist split that would set the groundwork for what was soon to develop in New England.

With the arrival on the throne of James I Stuart in 1603, supposedly himself a Protestant with something of a Scottish Presbyterian background, there was much hope that he might himself undertake some of the reforms that the Puritans wanted so badly. King James did authorize the publication of a new English translation of the Bible (1611), though most Puritans continued to cherish their English-language Geneva Bibles (the New Testament printed in 1557 / the rest of the Bible in 1560).

With the arrival on the throne of James I Stuart in 1603, supposedly himself a Protestant with something of a Scottish Presbyterian background, there was much hope that he might himself undertake some of the reforms that the Puritans wanted so badly. King James did authorize the publication of a new English translation of the Bible (1611), though most Puritans continued to cherish their English-language Geneva Bibles (the New Testament printed in 1557 / the rest of the Bible in 1560).

But beyond this Biblical support, James was unwilling to go, realizing how much Puritanism undercut his importance as the reigning and ruling hand over the Church of England. But basically, he moved cautiously in the matter, not liking the Puritans, but not really taking them on, the way other monarchs had taken on Protestant reformers in their countries on the continent.

But for the Separatists, he had no mercy whatsoever, and set about the task of trying to eradicate them and their movement.

The Separatist “Pilgrims” to America. And this would be what would cause a congregation of Separatists at Scrooby in northern England to flee England (1608-1609) and relocate themselves at Leiden in the Calvinist Netherlands. But conditions there were harsh, for the Protestant Dutch were under constant attack by the merciless troops of the ultra-Catholic Spanish king. Also, urban jobs for these Separatists were hard to find (being mostly farmers themselves originally), and, as the years went by, their children were taking up Dutch, not English, ways.

After about ten years of struggling to get themselves set up in Leiden, the decision was finally made to leave Leiden, and, under William Brewster’s spiritual guidance and John Carver’s political leadership, head for the New World, supposedly to “Northern Virginia.”

The situation was very tricky because the character and motive of this group needed to be declared cautiously, and they would need financial support from backers, or “adventurers” as they were then termed. To get that support they would have to pledge their lives in humiliating economic ways.

But eventually the arrangement was made. And, after a major mishap in losing one of their two ships and thus having to return to base in England, they finally got off a second time (September 1620), a very late start and with everyone cramped together on one ship, the Mayflower. But then storms at sea drove them well north of their intended destination, and they finally arrived at what their maps indicated was Cape Cod. This was not Northern Virginia, but instead, well north of that, in the region which had just been designated as “New England.”

At that point they had to reinvent themselves legally, and came up with a contract pledging mutual service to each other (understanding very well from the stories of Jamestown the dangers to a new settlement of selfish behavior on the part of the participants): The Mayflower Compact, signed just as they were about to leave the ship to explore the area where they had landed.

And it was a terrible winter they then faced, lacking food, adequate housing, and coming under such sickness that only a few of them were healthy enough to take care of the others, half of whom died that winter anyway, leaving only 52 of the original 102 to carry on. Among the dead was Governor John Carver … consequently replaced by William Bradford.

But something about their spirit made them rebound quickly under the circumstances. And miraculously aided by an English-speaking native named Squanto, over the coming summer the survivors indeed planted themselves quite capably at the site they termed “Plymouth.”

And in the years ahead, more settlers were able to make their way to the Plymouth Colony … although at the time no one thought it to be anything very notable. They were just a colony forced by religious necessity to find some way to survive. And survive, the colony did … and quite nicely.

And they knew they had God to thank for that. That was one thing that these Calvinist Separatists were very clear about. They well knew beforehand the chances of devastation that awaited them in coming to America, as “pilgrims” (our term, not theirs). Virginia had already made that clear. But they valued greatly their amazing success (no more “dying time” for them after that first winter disaster) and knew that it was God, not human cleverness, that had made all of that possible.

The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth – by Jennie A. Brownscombe

The Puritans now also take up the American challenge. But within five years of the arrival of the Separatist Pilgrims to America, the situation back in England for the Puritans suddenly became very harsh under Charles I, the new king being very strongly opposed to any kind of Protestant reform. Thus a growing number of Puritans began to realize that they too were going to have to self-qualify as Separatists. They too were beginning to conclude that it was time to move on, and leave religious reform in England behind them. As dedicated Puritans, they understood that they had a job to do, a commission to fulfill. But it was to take place not in England, but in the New World. They were, like the Separatists before them (whom they quickly came to respect), to move themselves to New England, and continue their grand social-moral-spiritual reform there.

And they knew furthermore that God was expecting their work to serve as a much larger Christian mission to the wider world. They were to set up a model society in America that would guide others to live socially the way God intended all of his human creation to live. They were to be a people living in and for the very spirit of Christ, shown very clearly in the life and ministry of Jesus as to how God wanted all humans to live. They were to model just such a Christian life.

This was a huge and very serious endeavor they were to undertake. And it was not just a matter of survival in the harsh conditions of the New World. God would be with them, would protect and lead them in their encounter with the adversities that awaited them in the New World. But they had a job to do, and if they failed to complete the mission that God was sending them on, then they would have disaster awaiting them.

They well understood that their true challenge was spiritual, even though serious material or physical challenges certainly also awaited them in America. But their strong faith informed them that God would take care of these latter problems, as long as they looked to staying strong in the former matter, the spiritual matter.

And for that, they would find their mission led by pastors, lots of them (unlike Virginia which had very little of such spiritual direction).*

These Puritan pastors were expected to gather their “flocks” locally on a weekly basis and, in sermon rather than in religious ritual form, coach them, encourage them, guide them, and correct them if necessary, so that their work was done in accordance with God’s covenant with them. That, after all, was the real dynamic that Puritan New England was going to try to live by, and show the rest of the world how that could be done.

The unsuccessful Salem effort. Sadly, the first Puritan group to head to New England (1627-1628) did not fare well. In addition to a very harsh winter that the settlers were unprepared for (over 80 died as a result), a series of religious disagreements that Puritan leader John Endicott was unable to resolve discouraged deeply this new group of settlers. Thus in 1629, of the 300 original settlers, only 80 remained to try to continue the experiment, with the others returning to England.

John Winthrop. But truly a “man of God” came forward at this same time to take up the Puritan challenge: John Winthrop, actually America’s first great “Founding Father.” Winthrop was nobly born (but having an amazingly humble heart), a member of Parliament, and deeply dedicated to Protestant reform of the Anglican Church. But when King Charles dismissed the largely Puritan Parliament in 1629, this closed down the possibility of any reform. But it also freed Winthrop now to spend his time organizing a massive effort to send thousands of Puritans to New England. And by the spring of 1630, he had a fleet of ships ready to send 1,000 of the first group of the 20,000 Puritans who would move to America over the next twelve years.

John Winthrop. But truly a “man of God” came forward at this same time to take up the Puritan challenge: John Winthrop, actually America’s first great “Founding Father.” Winthrop was nobly born (but having an amazingly humble heart), a member of Parliament, and deeply dedicated to Protestant reform of the Anglican Church. But when King Charles dismissed the largely Puritan Parliament in 1629, this closed down the possibility of any reform. But it also freed Winthrop now to spend his time organizing a massive effort to send thousands of Puritans to New England. And by the spring of 1630, he had a fleet of ships ready to send 1,000 of the first group of the 20,000 Puritans who would move to America over the next twelve years.

And he was well aware of how to ensure that this effort would indeed succeed, succeed magnificently. He not only made sure that the much-needed material support would be available for these settlers, he was very strong in his insistence that this endeavor would plant the very necessary spiritual foundations needed for social success.

And those spiritual foundations were not merely add-ons to the venture. They were the very heart of the whole endeavor.

He made that very clear in his sermon, A Modell of Christian Charity, one that he delivered to that first group of settlers as they all gathered in preparation for their departure.

He viewed this whole venture as something quite similar to the situation facing the ancient Hebrews as they were about to enter God’s Promised Land (1400 BC?), reminding them of what Moses, their Hebrew leader, told the gathered Hebrews as they were about to make this move. Thus Winthrop tells them:*

Beloved, there is now set before us life and death, good and evil, in that we are commanded this day to love the Lord our God, and to love one another, to walk in his ways and to keep his Commandments and his ordinance and his laws, and the articles of our Covenant with Him, that we may live and be multiplied, and that the Lord our God may bless us in the land whither we go to possess it.

But if our hearts shall turn away, so that we will not obey, but shall be seduced, and worship other Gods, our pleasure and profits, and serve them; it is propounded unto us this day, we shall surely perish out of the good land whither we pass over this vast sea to possess it.

Therefore let us choose life, that we and our seed may live, by obeying His voice and cleaving to Him, for He is our life and our prosperity.

And being the one called to lead this “New Israel” to the “Promised Land” in America, Winthrop would have his deep challenges. There would be multiple villages to set up, land distributed as equally as possible … in order to assure that social equality, not social climbing (more typical of natural human instinct), would characterize the venture.

The Puritans were also a people well-recognized for their personal industriousness (a solid “work ethic”), not only unafraid to “get their hands dirty” (as aristocrats refused to do) but seeing such personal labor as a requirement that God had placed on them: to work in his vineyard. Not surprisingly, their hard work also tended to prosper the Puritans materially, yet they looked upon flashy displays of wealth and status as unbecoming of any Christian, especially as God loved all people equally, and so should they. All of this together, a strong personal work ethic, a high level of literacy and an egalitarian social ethos shaped by their Christian faith, would go on to form the foundation of what I like to term “Middle America.”

Early voices of dissent.  Nonetheless, Winthrop would have a number of challenging personalities to deal with. There was the brilliant but loudly critical pastor Roger Williams, for whom the Massachusetts Puritan society was never pure enough, and who was invited finally (1636) to set up his purer society elsewhere, eventually the Providence colony next door in Rhode Island.

Nonetheless, Winthrop would have a number of challenging personalities to deal with. There was the brilliant but loudly critical pastor Roger Williams, for whom the Massachusetts Puritan society was never pure enough, and who was invited finally (1636) to set up his purer society elsewhere, eventually the Providence colony next door in Rhode Island.

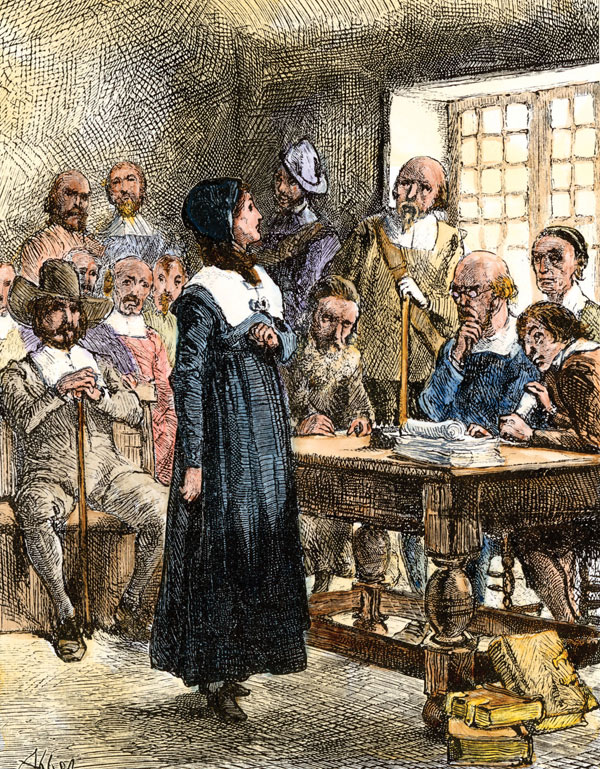

And there was Anne Hutchinson (loved greatly by today’s feminists) who gathered a group of complainers, she justifying their noncooperation with the accusation that all the pastors of the colony, except for her beloved pastor John Cotton, were instruments of the devil, spiritual frauds who were destined to bring God’s wrath on the colony.

And so things went.

Nonetheless, Winthrop, Williams, and Hooker found that, despite their initial differences, it was very advantageous to continue to work closely together, visiting each other in order to share concerns and ideas.

Thus indeed, despite their differences, these Puritans would hold to that original covenant or contract they had taken out with God, to serve him, and be protected and guided by him in the process. And they would experience just that prosperity promised them in that covenant relationship, as long as they held to that covenant. And indeed that would carry them forward, at least for the coming generation or two.

MORE COLONIES

Catholic Maryland. At about the same time that the Puritans were beginning to move to America to get away from religious persecution in England, the Maryland colony was founded for much the same reason, except it was set up for Roman Catholics escaping persecution in a heavily Protestant England. Behind this effort was the Calvert family, recently converted to Catholicism, who wanted a place of refuge in America for fellow Catholics, but also an opportunity to add to the family’s aristocratic landholding. But there were not many Catholics wanting to take this opportunity, so the Maryland colony was opened up to settlers of all faiths. Actually, the Protestants would outnumber the Catholics even from the very beginning. But the colony would remain quite religiously tolerant, and prosper accordingly.

In most respects Maryland differed very little from its neighboring colony, Virginia, just to the south across the Chesapeake Bay. Tobacco was the main crop, at first worked by indentured laborers, and then over time by slaves. The colony was dominated by an aristocracy, set up early by the Calverts, who gave large land grants to family members and fellow English gentry, creating in Maryland a distinct upper class that stood socially far above the common dirt farmers who came to Maryland as indentured workers.

The Middle Colonies of New York and New Jersey. While the English were settling the areas of Virginia and New England, the area between these two English regions was being settled (1620s) by a Dutch commercial company as “New Netherland.” The company established its capital at Nieuw Amsterdam (the future New York City) and sent settlers up the Hudson River and across the “Long Island” (such as the Roosevelts, who settled both areas) to develop the region as Dutch territory.

But the European Dutch and English, though both Protestant, found themselves deeply engaged in commercial wars, and, as a consequence, the Dutch colony changed hands several times during the 1660s and early 1670s, as the fortunes of war shifted back and forth.

New Netherland governor Peter Stuyvesant warned of the English threat

Eventually the colony ended up completely in English hands in 1674, in fact as feudal territory awarded by the English King Charles II to his brother James, Duke of York, and thus the new name of the colony: New York.

James never visited his American colony but governed it through a series of appointed governors and eventually (1683) an elected Assembly. But by and large the colony, with strong Dutch Protestant roots and a variety of other ethnic and religious groups present in the colony, was quite diverse in its cultural makeup, giving the colony a very cosmopolitan character virtually from its founding.

What came to be called New Jersey was also part of the Dutch territory awarded to James. But he turned around and in 1665 awarded sections of this grand new feudal estate to personal supporters of his own, the Carterets and the Berkeleys (a Berkeley brother was also Governor of Virginia at that time, and the Carterets and Berkeleys were also involved in the development of the Carolina colony at that same time).

Ultimately William Penn also became part of the New Jersey project when Berkeley sold his shares to Penn in 1676, who was looking to provide a place of refuge for fellow Quakers (Penn was himself a recent convert to this new Quaker form of Christianity), who were coming under attack for their peculiar ways (termed “Quakers” for their behavior when they became “overcome” by the Holy Spirit). But Penn would soon come into even more land for his Quakers.

The colony of “Penn’s Woods” (Pennsylvania). The Penn family, headed by a prominent admiral in Charles II’s royal navy and a key figure in the return of Charles to the throne, had lent the Stuart kings a vast amount of money in getting the Stuart monarchy restored to power after a brief English experiment in Republican government (1649-1660) under the Puritan leader Oliver Cromwell and his son Richard had failed. An agreement by Charles to pay off that enormous debt was struck when the king’s brother James agreed in 1681 to turn over to William Penn the vast lands west of New Jersey, a land the king himself named Pennsylvania (“Penn’s Woods”). Here Penn could expand his Quaker refuge, and build an ideal city, Philadelphia (the city of “Brotherly Love”).

The colony of “Penn’s Woods” (Pennsylvania). The Penn family, headed by a prominent admiral in Charles II’s royal navy and a key figure in the return of Charles to the throne, had lent the Stuart kings a vast amount of money in getting the Stuart monarchy restored to power after a brief English experiment in Republican government (1649-1660) under the Puritan leader Oliver Cromwell and his son Richard had failed. An agreement by Charles to pay off that enormous debt was struck when the king’s brother James agreed in 1681 to turn over to William Penn the vast lands west of New Jersey, a land the king himself named Pennsylvania (“Penn’s Woods”). Here Penn could expand his Quaker refuge, and build an ideal city, Philadelphia (the city of “Brotherly Love”).

Years earlier, Penn had disappointed his father in not becoming a leading soldier and politician in England, but had shown only a very sentimental heart in his reaction to the suffering of the common people during the 1665 Plague and 1666 Great London Fire, which left them destitute. This had brought Penn to join the Quakers in servicing those needy individuals, but also earning him an eight-month prison term for working with the Quakers, despite his family’s high connections. Thankfully he was reconciled with his father as the father lay dying (1670), telling his son never to betray what his conscience knew to be true. Penn never would.

However, in getting Pennsylvania up and running (Penn came to the colony in 1682 to see things get started), Quakers were immediately outnumbered by other religious groups (Mennonites, Amish, Puritans, Presbyterians, Catholics, Jews, etc.), and Pennsylvania grew as a land offering freedom and the opportunity for people to build their own communities as they so desired. Pennsylvania contributed greatly to the growing notion that America was a land not of government restriction and social-cultural conformity, but of true opportunity for those willing to come and work hard to build their own world, in full cooperation with others of different political and religious ideals.

Penn comes to his colony in 1682

What is sad is that Penn not only devoted his life to seeing this grand social project going, he devoted all his family funds to the project, did not have the heart to collect the “quitrent” owed him by the settlers, and was cheated of his profits by his business manager, and thus bankrupted himself. This ultimately had him in and out of debtors’ prison. And he died quietly in 1718, believing that he had failed in life, totally unaware of what an awesome thing his efforts had brought to the world.

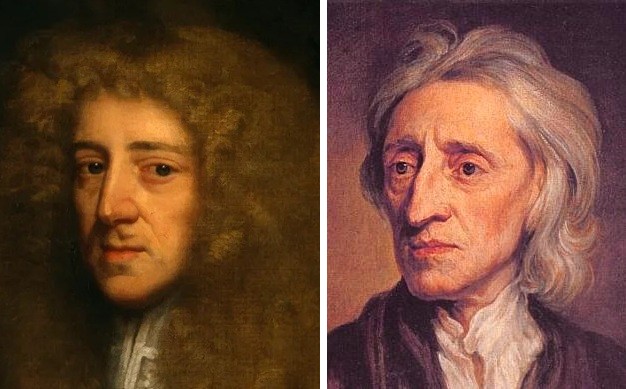

The founding of Carolina in the American South. King Charles II also repaid key supporters as proprietors of land to the south of Virginia, a vast colony which would be named after him (Carolina, from Charles’ Latin name Carolus). Taking the lead in this venture was Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, who enlisted the help of the famous English social philosopher and personal friend, John Locke. He wanted Locke to design a legal order for the colony that would make his colony a shining example of a society based on human reason rather than just on religious or political interests. Thus it was that in 1670 Locke came up with A Grand Model, which included the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, and a detailed program of property distribution based on a family’s social status. Unfortunately, much of Locke’s land distribution program had to be scrapped because Locke’s design and Carolina’s reality did not match up well.

Shaftesbury John Locke

However eventually the harbor at the Charleston site proved economically advantageous in its service to the rural hinterland, and individuals of all sorts of cultural backgrounds flocked there, including a good number of French Protestants or Huguenots chased out of France when in 1685 King Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, formerly protecting Protestant rights in France. Thus Charleston became the South’s first true city.

Georgia. Then in the early 1700s English general and philanthropist James Oglethorpe got the idea of planting a strategic military colony (named in honor of King George) at a site called Savannah, to the South of Charleston, to counter Spanish moves towards the north from Spanish Florida. Yet his plan also was to offer a new start in America to those who had fallen into debtors’ prison for economic failure (a very serious offense at the time). Anyway, settlers did come, not necessarily debtors however. But the colony took hold and Savannah went on to become the South’s second significant city.

Georgia. Then in the early 1700s English general and philanthropist James Oglethorpe got the idea of planting a strategic military colony (named in honor of King George) at a site called Savannah, to the South of Charleston, to counter Spanish moves towards the north from Spanish Florida. Yet his plan also was to offer a new start in America to those who had fallen into debtors’ prison for economic failure (a very serious offense at the time). Anyway, settlers did come, not necessarily debtors however. But the colony took hold and Savannah went on to become the South’s second significant city.

A SPIRITUAL WANDERING

As already noted, there is a distinct pattern in human life that repeats itself regularly in history, well recorded even in the ancient writings of the Hebrews or Jews. A generation faced with harsh adversity, and which turns to God in full faith for deliverance, invariably finds that faith to be well-rewarded by God-delivered miraculous success. But it only takes such success to allow a very comfortable future generation, for whom such challenges seem distant and merely only quaint stories about their ancestors, to wander from that special relationship with God. Their life now of leisure and material success has come to seem so “natural” that they lose sight of the vital understanding about how their ancestors’ faith in God was the essential ingredient in all of this.

Moses once warned the Hebrews that in the turning away of their hearts from God, all of this “natural” splendor would vanish, and inevitably they would find themselves again in dire circumstances.

And that is exactly how things went for the New England Puritans several generations later. Puritan youth born in a now-comfortable America were soon showing a declining interest in entering into the rigorous spiritual relationship with God typical of the first generation of Puritan settlers in New England. This relationship however still was considered necessary for those involved in directing the Puritan “democracy” that the Founders had set up. So a “compromise”* had to be reached in order to allow those entering adulthood some kind of a role in the direction of their communities. But that compromise was merely “part one” in that wandering, which in time would move them further and further away from the original Puritan idea.

By the late 1600s troubles seemed to be appearing everywhere. Materially speaking, the New England economy was suffering from the fact that the rocky soil on which this social experiment was planted was having an increasingly difficult time producing the agricultural needs of the rapidly expanding community. And most sadly, there seemed to be little that could be done about the matter

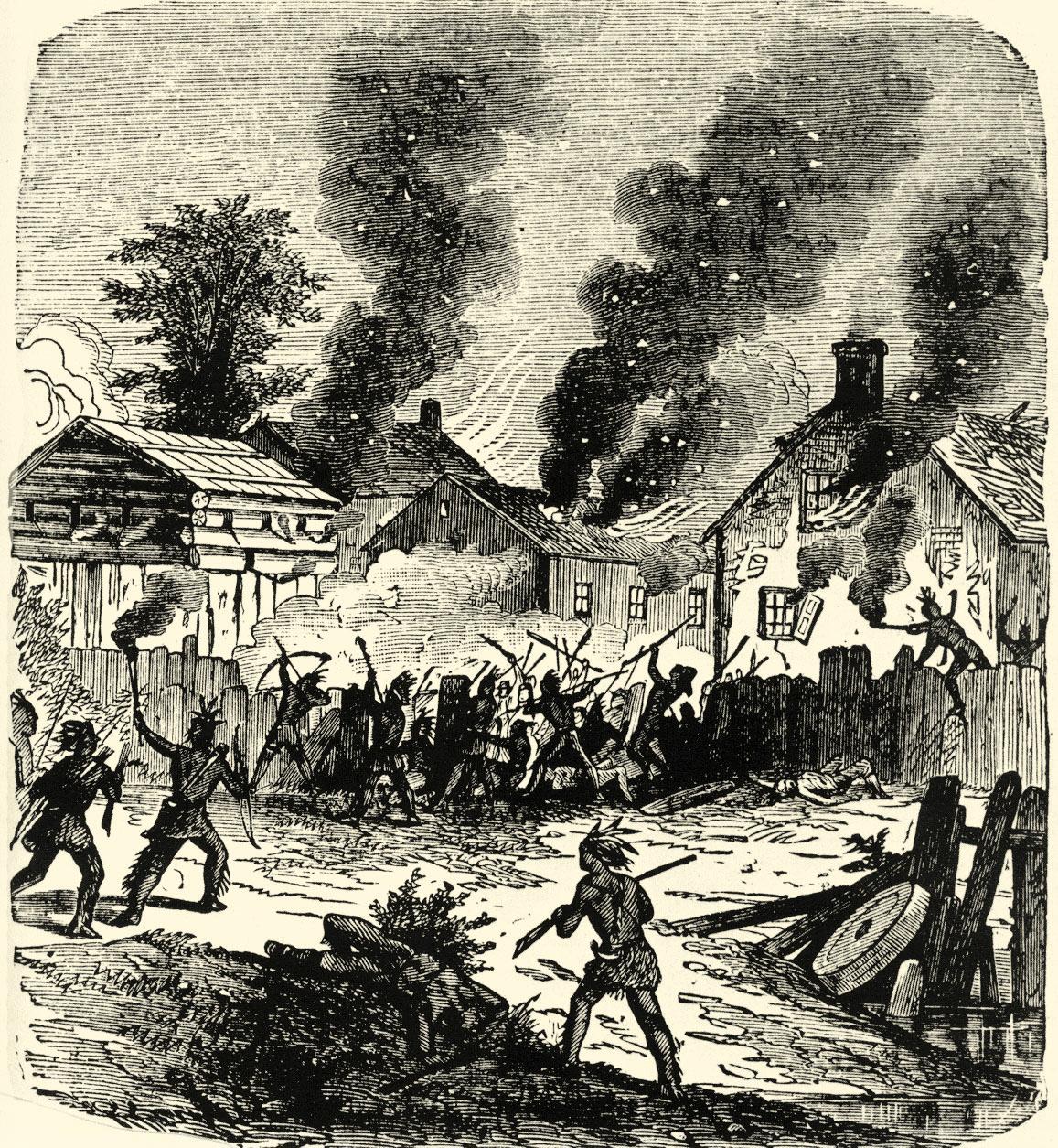

And the Indian tribes along the Western frontier were increasingly reactive to the spread of the English colonists into their hunting lands, and frequently attacked vulnerable communities along that frontier, slaughtering all the colonists they could, women and children as well as men. They spared no one, even as slaves, as they could not feed them. They simply wanted these intruders gone, gone, gone.

Indeed, in 1675, angry Indians attacked nearly half of the English villages, killing almost 1,000 English settlers in the process.

But the Indians had no way of following up on this “success,” and had missed a valuable planting season in doing so, and were themselves now in trouble. Ultimately one of them killed their warrior-chief Metacom (or “King Philip” as he was known by the English) and the uprising came to an end.

But most understandably, the Indians would find themselves, upon occasion after occasion, most ready to undertake some kind of action to stop the spread of the English across their hunting lands.

The “Rationalist” worldview grows in America

All of this was having a devastating effect on the “Puritan” world of the late 1600s, which, because also of the spread of British intellectual “Rationalism” (thanks to such British political philosophers as John Locke), had spread to the colonies the expectation that life should always work rationally, programmatically, under complete human design. This sadly had actually become the real religious faith of many of the Puritans at this point (“Puritans” in name only by this time). But when little at this time seemed actually to be working rationally, who was to blame? God was supposedly a good god, though seemingly very distant at that point. What then could explain this dark situation better than the simple ascendancy of evil, presided over by the Evil One.

The Salem Witch Trials

Nerves now began to fray. And it took only a small incident in Salem (girls telling a giant fib) to spark a horrible reaction (1692), one that blamed certain individuals (a growing number of them as the panic spread) to be instruments (“witches” even) of the Evil One. People were arrested, accused of practicing witchcraft, imprisoned, and even put to death … before Puritan authorities in Boston could bring the hysteria to a halt (early 1693).

Sadly, this most unfortunate event would be used, thanks to an effort to fight the growing ugliness of early-1950s McCarthyism (more about that later), to blame such McCarthyism on the same “Puritan” spirit that produced the hysteria of the “Salem Witch Trials.”* Most tragically, this would then come to be the Puritan legacy that a growing number of American intellectuals would want Puritanism to be remembered by, and thus be avoided at all costs, even though the events of those late 1600s had virtually nothing to do with Puritanism, other than still being the group-identity name of those involved. But this was hardly Puritanism.

And thus it was that the all-essential Puritanism that laid the foundations on which a quite successful America would then be built, would be discarded, even be remembered simply as some kind of period of great evil. But that’s what happens when history is offered up as just ideological reflection (supporting or opposing various ideas of the day) rather than as true and thus actually instructive narrative.

Rationalism digs in

Nonetheless, as America entered the 1700s, it seemed even more eager than ever to head down this new “Rationalist” path. “Deism” was becoming increasingly popular, in that God was considered to be merely the wonderful creator of the universe, wonderful in that he had created all this wonder to operate by very precise methods, methods that “natural philosophy” (as the field of science termed itself at the time) was coming to explore, understand, and ultimately put to work for the benefit of human life on this planet. Deists and others among the natural philosophers were glad to thank God for creating a universe so easily studied, understood, and put under human command. But as for the further need of such divine intervention, this group increasingly felt that natural philosophy had made that most unneeded, most unnecessary.

It was even considered to be a matter of huge foolishness to call on God to intervene to reshape earthly events. Such intervention would merely damage the beautiful order on which all of nature clearly depended.

And there was nothing holding back the move of such Rationalism into Christian theology, especially on the part of those most given to the world of philosophy. Christian writers and “enlightened” Christian pastors were themselves joining the world of such Deism, even Unitarianism, gathering to give thanks to God for creation’s splendors, but leaving daily matters simply to human design, ultimately to human self-interest. Examples of this were John Toland’s Christianity Not Mysterious (1696), or Matthew Tindal’s Christianity as Old as the Creation (1731), or England’s leading religious official, John Tillotson, Archbishop of Canterbury (1691-1694) … who saw Jesus simply in the role as moral instructor, not as some kind of savior of the unworthy. It all seemed so good, so rational, to go at life this way.

THE “GREAT AWAKENING”

But God was not finished with America. Without any warning, or any clear explanation of why, something very peculiar hit America. By the 1740s, America found itself caught up in a massive Christian spiritual revival, one that swept deeply and extensively through the colonies, from the north in Maine to the south in Georgia. Actually something of this nature had begun even in the 1720s, as a number of pastors took up the call, not to reassure their flock of God’s continuing blessings because of their proper Christian behavior, but instead to call them to repentance because they had come to misunderstand deeply what it was that God wanted from them: faith in him and not in their own good intentions and deeds. God was looking for followers, fellow family members actually, not just distant admirers. Thus such individuals as Theodore Frelinghuysen had begun to challenge Dutch Reformed congregations in New Jersey, and the Tennents, William and his sons (particularly Gilbert), had done the same in some of the Presbyterian congregations in New Jersey, William even (1727) setting up a “Log College” (ultimately the future Princeton) in New Jersey to train new pastors imbued with the same evangelical spirit. By the 1730s something of the same order was developing in Massachusetts, as the young Jonathan Edwards was challenging his Congregationalist church members at Northampton with the same evangelical call to repentance. Soon all this began to attract additional members to his congregation, although (and most typically) this would come to upset many of the older and more “proper” members of his congregation, who felt that they needed no such religious repentance.

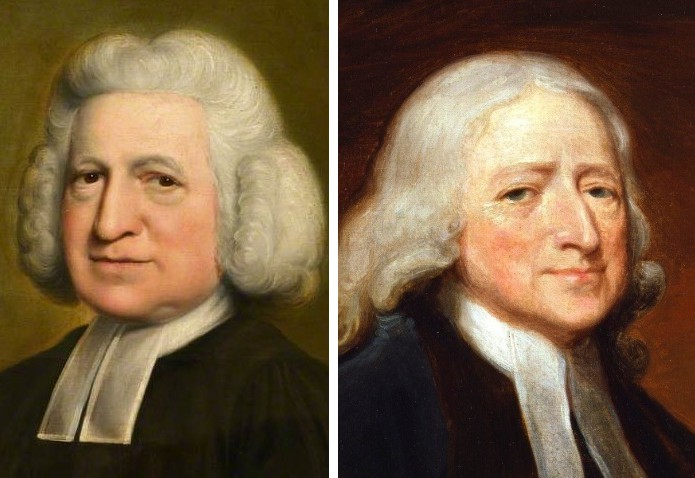

William Tennent Jonathan Edwards

The “Methodist” Wesley brothers

Meanwhile, back in England, something of the same order was taking place, thanks especially to the efforts of the Wesley brothers, John and Charles, who started things out at Oxford University as students there when they developed their own evangelical circle, scorned as “Methodists” because of the way their evangelicalism seemed to take on a precise form or “method.” Then they would attempt to expand their “mission” by heading to America (1735) in the hopes of being part of the Idealism that had just birthed the Georgia colony, although the venture ended up disappointingly, and the Wesleys headed back to England (1737). But the real fruit of the whole venture occurred during that trip to Georgia, on a ship including Moravians who showed John Wesley what real spiritual living looked like. Back in England he would continue his close relationship with the Moravians, and continue to develop as a changed man, even though the label “Methodist” would remain associated with his ministry. And England would come to experience its own wider spiritual “Awakening” under the guidance of John and his brother Charles (the latter a musician and very talented hymn writer), as the Wesleys even took to the streets and fields to do their evangelical ministry.

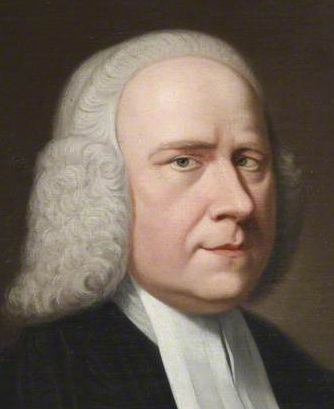

Charles and John Wesley

But one of their close Oxford associates, George Whitefield,* would return to America in 1740, supposedly to continue the charity work initiated by Wesley, that is, the starting up of a number of orphanages. Quite naturally, Whitefield, being an excellent speaker, was invited to explain the purpose of his ministry in various churches across the colonies. Those inviting him to speak to their congregations included Tennent in New Jersey and Edwards in Massachusetts. Soon he was speaking across the colonies, not just about orphanages but also about God’s call to his chosen people to come to full repentance, and a born-again Christian faith.

But one of their close Oxford associates, George Whitefield,* would return to America in 1740, supposedly to continue the charity work initiated by Wesley, that is, the starting up of a number of orphanages. Quite naturally, Whitefield, being an excellent speaker, was invited to explain the purpose of his ministry in various churches across the colonies. Those inviting him to speak to their congregations included Tennent in New Jersey and Edwards in Massachusetts. Soon he was speaking across the colonies, not just about orphanages but also about God’s call to his chosen people to come to full repentance, and a born-again Christian faith.

This truly began the explosive part of the “Great Awakening,” as now thousands of people wanted to hear Whitefield’s message, forcing him to have to take to open fields (like the Wesleys back in England) to do his preaching. And this now became the full-time pursuit of Whitefield, who would preach thousands of sermons over the many years that he did his evangelism across the colonies (all the way up until his death in 1770).

Of course this “style” was not well appreciated by a number of “proper” pastors and theologians, such as the Boston preacher Charles Chauncy, who considered both the open-field style and the call-to-repentance of “good” Christians to be in the worst of Christian taste. And there were also some who took up the evangelical call, and did indeed turn it into something more dramatic than real as far as authentic Christian ministry … such as the evangelist James Davenport, whose attacks on people who did not fully embrace his evangelical style was possibly itself shaped by personal insanity! There was a very interesting twist in the matter in the way that America’s well-recognized “man of reason,” Ben Franklin, took a distinct liking to Whitefield and his ministry, publishing some 40 of Whitefield’s sermons on the front page of Franklin’s newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette. And this was not just because Franklin was deeply impressed about how Whitefield’s voice reached thousands jammed into Philadelphia to hear Whitefield (that alone was indeed quite impressive). Franklin truly admired Whitefield. The two would in fact share an amazing friendship all the way up until Whitefield’s death.

Spiritual preparation for the struggle ahead

In any case, the Awakening did America an amazing amount of good. There were going to be years of deep trouble ahead, not yet foreseen by anyone, as the culprit, British King George III, had not yet appeared on the scene. Attempts to take their independent spirit away from them (inspired by George’s fear that such a spirit might infect British subjects at home in England) would soon be coming their way. And they could either submit to royal pressure (like peasants) or refuse to do so, and be treated as rebels, which historically would always go very poorly for such commoner rebels. In order not to become a part of that sad statistic, they would need some very special strength, strength to fight off whatever the King would throw at them, politically, militarily, spiritually. And that was what the “Great Awakening” was ultimately all about: getting them prepared spiritually to work together, to stand together, to fight together, as one, because they formed a single covenant society answerable only to their God in heaven, and not some far away member of the circle of English nobility. For certainly that spirit of unity under God was one of the results of the Great Awakening. As it reached north and south, it truly made the American colony seem to be one in nature, one in spirit, in the face of God’s call. And they would need that sense of unity badly, especially as not all Americans would think that rebelling against their king was a wise idea, even a good idea. Loyalists or “Tories” would find themselves quite opposed to such rebellion, a group particularly numerous in the South, where Anglican loyalties ran quite deep, and where the king was considered to be quite properly the head of the English church and society. Ah yes, but even there, because of the Great Awakening (especially Whitefield’s sermons), many of the humbler members of southern society would stand apart from that attitude typical of the southern gentry, breaking from their Anglican ties in becoming Presbyterians, and even more so in becoming “Baptists,” and thus quite different from the quite-Anglican southern gentry in their estimation of things. This would be another key reason that the Great Awakening was so important as to how America was to progress at that point as a “covenant nation.

Go on to the next section:

Independence … and the New Republic