CHAPTER ONE

WESTERN SOCIETY’S OWN MORAL-SPIRITUAL FOUNDATIONS

CHRISTIANITY AS FOUNDATIONAL

European society, from which America was birthed, understood itself to be quite Christian … at least from the point when the Roman Empire itself chose to become Christian in character. But that “Romanization” of Christianity in the 300s would, over time, take on many different forms, some of them even in deep opposition to the others. Indeed, even in America that same Christianity would come to be found in varying forms. More about that later.*

But Judaism itself was a religion of many varieties − although it had a single underlying theme which ran through its long history, a history well-recorded in the Jewish Torah or Testament. And that theme was that the God of the Heavens, who created all visible reality, but who lived above and beyond our realm of time and space, had created man and woman as Adam and Eve to be his audience, an audience very appreciative of the beauty of Creation itself. But he did not make these human originators out to be puppets, simply mouthing praise they were created to offer. He made them free agents, able by their own will to go at life this way − or not.

And the “or not” was a matter of whether they would use their reasoning skills to go higher in an effort of their own to connect with God … or whether they would use these same talents of human reason to go at life on their own, apart from God, on the basis of their own supposed intellectual skills. As the Torah or Jewish Bible puts the matter, would they follow God’s lead in discerning Good and Evil facing them in life … or would they eat of the fruit of the tree of just such knowledge to build their lives their own way? The latter choice, which had the appeal of making them seem to be something like gods themselves, was a very bad choice. As events were quick to prove, all this rational self-interest was a very deceptive matter.

Human logic, standing on its own feet, seemed to be so empowering. But human logic always finds itself operating from very narrow perspectives − which is what self-interest does.

And we just gave an example of how that worked. Ben Franklin was warning his fellow (Christian) delegates to the constitutional convention of how endless rounds of human reasoning had led them to miserable results − and how a prayerful turning to God for guidance was the only way out of this rational mess. Had they forgotten what they had previously done during the dark days of the rebellion against the English king − when all human strategies had little likelihood of success, when they were quite aware that a miracle from God would be the only thing that could save them? Once again, was it to be Human Reason or Divine Reason that would be their guides?

The lengthy history of the Jews − including their own Hebrew or Israelite ancestors − was always about this same problem. For instance, the Book of Judges is a recording of just such tragic rise and fall − rather repeatedly over the generations.

God finally gave up on the Israelites and let the cruel Assyrians march them off to captivity … and scatter them broadly across their empire, causing the Israelites to lose their social identities − in essence causing Israel to disappear. That was except, most importantly, the members of the southern tribe of Judah (the Jews), who had wisely stayed out of the international political foolishness in which the other Israelite tribes had believed themselves to be so clever. The Jews alone survived the disaster, to carry on the Israelite tradition.

The Babylonian transformation of Judaism

But here too, despite the warnings of the prophets for Judah to stay out of similar events, they themselves soon got caught up in a war, one between the Babylonians and Egyptians. And they too managed to get themselves − at least their leaders − marched off to captivity in Babylon (some in 597 BC and more some ten years later).

But the Babylonians allowed these captives to remain together as a community in Babylon. And this would have a miraculous impact on Judaism itself.

Understanding that their god YHWH* was the only God. First of all, these Jews had to deal with the question of their own defeat. Was the Babylonian God Marduk more powerful than their God YHWH? But they began to realize that there was actually only one supreme God as Creator and Overseer of the universe, and thus YHWH had to be as much a God for the Babylonians as he was for them.

The importance of being a covenant people. And as for their captivity in Babylon, there was certainly some kind of lesson involved that they were obliged to understand and accept … because even in captivity, they were still his covenant people. Especially in such captivity they were to see themselves as his covenant people − covenanted with God, the only God, to be a “City on a Hill,” a “Light to the Nations” … even to the Babylonians!

Their historical narrative – not their Temple’s altar – as the center of their worship. Also, as prisoners in Babylon, these Jews were obviously unable to conduct normal Jewish worship at a temple. Indeed, the Babylonians had even destroyed their temple located back in Jerusalem. But worship at an altar in a political-centering temple conducted by a select group of priests was normally the foundation of the social-moral identity of any and all societies back then. And therefore, no longer permitted to conduct such worship in Babylon, the Jews feared the loss of their identity as a distinct people.

But most amazingly, they got to the task of bringing together as a distinct social narrative their ancient stories, stories of their ancestors Abraham, Moses, David, and others – stories good and bad, but always very instructive. And in doing so, they assembled that narrative as their written Torah or Bible (what Christians term as the “Old Testament”).

And they would now simply meet regularly on a weekly basis on the day of Shabbat (the Sabbath), where teachers (rabbis) would lead those gathered there in reviewing selections of that Biblical narrative, offering on the basis of that narrative precise instructions as to how they were to live, live as they felt that God himself had appointed them to live, even in a foreign land.

Thus it was that this narrative itself was able to define them as a distinct people. They discovered that they needed no temple priests and temple altars to define them – as long as they had that written narrative to identify them as God’s special people, as that “chosen” people.

That historical narrative defines them … wherever they chose to live on this planet. Eventually (beginning in 521 BC) with Babylon’s defeat at the hands of the Persians, the Jews would be given permission to leave Babylon and return to their original homeland of Judea, and rebuild their temple and put their priests back to work. But most of the Jewish community was quite content to remain in Babylon (Babylon now a part of Persia), where they continued to develop as a Jewish society. At the same time many saw good reasons to move to Egypt, and there also conduct their social life in that same Babylonian way, self-identified merely by that very special narrative of theirs examined in part at their local weekly gatherings. And with the rise of the Roman Empire, they would find themselves also located in an even broader world, because they could take that narrative with them – and continue to be God’s special people, no matter where they lived. This was most exceptional.

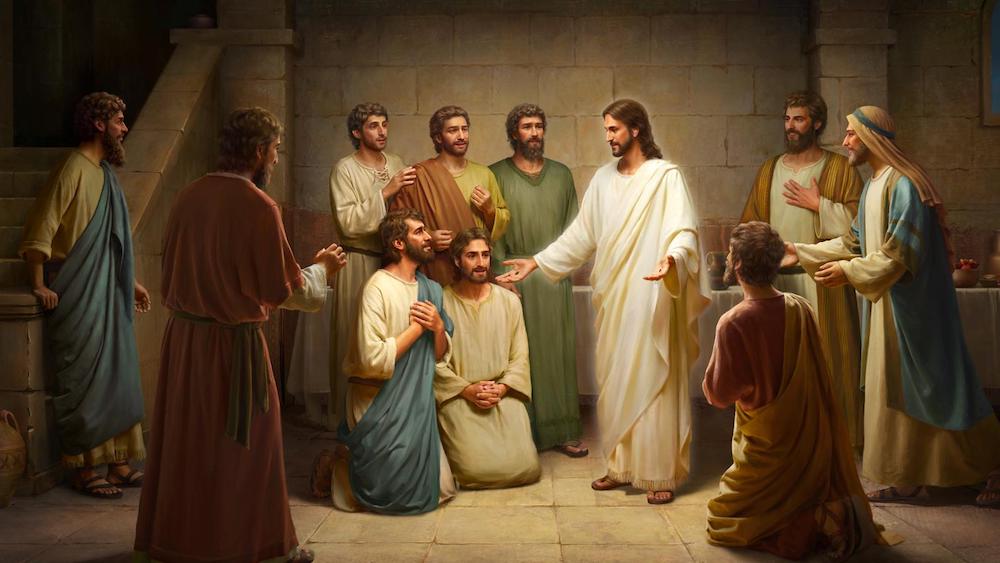

Jesus illustrates God’s compassion. Jesus of Nazareth was not exactly what the Jewish world at the time (four centuries after the Jewish “return” to Judea) was looking for as a deliverer or Anointed One (Messiah). The Jewish community was hoping for the arrival of some kind of a new King David – an individual blessed with awesome political and military powers able to restore the Jewish world (still identified as Israel) from not only Greco-Roman bondage, but even once again to greatness.

In so many ways, as their Messiah or “Christ” (Greek), Jesus was quite the opposite. Jesus was soon understood by many to be a prophet, a teacher, the very voice of God − not a warrior. He made it clear that his job was to bring God’s people back to God in obedient service … not to some kind of earthly glory. They were to rise above their natural tendency to want to bring things under their own personal and social control, rather than to rely on God’s guidance and protection – the problem that the Jewish community (and all humankind for that matter) had always faced.

As far as the natural human hunger for personal and social glory went, Jesus chose to work with the lowly, the commoners, even the sinners … demonstrating that God was interested in spiritual reunion with all (even sinners). God was not impressed with social or even religious prestige. Of the latter, there was plenty … scribes, Pharisees and other religious notables – individuals that usually found themselves greatly annoyed by what Jesus represented.

Jesus’s miraculous power. Even more troubling for the “intellectually comfortable” of those days, was the strange powers that accompanied Jesus’s ministry: the spectacular healings of the sick, the disabled, the blind … even the dead brought back to life. So bizarre was all this that the “realists” (most of the intellectual and religious dignitaries of the day) even came to deny what they had witnessed with their own eyes, so unbelievable (given their self-imposed belief limitations) it all was. But multitudes knew it all to be real – because they had indeed witnessed personally that power.

For Jesus, this was simply the proof of the very presence of God in all his loving power – a power available to all who believed in him … regardless of their religious credentials. Jesus even seemed to have a special interest in bringing that loving faith to the despised Samaritans! And also most amazingly, he also empowered his simple disciples (not religious scholars or priestly authorities but ordinary fishermen and other common laborers) to follow him down this miraculous path of faith in God − as also their “own Heavenly Father.”

For the hurting lower members of society, Jesus’s ministry had a very strong appeal. But most unsurprisingly, to those of the upper ranks of society, empowered to preside over others − and supposedly the events in their social lives − Jesus’s ministry was greatly unappreciated. His teachings undercut not only their social importance, they also made the highly respected religious credentials of the social elite seem to be rather insignificant in the greater scheme of things.

The miraculous irony of Jesus’s death on a Roman cross. And people of power do not like to be undercut by others. Thus the Jewish religious leaders got the Roman governor to do what they themselves were forbidden to do … kill the “charlatan” Jesus. And so on the grounds of a great lie, Jesus was put to death most humiliatingly − and most cruelly − on a Roman cross.

But also, and most ironically, Jesus’s death on the Roman cross proved to be the removal of the last barrier to anyone’s true spiritual freedom − allowing a person to leave the logic of the world behind and reach upward to God. Human sin, which darkens the hearts of any human, was − in the eyes of God himself − now washed clean by Jesus’s self-sacrifice on that cross. Consequently, in a person’s willingness to receive in full faith this sacrificial gift, they were now, in God’s eyes, dead to the former person they were, and now ready to live a new life in full faith in God.

Jesus’s resurrection from the dead. And to prove the power of this event, Jesus was even brought back from his death to spend a short period of time with his followers, to make clear to them the point of his miraculous ministry. By doing this, he was offering proof that everything by which he had presented the presence of God in all his loving power was very, very real.

And then he left their company to take up again his heavenly throne.

Christianity’s moral-spiritual development

His disciples continue his ministry. Something of that same divine spirit (identified as simply the Holy Spirit) now filled the hearts and souls of his followers … now sent out as “apostles” to spread the “Good News” (or Gospel) of what God had just shown humanity of his own divine nature or being – in the form of his Son, Jesus. And these apostles even found their own ministries equipped with the same spiritual powers Jesus had demonstrated – healings, revivals of the dead … and just in general strange supporting events that had no natural or material cause to explain their occurrences. Thus it was that, with the enormous help of God’s Holy Spirit, the disciples were able to spread the movement quite readily … even across the reach of the Roman Empire.

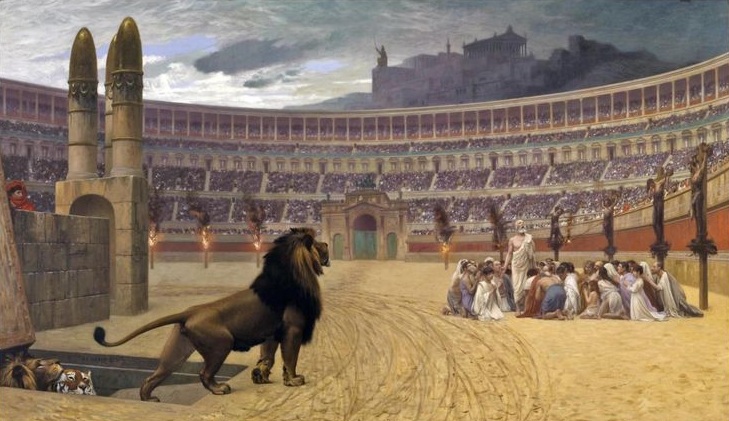

The Christian “church” is born. Members of the Christian faith would follow the Jewish pattern of keeping their community intact by meeting regularly on a weekly basis (eventually the Lord’s Day or Sunday) to go over their common Christian narrative … presented Jewish style as “sermons” by interpreters of the collected Christian writings or Scripture, such individuals serving as “pastors” of their “flocks” of the faithful. Much of this had to be done in secret, because the faith was most unwanted not only by the more orthodox Jewish community but even by the Roman authorities – especially after the Christians made it quite clear that they would bow in worship only to God … not to some Roman emperor.

Most unsurprisingly, Roman persecution of Christians became quite brutal. But the incredible ability of persecuted Christians to meet most serenely the ugly public displays of their deaths had a deep impact on the consciences of ordinary Roman citizens – and even over time on those of the more aristocratic patrician classes. Somehow all this persecution did was to put Christianity in an even greater light – given the moral-spiritual darkness that descended on Roman society as the 200s moved along.

Emperor Constantine accepts the Christian faith. Then a grand miracle hit both Rome and the Christian faith … when in 312, in following instructions offered in a dream to have his soldiers go into battle with the Chi-Rho symbols of Christ painted on their shields, Constantine and his troops were able to defeat a contending Roman army twice their size, bringing Constantine to power as the Western Emperor. The following year, Constantine and his ally Licinius* (Eastern Emperor) issued the Edict of Milan, ending further persecution of Christianity.

Emperor Constantine accepts the Christian faith. Then a grand miracle hit both Rome and the Christian faith … when in 312, in following instructions offered in a dream to have his soldiers go into battle with the Chi-Rho symbols of Christ painted on their shields, Constantine and his troops were able to defeat a contending Roman army twice their size, bringing Constantine to power as the Western Emperor. The following year, Constantine and his ally Licinius* (Eastern Emperor) issued the Edict of Milan, ending further persecution of Christianity.

Trinitarianism versus Unitarianism. How much a Christian Constantine happened to be at this point is hard to say. His wife was definitely a Christian. And he certainly favored the faith – seeing to it that various councils of Christian bishops were held in order to clarify exactly what the Christian faith consisted of. Most importantly, through his imperial support, the Council of Nicaea was called in 325 to settle the matter dividing Rome’s new Christianity into two contending groups, the Unitarians versus the Trinitarians. He came down strongly on the side of the Trinitarians, this group seeing Jesus’s ministry as being more than just offering the world another formula of “good works,” or religious works designed to please God and thus earn people the right to a heavenly reward at their death.

The Trinitarianism that he and other church leaders supported is much less “logical” in simple terms than Unitarianism – but totally Biblical. For instance, the Gospel of John opens with the declaration that Jesus was in fact the Logos* incarnate. Jesus was God come to earth in the form of a man … and not just a prophet or very good man who at his death earned his place of prominence in heaven because of his awesome works on earth – as Unitarians believe. As Trinitarians, the gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) and Paul’s letters explained Jesus to be God’s own self-offered blood sacrifice, a divine gift on that Roman cross designed to be a sacrificial substitute for human sin – all human sin, then and forever. But that divine atonement for sin was valid for someone only if the believer truly gave such self-judgment over to God through pure and simple faith … not through any religious works of theirs. And the idea that God continues to be among us in yet a new form as the empowering Holy Spirit was another key element in the Trinitarian understanding of how God’s Creation was designed to work. In short, to the Trinitarian, God has revealed himself to us in three distinct but intimately related forms: the “Trinity” of Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Sadly, Unitarianism versus Trinitarianism remained an ongoing works-versus-faith religious issue, an issue that never seemed to go away over the years … despite the official church’s early support of Trinitarianism.

The “Romanization” of Christianity. Of course Constantine’s desire to see the Christian faith put on rational, even legal, grounds was itself quite “Roman.” But this was only the beginning of a process by which Christianity quickly evolved from a deeply personal relationship with the Lord of the universe to a relationship with larger life through a process managed by a huge religious organization … something more typical of traditional religions. In this development, individuals were now answerable to local priests, local priests answerable to regional bishops, regional bishops answerable to one of the five major archbishops presiding over huge sections of the Roman Empire, and the whole process answerable to Jesus … and the emperor. Then by the time (the late 300s) that Emperor Theodosius made Christianity Rome’s sole religion – banning all previous forms of pagan worship – Jesus himself appeared largely as a colleague of the emperor, confirming imperial rule and helping the emperor govern Rome’s massive church bureaucracy.

In all this, Jesus most sadly became quite distant as a personal guide and savior to the average Christian. Consequently, personal divine support was sought elsewhere. Previously, particular pagan deities reputed to have special powers in particular areas of life (health at home, safety in travel, success in romance, etc.) were looked to in prayer for personal support. But with such pagan worship now banned, Romans soon found it easy to look in the same way to various Christian saints, themselves reputed to have such particular powers. This was not exactly Biblical Christianity. But the Christian powers-that-be decided that this would be acceptable practice within Roman-styled Christianity.

Likewise, Earth Mother – previously a highly popular and quite warm female deity (Isis, Demeter, Astarte, Aphrodite, etc.), but now also outlawed by those same Christian authorities – soon found an easy replacement in Mary, mother of Jesus. However, and most ironically, other than being responsible for Jesus’s birth, Mary actually played only a very minor role in Biblical Christianity. But over time, in Roman Christianity, she became increasingly important as someone (something of an Earth-Mother substitute) to be prayed to for divine assistance … even by the decision of the Council of Ephesus in 431 to be recognized not merely as Christotokos – Mother of Christ – but now even Theotokos – Mother of God. Soon churches were being dedicated to her – not to Jesus.

In all of this, both Western Christianity (Roman Catholicism) and Eastern Christianity (Eastern Orthodoxy) found their very strong religious foundations.

CHRISTIANITY STRUGGLES TO MAINTAIN ITSELF IN THE WEST

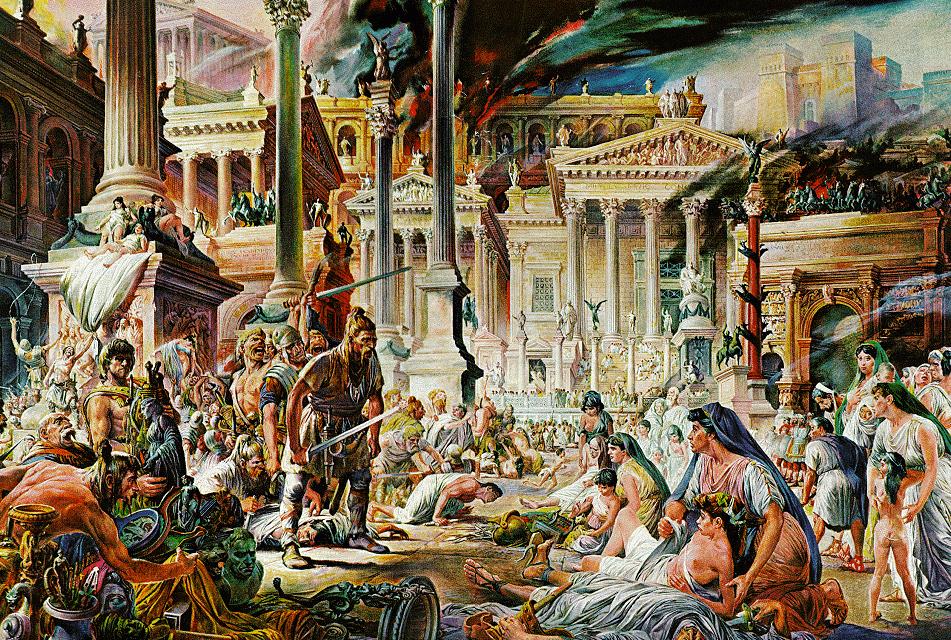

A long “Dark Age” descends upon the West. The next thousand years would be very tough for the West. Germanic tribes pressed in on a weakening Roman Empire from the North. And Persians were doing the same in the East. The Eastern or Byzantine half of the Empire – with its new capital at Constantinople – protected itself by diverting the Germanic tribes westward … bringing the old imperial capital at Rome itself to full ruin when Alaric and his Visigoths sacked and burned the city in 410.

Then the Western Roman Empire simply was divided up into a number of Germanic kingdoms: Visigoths, Franks, Wendels, Anglo-Saxons, Lombards, etc., each taking a piece of Rome’s West.

In that Western world, about the only thing of any political-social importance to survive was the Christian Church, still headed by a line of most capable bishops of Rome or “Popes.” Very significant to the survival of the Church was also how also a simple missionary Patrick was able to bring Ireland to the Christian faith (Trinitarian) in the 400s … and then leave a legacy of strong Irish missionaries to head to Britain and the European continent in the 500s and 600s in order to bring the Germanic tribes (already mostly Unitarian Christian) to full Trinitarian Christian faith. Thus the Roman Christian legacy was preserved – although the economic and social primitiveness of the Germanic societies remained fairly unchanged.

Then in the late 700s the Frankish king Charlemagne was able (with strong political-moral support from the Roman Pope) to conquer most of the neighboring Germanic tribes – thus bringing Western Europe (the continent north of Spain, including Italy and the Germanic East) to political unity. For a bit, (the early 800s) it appeared that his huge empire was about to begin something of a social-cultural revival as well. But when his new empire was divided up among his grandsons (mid-800s), that hope ended. But it did provide the beginning of the idea of Europe having distinct French, Italian, and German societies … each headed by a king or monarch of some type and supported by a hierarchical feudal system of governance.

Then in the late 700s the Frankish king Charlemagne was able (with strong political-moral support from the Roman Pope) to conquer most of the neighboring Germanic tribes – thus bringing Western Europe (the continent north of Spain, including Italy and the Germanic East) to political unity. For a bit, (the early 800s) it appeared that his huge empire was about to begin something of a social-cultural revival as well. But when his new empire was divided up among his grandsons (mid-800s), that hope ended. But it did provide the beginning of the idea of Europe having distinct French, Italian, and German societies … each headed by a king or monarch of some type and supported by a hierarchical feudal system of governance.

Europe’s feudal system. Charlemagne, as “Emperor” had originally established the feudal system to govern this vast empire, with his appointment of subordinates – usually identified as “barons” or “dukes” – to rule huge sections of his realm … of course in the name of and supposedly in full support of the emperor. But even these sections of land were so vast that they were themselves subdivided into smaller political units, overseen by “counts.” Supposedly this was all just a simple way of making sure that the emperor’s governance was carried out in an orderly fashion across the empire.

But with time, there was a tendency for barons and counts to want to see these appointments passed on to their own offspring, families thus setting themselves up as a privileged ruling class … each family located in a system that assigned levels of importance or status to them on the basis of the amount of land (and number of people under their authority) that the family controlled.

As for the commoners in this system, not part of the ruling program at all, they were raised to understand their place in the system simply as farmers and workers − not even awarded the smaller social privilege as soldiers or “knights” in service to the local lord. They had no say in choosing who it was that would govern them, that being a matter belonging strictly to the ruling class. And for the ruling class, that was a matter of how wealth, power and family connections flowed across that ruling class. Thus peasants could wake up one day to find that they had a new aristocrat governing them, through death or marriage, not through any action on the part of the commoners themselves.

This system was to remain in place in Europe for a thousand years … and be replaced only gradually by the development of Europe’s urban societies − with some of the rural lands remaining under the feudal system even all the way to the end of 1800s. The urban societies, however, would come to operate quite differently. But more about that later.

More challenges. But in the meantime, a new challenge to the Christian West had come in the form of Islam – something of an Arab religious derivative from Christian Unitarianism. It was Islam that finally brought Eastern or Byzantine Rome to ruin (early 600s) … with Arab conquerors heading west across north Africa and on into Spain. There in Spain, Islam would install itself strongly over the next centuries – not even Charlemagne able to restore the area to Christian rule. But at least Islam could reach no deeper than Spain into the West.

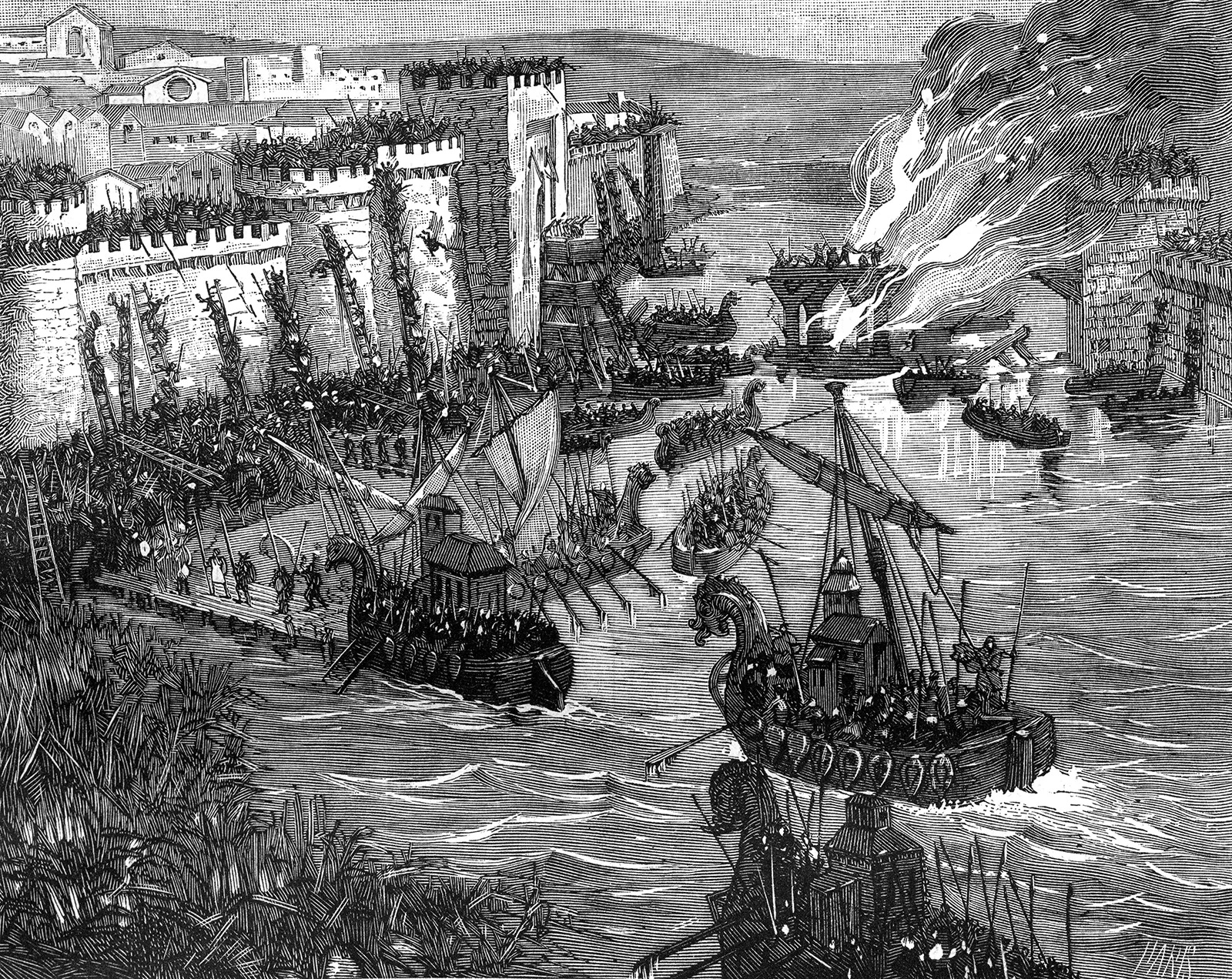

But then a new danger hit the West, adding to the inability of the West to get back up and running again – when Vikings or Northmen (“Normans”) came crashing down on the West, including now the British Isles as well. For several centuries (800s-1000s) the raids continued.

But eventually even these Norman raiders settled into Western society and took up its “Christian” ways – in the process actually giving the West a bit of new military vigor. They also gave Britain a new Latin-speaking (French) ruling class, Norman rulers now (after 1066) lording it over the still Germanic-speaking Anglo-Saxons (English commoners). England thus would become something of a Latin-Germanic blend – but a blend distinguished by a sharply divided class system. But the Norman monarchy and the highly supportive English Church would do what it could to keep England functioning as a single society.

The beginnings of a Western revival. Then things would take a strange turn … when the hard-pressed Byzantine Christian East pleaded for help from the Christian West in fending off the constant pressure coming from the world of Islam. And at the end of the 1000s, the West answered this appeal with a call for a “crusade” against the Muslim East – one designed to bring the area back under the cross of Christ. Whether this had anything to do with Christ’s original ministry or not was beside the point. This was about conquest, pure and simple.

And for the better part of a century (1100s) it looked as if all this was fairly successful. But the Muslims were in no mood to call it quits, and under Saladin, reversed matters in the area in favor of the Muslims in the later part of the 1100s. But Christian Europe was not itself willing to call it quits, and organized yet more such crusades … involving even European monarchs in the process. Ultimately, however, the Muslims were able to hold their ground, and the crusading spirit began to wane in the 1200s.

The socio-economic impact on the West … most notably Italy. But something else was changing this East-West dynamic at the time. First of all, it had come as something of a shock to Westerners to see how very advanced Muslim culture was – in comparison to the more boorish style of Western society. Secondly, the flow of money grew in importance as a factor in all this dynamic, crusaders bringing back the plundered wealth of the East, enriching themselves in the process. But cities such as Venice and Genoa also grew rich from all this, providing sea passage from their ports all the way to the East … receiving payment for that privilege by the crusaders themselves of course. And both Northern Italian cities grew quite rich from the process, Venice even setting up something of a maritime empire of its own across the Eastern Mediterranean.

Italy’s Florence now also jumped into the economic scene … not as a naval power but as a powerful banking center … with Florentine banking facilities located around the Mediterranean − where letters of credit rather than cash shipments made the exchange of goods so much simpler and more profitable.

THE RENAISSANCE

Something deeply social and cultural was beginning to develop in Europe during the 1200s and 1300s … a lot of that because of those contacts with the Muslim world. For instance, in discovering the Arab’s pointed arch, churches (or at least expensive cathedrals) could be built to towering heights, and yet be able to place delicate stained glass windows in the walls – somethings that began to hit Western architecture big even as early as the 1100s. And the discovery of Arabic numerals and Arabic Al-Jabr (algebra) revolutionized Western mathematics around the same time.

Something deeply social and cultural was beginning to develop in Europe during the 1200s and 1300s … a lot of that because of those contacts with the Muslim world. For instance, in discovering the Arab’s pointed arch, churches (or at least expensive cathedrals) could be built to towering heights, and yet be able to place delicate stained glass windows in the walls – somethings that began to hit Western architecture big even as early as the 1100s. And the discovery of Arabic numerals and Arabic Al-Jabr (algebra) revolutionized Western mathematics around the same time.

But Westerners themselves added to the rising world of discovery … with the invention of the mechanical clock in Italy during the 1300s (not terribly accurate … but a good beginning). Likewise, Italians are reputed to have quite independently in the 1300s (the Chinese had done so much earlier) discovered the use of lodestone … to give themselves a compass to direct themselves on the high seas.

But certainly most revolutionary was the invention of the moveable-type printing press by the German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1440). This would not only revolutionize the world of written information with his use of his method to begin in 1452 the process of printing Latin Bibles, this would have a tremendous impact on Christianity itself.

And a virtual revolution in art would develop during this same time period (the 1400s) … certainly in big part due to some of Florence’s leading families (most notably the Medicis), graciously using their wealth to become major art patrons … supporting greatly the work of a widening realm of very talented artists and architects.

Of course a great deal of this art was religious in character − portraits of Mary, Jesus and the saints, for instance. But also added to that were “Humanist” works … portraits and sculptures of European notables, and paintings of everyday life, of historical events, and even of mythical tales.

Not all of this development took place in Italy. Similar economic development also took place in coastal Northern Europe, where wool and woolen cloth were in high demand in the Middle East … as well as lumber, dried fish, and numerous other products that found eager markets in the Arab world. Thus the coastal cities of Flanders (Ghent, Bruges, Antwerp) grew quite wealthy from their trade with the East, as did London (access to the high seas via the Thames River). And even German cities way to the North (members of the Hanseatic League, stretching across the Baltic coast) got in on the act.

And of course along with this went developments in the world of art, learning, and general cultural development. Excelling at this was particularly the coastal region of Flanders − whose cities soon reached the economic and cultural level of Italy’s grand cities.

Europe’s new global reach. Back at the beginning of the 1300s, Marco Polo had shocked Europe with his writings narrating his 24-year experience in the Far East … and what he had discovered about Chinese society and culture (17 of those years spent there in service to the Chinese emperor) … and other Eastern cultures in the process. With that revealing of the splendor of the Far East, efforts now got underway to reach east even beyond the Muslim world.

Getting a jump on things were the Portuguese, who undertook in the 1400s to get to the East by swinging south around Africa and then heading East – to reach the wealth of India.

But not to be outdone, the Spanish monarchy (notably Queen Isabella) took up the offer of the Genoese explorer Columbus to reach the fabulous East by taking the alternate route of heading west across the Atlantic (the West well aware of the global nature of the earth at this point … though clearly not yet its size!). Thus in 1492 (just as the Spanish were also completing the task of driving the last of the Muslims out of the Spanish peninsula!) Columbus finally discovered what he believed to be India … and thus the people living there, “Indians” − a name that Europeans would forever assign to the tribesmen living in the Western Hemisphere, despite the fact that these people were hardly from India!

Spanish grandeur (the 1500s). Further Spanish exploration soon revealed not only the extensive nature of the land Columbus had bumped into … but its vast wealth. Two Spanish conquistadores (conquerors) and their troops, Cortez in Mexico and Pizarro in Peru, were able in the early 1500s to bring back to Spain mind-boggling amounts of gold, stolen from the native societies they had conquered. This made Spain vastly rich. And benefiting most from this was Spain’s powerful ruling family, the Habsburgs, Charles* (ruling 1516-1556) and his son Philip (1556-1598). Under their rule, Spain became the most powerful society in all of Europe.

The only problem with all this wealth however was that the Spanish did not understand the importance of actually investing this wealth in enterprises that would continue to generate wealth for them. Instead, they simply spent that wealth on this and that item, especially property, fancy goods and events, and the social status that went with it. And when that gold plunder from America began to run out (silver would provide a smaller alternative) so did Spain’s wealth – and power (the 1600s).

THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION

For centuries, the Western Church– in all its power – was unquestionably governed by the Pope of Rome, himself elected by top church officials. But Secular powers, princes, kings, and even the Holy Roman Emperor, had the natural tendency to want to challenge such power – say, for instance, over the matter of who exactly, the Pope or the regional prince, got to choose regional church leaders (the “investiture controversy”). With the arrival of the 1300s, increasing Secular culture, and its accompanying social power, moved matters in favor of the princes. For instance, from 1309 to 1376, the papacy was moved from Rome to Avignon, France – the pope to be “protected” there by the French monarchy (the popes’ “Babylonian Captivity”). This was a huge embarrassment to the official Church. Eventually the papacy was returned to Rome … only to find a number of contenders there also posing as popes. Finally, in the early 1400s, a church council (the Council of Constance) attempted to bring things back to order … even “reform” the Church somewhat. But reform was ultimately not what most church officials wanted.

Early efforts at Biblical reform. Then just to make things more confusing, around the same time, certain religious scholars began to take an interest in the matter of exactly how much the Church had wandered from its early religious foundations, foundations readily discoverable in Christian Scripture itself. But taking on just such a venture was not well appreciated by Church authorities.

Worse, Oxford University scholar John Wycliffe not only publicly attacked the Church for its greed – and the way it had wandered from original Biblical standards – he even produced an English translation of the Bible, to make it more easily available to ordinary Englishmen. For this he was kicked out of Oxford in 1381. But a group of Christians, contemptuously termed “Lollards” took up his cause. But a Peasants’ Revolt that broke out at the same time (due largely to the economic impact of the Black Death, that had killed half of Europe’s population in the mid-1300s) became the excuse for England’s authorities to come down hard on Wycliffe and his reform movement.

Worse, Oxford University scholar John Wycliffe not only publicly attacked the Church for its greed – and the way it had wandered from original Biblical standards – he even produced an English translation of the Bible, to make it more easily available to ordinary Englishmen. For this he was kicked out of Oxford in 1381. But a group of Christians, contemptuously termed “Lollards” took up his cause. But a Peasants’ Revolt that broke out at the same time (due largely to the economic impact of the Black Death, that had killed half of Europe’s population in the mid-1300s) became the excuse for England’s authorities to come down hard on Wycliffe and his reform movement.

But a Czech (or “Bohemian”) scholar at the University of Prague, Jan Hus, took up Wycliffe’s cause at the end of that century, translating the Bible into Czech and calling for church reform. When Hus’s reform movement quickly gathered support in Bohemia, most unsurprisingly the Church and political authorities became greatly alarmed – as this put the reform movement much closer to Rome itself. Supposedly simply to explain his reform movement, he was called to the Council of Constance (1414) – under the emperor’s promise of safe conduct. But they were not interested in his explanations, and simply had him arrested, and put to death by fire (1415). So much for the emperor’s promises! At the same time, the already deceased Wycliffe was declared a heretic by the Council, his bones dug up, and his ashes scattered.

The Church would tolerate no such nonsense that these two reform figures represented. And so the reform movement died away – until it resurfaced a whole century later.

Luther. In the early 1500s, the Augustinian monk and German Biblical scholar Martin Luther found himself deeply grieved by the corruption that was very obvious in the Church (a personal trip to Rome making such corruption quite evident to him). The Church was selling “indulgences” that supposedly had the power to speed a sinner through the waiting period (Purgatory) that awaited them at death … before they could be cleared of their sins and finally be admitted into heaven. This was simply a scheme of the Pope to pay for his elaborate Vatican headquarters he was building in Rome … and had absolutely no Biblical basis. Finally (1517), an upset Luther challenged the Church to defend itself on 95 points … posted publicly on the door of the Wittenberg Chapel. Luther’s reform movement was now underway.

Luther. In the early 1500s, the Augustinian monk and German Biblical scholar Martin Luther found himself deeply grieved by the corruption that was very obvious in the Church (a personal trip to Rome making such corruption quite evident to him). The Church was selling “indulgences” that supposedly had the power to speed a sinner through the waiting period (Purgatory) that awaited them at death … before they could be cleared of their sins and finally be admitted into heaven. This was simply a scheme of the Pope to pay for his elaborate Vatican headquarters he was building in Rome … and had absolutely no Biblical basis. Finally (1517), an upset Luther challenged the Church to defend itself on 95 points … posted publicly on the door of the Wittenberg Chapel. Luther’s reform movement was now underway.

In 1521 Luther was called by the newly elected Holy Roman Emperor Charles of Habsburg to an Imperial Council (Diet) being held at Worms, Germany … for Luther to account for his demands for Christian reform. And this Luther did – under a highly suspicious promise of safe conduct by the emperor.

He of course failed to convince the emperor of the needs for such reform … and was pressured to admit his failures – which he refused to do. Then he got away before he could be apprehended by the local authorities, and was whisked away to protection by a sympathetic German nobleman, Frederick III of Saxony. And hiding from the emperor at Frederick’s Wartburg Castle, Luther not only set himself quickly to the task of translating the Bible into German, he continued to issue commentaries urging Biblical reform, his commentaries read widely.

Unfortunately, thousands of German farmers or peasants misunderstood Luther’s call for Biblical reform, and supposed that this also meant reform of the social-political feudal system they lived under, in which all land was owned by a small group of privileged nobility, and they, the peasants, lived on and worked the land only at the tolerance of those aristocratic landowners. When the peasants rose up in rebellion not only against the Church but also against this nobility, Luther came down hard against the peasants, even when thousands of these peasants were killed in the process of putting down their revolt (1524-1525). No, Luther was unwilling to go any further than just theological reform. Political-social reform he had no use for.

The Catholic counter-reformation. A key step of the Church in the face of Luther’s ongoing protests was to undertake its own religious counter-initiative in creating the Jesuit Order: monks dedicated as teachers and missionaries in personal service to the head of the Church, the pope. They would work hard to keep the Church’s position strong in Europe, and also advance its position abroad. Indeed, they would send numerous Jesuit missionaries to Japan and the Philippines in East Asia, but also to Canada and the Mississippi valley in North America.

The Church would also meet in Trent (1545-1563) to go over claims of the Lutheran protesters or “Protestants.” But aside from some cleaning up of the moral corruption in high places, the Council of Trent did not change any of the religious traditions of the Roman Catholic Church.

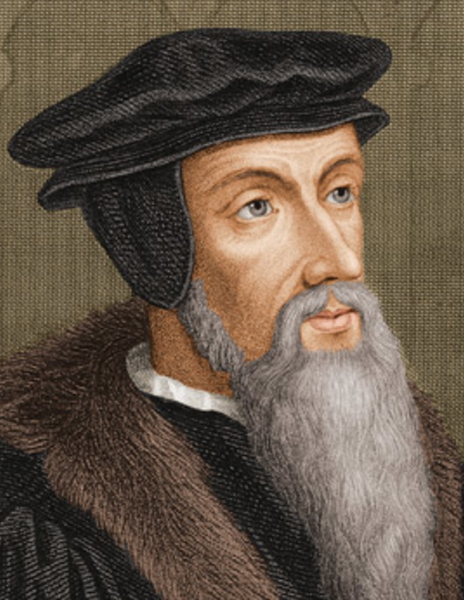

Calvin. But there was another individual who would have a tremendous impact on the “Protestant” Reform Movement – in fact, someone whose legacy would shape deeply the moral-spiritual foundations that New England’s Puritan America would be built on – the Frenchman John Calvin. In 1536 the lawyer in him made him feel compelled to write The Institutes of the Christian Religion,* a strong defense of the Protestant Reform Movement, which was dedicated to getting Christian society to live as close as possible to the way the Christian Bible described the moral-spiritual nature and social character of 1st century or “original” Christianity. This reform movement had even reached France at this point, and Calvin dedicated his Institutes to the French king, Francis I, in the hope of gaining his approval and support.

Calvin. But there was another individual who would have a tremendous impact on the “Protestant” Reform Movement – in fact, someone whose legacy would shape deeply the moral-spiritual foundations that New England’s Puritan America would be built on – the Frenchman John Calvin. In 1536 the lawyer in him made him feel compelled to write The Institutes of the Christian Religion,* a strong defense of the Protestant Reform Movement, which was dedicated to getting Christian society to live as close as possible to the way the Christian Bible described the moral-spiritual nature and social character of 1st century or “original” Christianity. This reform movement had even reached France at this point, and Calvin dedicated his Institutes to the French king, Francis I, in the hope of gaining his approval and support.

But instead, Calvin got quite the opposite result, and immediately had to flee France. On his way to Germany, Calvin stopped in Switzerland, and was urged by a local leader aware of his work to come to Geneva and help the Swiss Reform Movement already underway there − thanks to the Zurich reformer, Ulrich Zwingli (killed in battle in 1531). This Calvin did … until his reforms quickly irritated the town’s leaders and Calvin thus felt compelled to continue on to Germany (1538).

But things soon turned bad in Geneva. And in 1541 he was urged to return to Geneva, under his own terms. He agreed. And so things went.

And so also Geneva became a major Reform center. Indeed, under Calvin it became the center of what would become widespread “Calvinist” reforms, reforms which reached Scotland as Presbyterian Protestantism, England as Puritan Protestantism, France as Huguenot Protestantism, Germany and the Netherlands as German and Dutch Reformed Protestantism. Indeed, it reached even Poland and Spain, although the Catholic Counter-Reformation would succeed in eliminating such Protestant Reform in those particular countries.

Like Luther, Calvin got to the business of having the Bible translated into various European languages, including a well-loved English-language Geneva Bible. But Calvin went much further than Luther, in undertaking social-political reform as well as just theological reform.

A big part of this Calvin dynamic was because Calvinism touched strongly the hearts of a more urbanized Europe, where feudalism had long lost its hold. Urbanites were economically much more self-sufficient, even entrepreneurial in the way they went at life. They were also more “democratic,” in that city officials were elected to office by various voting groups, and did not just inherit such political positioning by way of special birthrights. There was therefore a greater sense of equality, at least with respect to potential in life. Opportunities were more open to anyone willing to take a try at things.

And as Calvinism stressed the idea of the basic equality of all Christian believers, because in God’s eyes they were indeed all equal, this really struck an approving note in fast-rising urban Europe.

Thus it was that fellow reformers flocked to Geneva to see firsthand what was going on there. And that would include, importantly for our story, a large number of English Puritans, eager to take back to England what they had discovered in Geneva.

Go on to the next section:

America’s Colonial Foundations